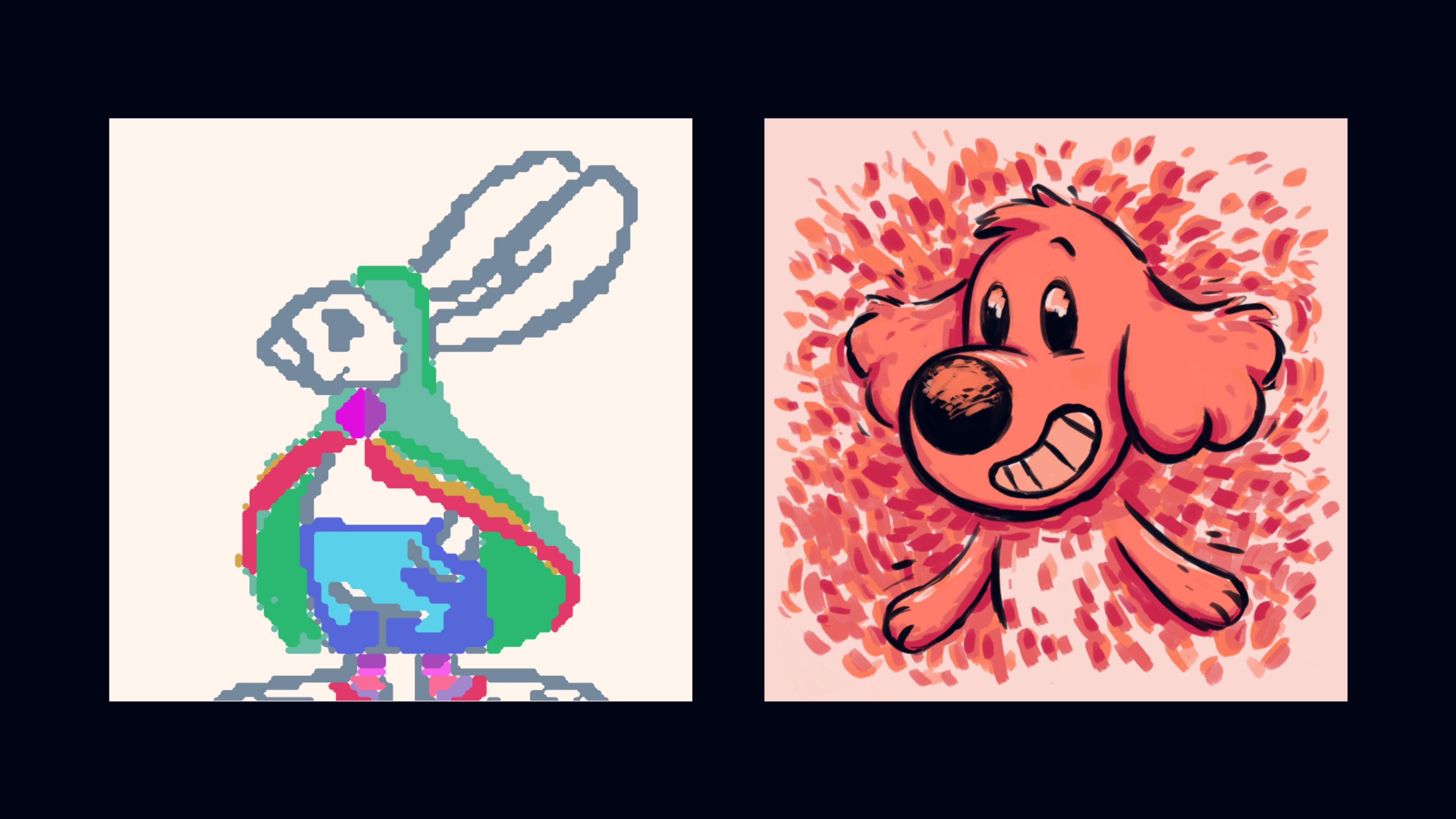

Despite its big, chunky picture book veneer, this top-down adventure game strikes hard at what it actually means to be creative, celebrating its joyous and fulfilling highs while also tackling its (sometimes literally) monstrous lows, including imposter syndrome, burn-out, depression and more. It’s very much a story first, game second kind of tale, but as with Wandersong before it, its winsome cast, sensitive story-telling and infectious soundtrack go a long way in papering over its somewhat limited mechanical toolset. At the risk of sounding like a big clanging cliche, it’s very artfully done. Chicory wears its inspirations more clearly than Wandersong. Its top-down, screen-by-screen world design is classic handheld Zelda, while the ability to paint directly onto your surroundings conjures images of Okami. Later, your traversal skills come straight out of Splatoon’s playbook, letting you sink down into your paint to not only move through the world faster, but also up walls and through tiny gaps. The big difference is Chicory’s complete lack of combat. Outside of a few occasional boss battles (which themselves are completely skippable and / or non-failable thanks to your infinite, and not to mention instant, retries), Chicory’s world has no tangible threat. At least, not initially. When all the colour in the world suddenly disappears one day, Chicory (the character, not the game) decides she’s had enough. She wants to be rid of both the brush and her role as the world’s magic paintbrush Wielder. Someone else can top up the world’s colour supply for a change - and the first person that comes knocking happens to be her cleaner. Indeed, dog protagonist Pasta (or whatever your favourite foodstuff happens to be) can’t believe her luck. She’s been handed her dream job on a plate, by the person she admires most in the whole of Picnic Province. She’s over the moon, and the first half of this 12-odd hour game reflects Pasta’s newfound lease of life. With the brush mapped to your mouse, it’s such a joy swishing and sploshing it across the screen. Game pad controls are also supported, but Pasta and her brush definitely feel most at home on mouse and keyboard. Chicory (the game, not the character) takes real delight in the act of painting. While you can hand-paint everything in sight, smaller elements on the screen will automatically get filled in with a tap of your left mouse button, allowing you to quickly breathe new life into these places and get them looking smart again. Eventually, you’ll unlock new brush styles and textures, too, giving you even more creative avenues to really make Picnic your own. The colours at your disposal vary depending on your location, too, giving each region its own distinct look and feel, from the muted greys and light blues of the Sips River, to the bold oranges and blues of beach town Brekkie. (I also love that all the places and characters are named after food. It’s like one, big glorious M&S advert, I’m not kidding). Painting doesn’t just power the game visually. It also drives how you move and interact with it, acting as both a handy exploration marker for where you’ve already been, as well as how you solve its various puzzles. Certain plants grow and shrink depending on whether they’re coloured in, for example, providing makeshift platforms or springy launchpads to hurl yourself across large gaps; creepy, gaping mouth creatures in caves gobble up your luminescent paint if you colour in too close to them, preventing you from seeing where to go next; and explosive balloons can be popped to clear away progress-halting boulders. Eventually, you’ll also use your Splatoon skills to slink through small gaps and crevasses, climb up walls and waterfalls and whoosh out of gushing geysers. Lobanov and his team get good mileage out their ideas, layering them up in increasingly complex combinations that feel both satisfying to solve and a steady test of the player’s platforming skills. There is, however, a fair amount of repetition in its individual puzzle components. The fussy balloons you roll into place and burst at the start of the game are the same irritating balloons you’ll be rolling and bursting at the end of it, and there are only so many variations of springy plants you can take before everything starts to feel a teensy bit stale. Indeed, if it wasn’t for the kind of story it was trying to tell, Chicory would probably feel dangerously close to being little more than a pale imitation of its top-down forebears. But there’s a lot of heart to be found in the plights of its main cast, and for me that’s what ultimately brings it back from the brink. I’m sure there are many who will roll their eyes at its central message, about how you are always enough, even if you feel like a square peg trying to fit in a round hole, and that’s okay. But I swear, if I’d played a game like this when I was a teenager, doing that impossible juggle of trying to be as good and clever as my siblings, making my parents proud and just generally trying to figure out what the heck I actually wanted to do with my life, I think Chicory would have been a revelation. Heck, it still packs an emotional wallop even now when I’m in my early thirties, and hot damn, it’s enlightening. Best of all, it all harks back to the core of what Chicory is about: being creative. As I mentioned earlier, Pasta is shown time and again to only be a fraction of the artist Chicory is - whether it’s the slightly messy, pixellated way you paint in the world or the occasional in-game canvases you get to fill. Even the way you fight in its periodic boss battles, it’s like you’re slopping them round the head with a great big wet mop instead of hitting them with the clean, swordsman-like strokes you might have expected from something like Okami. Try as you might, everything you do looks and feels like a five year old’s finger drawing - especially it’s put side by side with the professional artwork of your pal Chicory, which could effectively be concept art for the game as whole. There is no physical way of making your art that good. And yet! Your friends and fellow Picnic-ers revel in your paltry colour splotches. They love them. They’re inspired by them. They travel around the map to see how you’ve filled it in and what you’ve done with the place. At one point you even get fan art of your own fan art, and it’s this unrelenting tidal wave of positivity that’s just so gosh-darned heartening. Chicory doesn’t stop there, either. Everything in the game is there to be added to and improved upon. It starts small with the kind of clothes you wear, which form the bulk of the rewards and treasure you’ll find scattered around the map. Want to save the world in a dinosaur hood and a pair of robo trousers? Go right ahead. You can even drag and drop the dialogue text boxes to different parts of the screen if you want to do some painting while you chat. Eventually, you also get the ability to put down collectible bits of furniture, from plants and shrubs to tables, instruments and beach towels. Sometimes you’ll do this as part of a sidequest, but you can theoretically do it on any screen you please provided you’ve got enough pieces that aren’t being used elsewhere. You can take pictures of the world using the in-game camera - which, again, is put to excellent use during a couple of sidequests (one of which is a frankly stupendous homage to Capcom’s Ace Attorney games - it even has its own Cornered musical riff!) - and create your own in-game GIFs. There are so many ways to have fun and be creative with Chicory that there’s simply no ‘wrong’ way to play it - and its no-death boss battles are a further testament to that. It’s not that failure doesn’t ever enter the equation. Chicory’s failings and those of many brush wielders before her are all dealt with in turn as Pasta delves deeper into what’s causing dark, impenetrable roots to keep cropping up in Picnic Province, and you’ll find many of its NPCs are dealing with their own internal struggles as well if you take the time to talk to them. Hearing one character open up about how small things can send their minds spiralling out of control, or how another really wants to help but doesn’t want to get in anyone’s way feels both refreshing and progressive compared to the usual chipper parade of townsfolk that populate these kinds of games, and I’m sure many will ‘feel seen’, as the kids say. I’m also sure lots of this will probably go straight over the heads of very young players - the kind who might be instinctively drawn to its charming cartoonishness, say, or those who just love colouring - but it feels important to have this kind of emotional representation all the same. Ultimately, Chicory: A Colorful Tale lets players pour as much love and soul into making it their own as the developers have, and I can’t think of many other games that allow for that kind of relationship with their audience outside of dedicated life sims. That in itself feels monumental, even if the depth and mechanical variety of its puzzles is somewhat lacking. It’s a lovely, heartfelt game, and one whose story really resonated with me. It’s hard to say whether you’ll feel the same way, and there will no doubt be some who think it’s worthy with a capital W. But for me, it’s up there with your Rokis, your Spiritfarers and your Necrobaristas. It’s an ode to self-expression, and that’s something worth singing about.