Every time I sit down to write, the first thing I do isn’t open up a blank document, it’s find some nice video game music to listen to. And loads of it can be found free on YouTube. Ambient music from Skyrim, relaxing compilations from Animal Crossing, lo-fi Legend of Zelda remixes Sometimes, work or study just can’t get done without my 10-hour loop of Chrono Trigger’s Corridors Of Time. Looking at the millions of comments, uploads, and views these uploads get, it’s clear that I’m not alone. If you’re reading this on a PC right now, there’s a statistically decent chance that YouTube is currently open and playing some video game tunes in another tab. And it’s only possible because YouTube doesn’t treat video game music as it does other popular music.

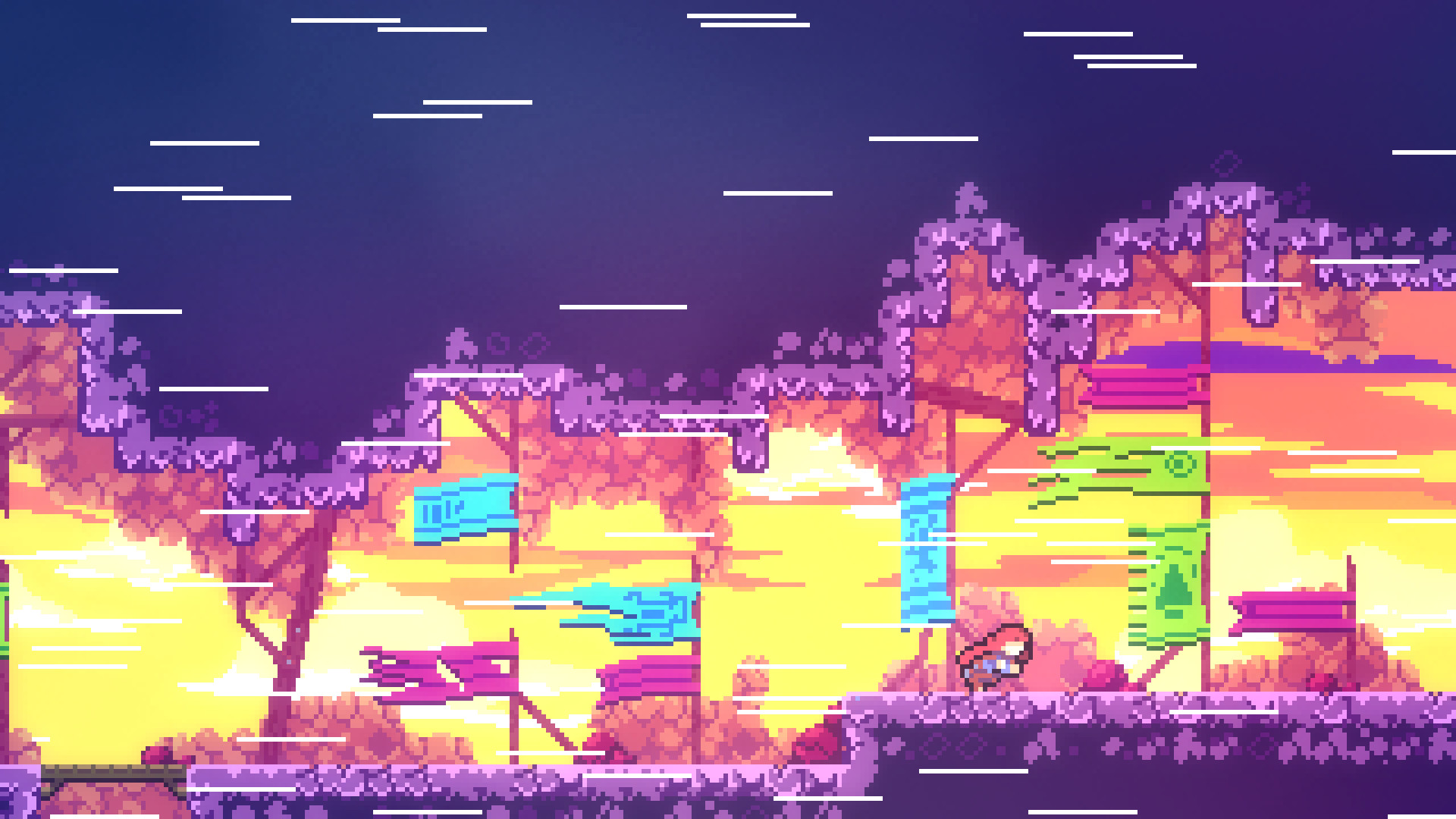

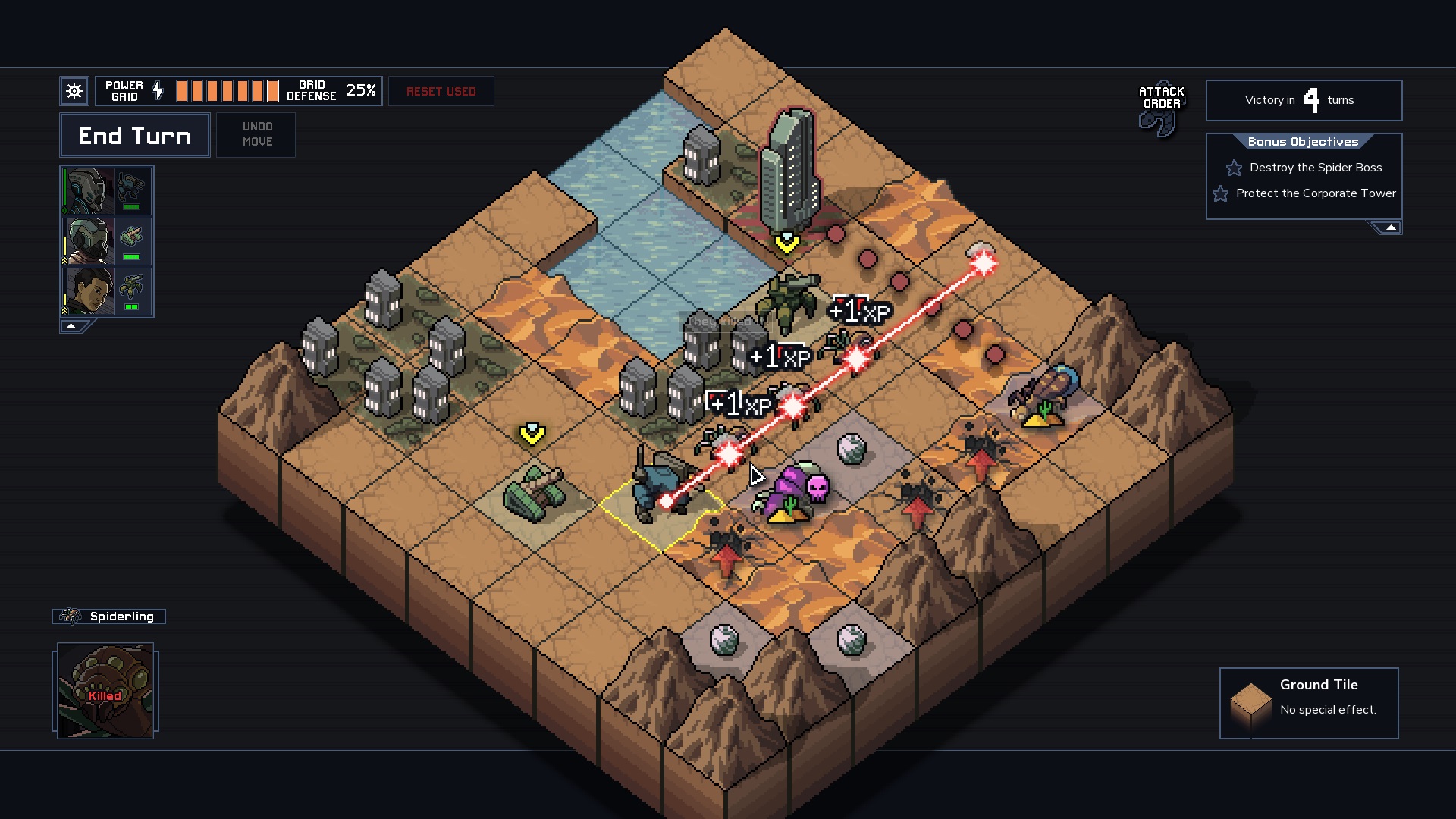

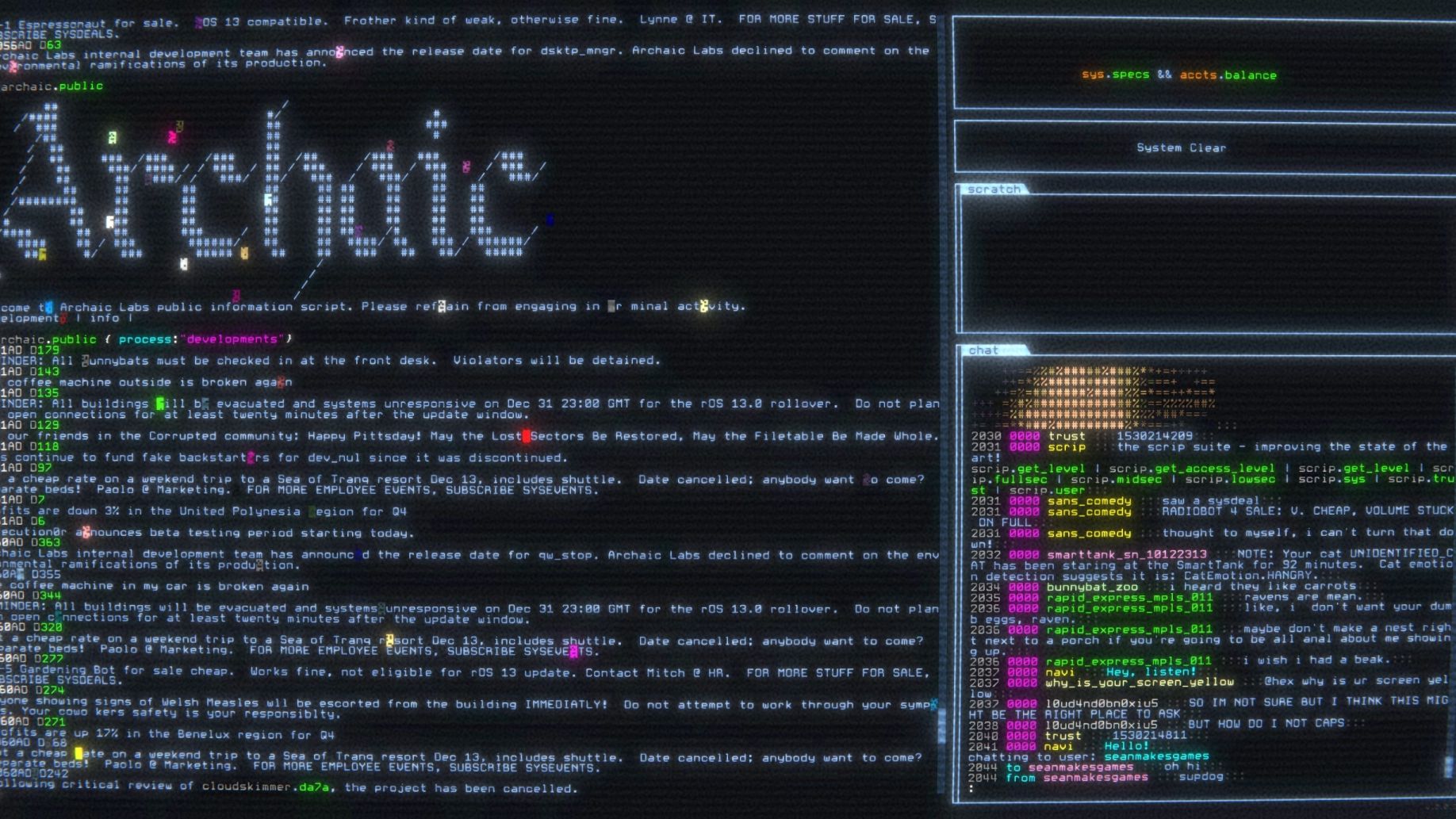

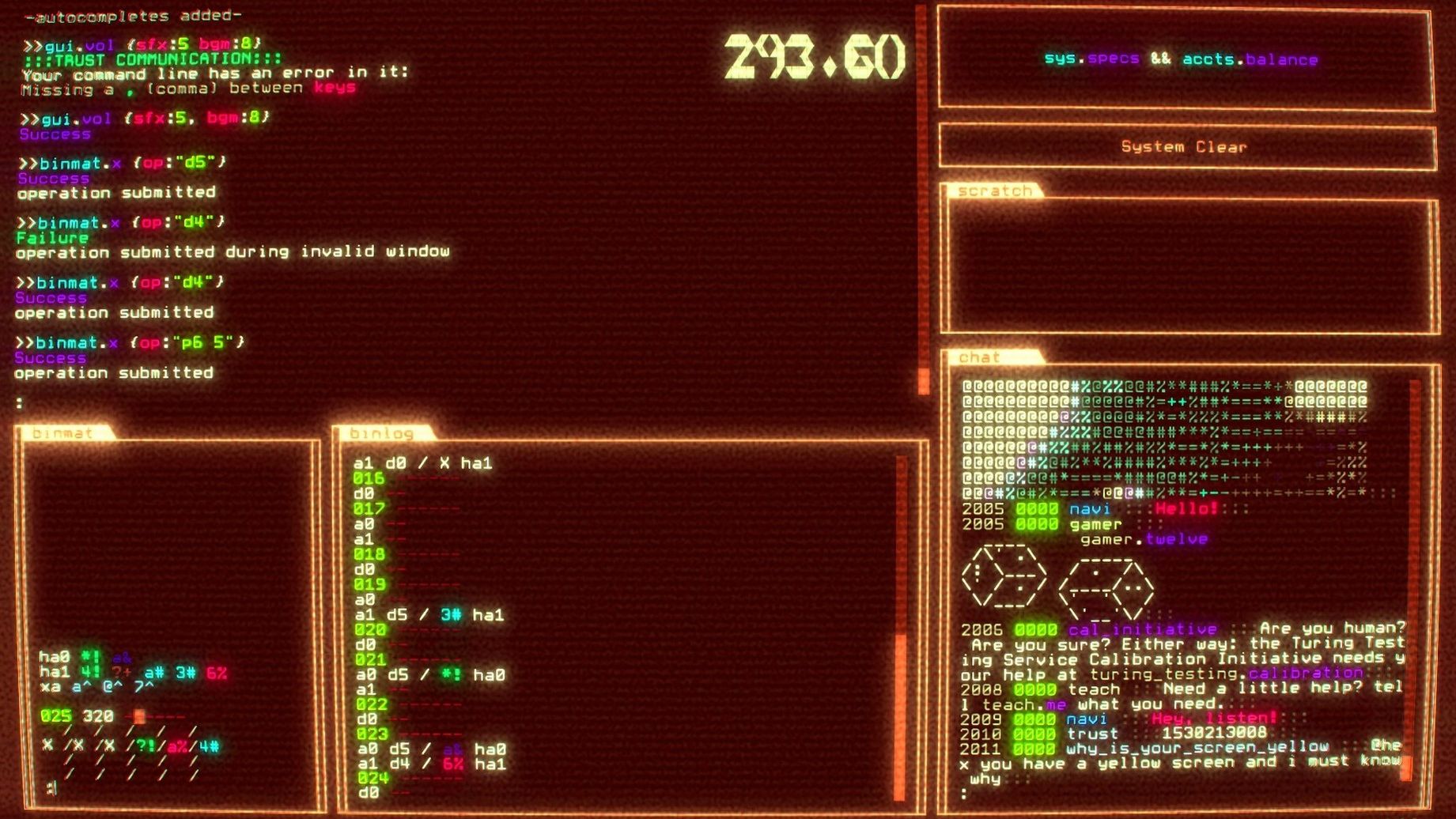

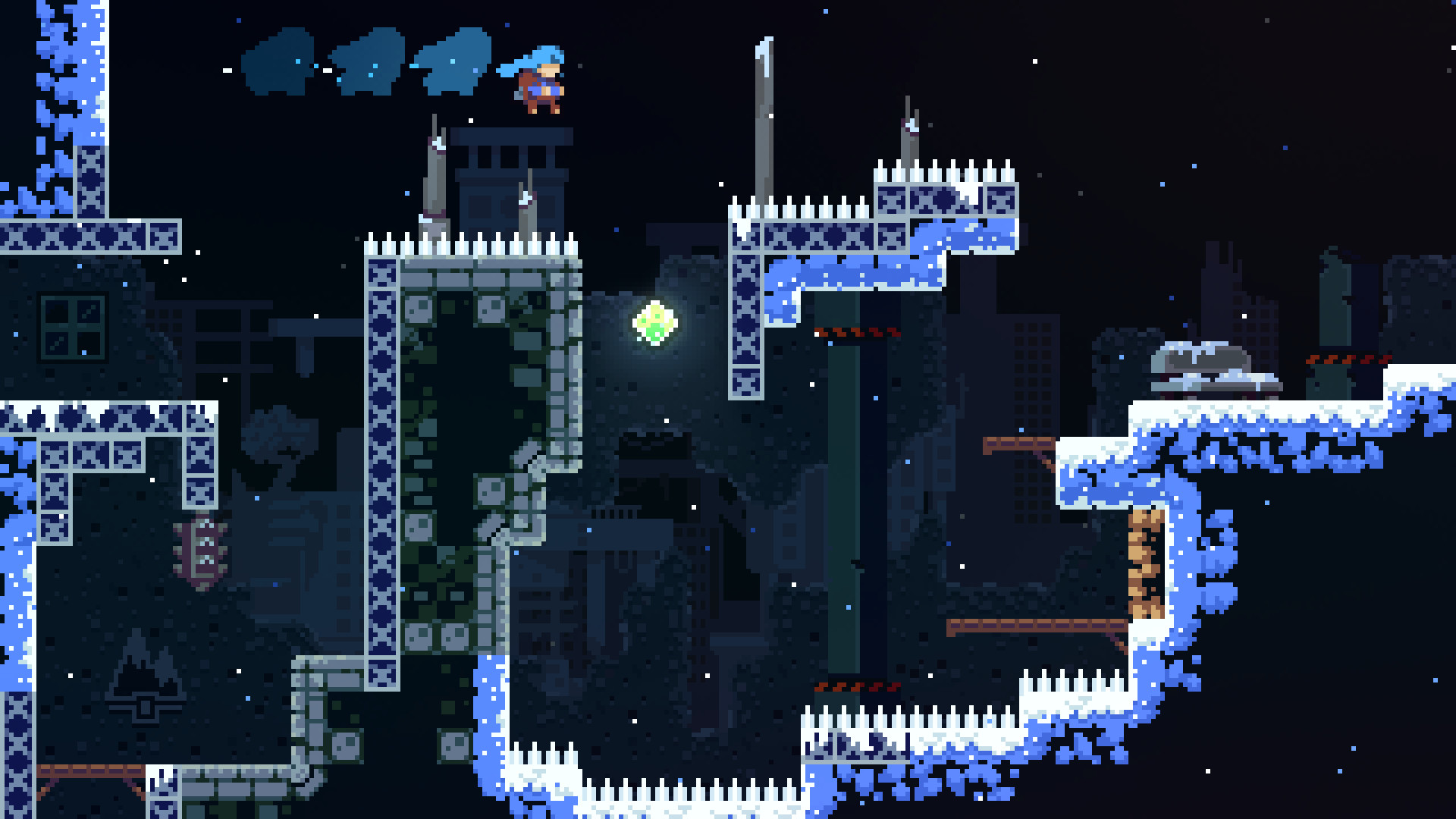

Pop music is entered into YouTube’s Content ID system and other videos that use it unofficially are automatically flagged. Video game music, on the other hand, occupies a grey area on the platform. If you’re a YouTuber, even a quick clip of pop music can be a straight trip to demonetisation, but use a random, unrelated, and unaccredited bit of a game’s score and you’re probably in the clear. For fans of video game scores, the current system is great. For the composers of video game music, especially indie composers, the feeling is very different. After speaking with some well-known game composers, I learned how often they stumble onto their own music being used in videos without relation, permission, or proper credit. That’s not even accounting for the hundreds of unofficial uploads of their own music, even if they’ve uploaded their own official versions. Hackmud “When I did the soundtrack to Hackmud, we didn’t release the soundtrack until a couple of weeks after the game came out,” said composer Lena Raine. “So someone went and took all of the raw soundtrack files and posted it themselves online.” On the next game she worked on, the indie platformer Celeste, Raine didn’t take any chances. On the same day the game was released, she uploaded both the original soundtrack and the B-Sides soundtrack to her YouTube channel. But Celeste became a huge hit, and Raine had only uploaded single tracks. Before long, videos started to use songs from the game as background for their own videos, and some channels uploaded extended loops of songs or the entire game’s soundtrack, without Raine knowing about them. It’s an unsurprisingly common story among composers. Ben Prunty, the composer behind the beloved indie games FTL: Faster Than Light and turn-based Into The Breach, told me over email that he knows there are thousands of videos on YouTube that use his music. Since the majority are let’s play videos or editorials about the games, he has no problem with them - but others with no relation to the games are a different story. “When someone puts up a video that has nothing to do with one of my games, yet it includes my music without me even knowing about it, that’s literally just stealing,” said Prunty. “Sometimes it’s attributed and sometimes it isn’t. I run my business entirely by myself, so I don’t have the time or energy to look for and flag every video.” The biggest video Prunty recalled that used his music without asking permission was a 2016 video essay from Game Maker’s Toolkit. The video was about game designer Jonathan Blow, but more than half of the runtime features music Prunty composed and self-published for the 2015 game Gravity Ghost, a game not mentioned or seen in the video. Though the tracks are properly labelled and attributed to Prunty, there’s no link to an official source and the composer himself wasn’t in the know. “Whether or not it’s legally okay for him to use my music like that is a thing I don’t have the time or energy to look into,” said Prunty. I reached out to Game Maker’s Toolkit creator Mark Brown for comment, and he replied that he’s looking to use music more responsibly. “I guess ‘I do it because everyone else does it’ is an excuse that doesn’t hold much water,” said Brown. “It’s something I’m aiming to change going forward.” So what’s the big deal, and why would composers be offended to see their music being used or uploaded? Most of the time, tracks being used on YouTube are used out of love, and indeed many appreciated the flattery. But on the rare occasion that Prunty does get requests to use his music, he always declines for one simple reason: his contracts don’t allow it. Gravity Ghost The world of video game music ownership has many common (mis)understandings. In the case of big budget development, many publishers retain the rights to the music, and each publisher also has their own policy when it comes to content being used on platforms like YouTube. Many, like Bethesda, Blizzard, and Ubisoft, actively encourage sharing art and music, while others (most notoriously Nintendo) hold onto their rights more stringently. In almost all cases, however, the only monetisation allowed by those policies is through official partnerships with YouTube or Twitch. Raising money through outside sponsorships, merchandising, or Patreon is often considered a violation, though infringements are common and rarely taken down. Indie composers, however, are often self-published. As part of negotiations with cash-strapped developers, the production deals they strike let composers hang onto their music rights and make up for lower upfront fees by making money from selling soundtracks on platforms like Bandcamp. In addition, almost all of the contracts are exclusive. If the game’s music is used on other projects, including YouTube videos, it can be a breach of contract. When I asked Chris Christodoulou, composer for Risk Of Rain, about the issue of copyright enforcement on YouTube, he said it feels like the bane of his existence. Because of how long YouTube has been around, and how much game music usage has already been normalised, many users just expect it to be okay and don’t bother asking, and those that do ask don’t always take kindly to being told no. Celeste “For every person that has asked me for permission, it means that there’s about a hundred people that haven’t,” said Christodoulou over a video call. “They’ve grown into this culture where you assume that you can do it. They assume that they can use my songs unless I am a particularly mean person.” As Christodoulou pointed out to me, YouTubers aren’t the only ones that make this mistake. Mainstream games media is equally culpable, either rarely talking about music or linking unofficial sources when they do. One example is a list of the best soundtracks in games by PCMag, complete with embedded videos and links to unofficial soundtrack uploads on YouTube. After being called out on the issue on Twitter, the outlet replaced the embedded videos with official trailers instead. Each composer had their own stories of dealing with unofficial soundtrack uploads, but Christodoulou ran into more trouble than most. When he released the Risk Of Rain soundtrack in 2013, he had decided to upload it for free on YouTube. He was beaten to the punch, however, by one channel in particular that ripped the soundtrack files from the game itself and uploaded the entire collection onto YouTube, alphabetically instead of sequentially. “They weren’t just taking music and stealing it, and it wasn’t about money, it was about exposure,” said Christoudoulou. “I was just starting out, and my YouTube channel was a forum for me to get to interact with people. I wasn’t making money from the channel, but I was building a long-term community.” “But if someone searches for the Risk of Rain soundtrack and the first link leads to someone else’s YouTube channel, that’s it. They’re not going to click the second [official] link.”

Christodoulou contacts offending channels with a comment or message, letting them know that the music was already uploaded for free. Most happily comply and remove their uploads. Some, however, are less kind. Recently, the composer reached out to a channel that uploaded music from Risk Of Rain 2, which is currently in early access, unfinished music included. After being told that the video was removed, Christodoulou saw that it had in fact simply been unlisted instead, so he got it taken down. “And then, of course, their channel got taken down and they started begging me to [undo] the claim,” said Christodoulou. “At that point it’s like, what do you want me to do?” The worst situation he found himself in, however, was having to fight for his own copyrighted music. Christodoulou recalled getting notifications from angry fans that had uploaded Risk Of Rain gameplay videos on day, saying that they received copyright claims through YouTube’s Content ID system. This was news to him, as he had been getting stonewalled from getting music into YouTube’s automatic system and he never claimed gameplay videos. While trying to figure out what was going on, his own official song uploads were claimed. Risk Of Rain 2 “The music that was listed on the claim wasn’t my track title, but it was my song,” said Christodoulou. “Someone had taken a sample of my music, put a small loop on it, and uploaded it through a publishing company that distributed it to YouTube’s Content ID system.” A lot of emails, legal threats, and plenty of worry later, Christodoulou heard back from the publishing company and the re-published music was taken down. Unfortunately, it wasn’t an isolated incident. Prunty also had his official FTL music struck down because someone had re-published it with an added drum loop layered on top. That’s why today, there’s a large and concentrated effort for composers and developers to retain control of their music. Musicians are discussing their problems and solutions together, creating guilds, and signing with publishers. Materia Collective, a record label and music publisher specifically for video game music, has been working with many musicians to ensure that they’re getting published on all platforms, retaining their rights, and are educated about the different ways their music can be used. FTL: Faster Than Light On the side of fans, the more accessible the music, the merrier. When companies take down game music channels on YouTube that upload songs or soundtracks from games, it’s understandable, but extremely frustrating. Each time, the action is met with cries begging the companies to simply upload the music to the platform themselves, and before long duplicate videos resurface. At the very least, music platforms like Spotify, and more recently Steam, have seen a growing wave of video game soundtracks added and made accessible. At first it was a few notable companies and indie developers, but over time, a growing number of publishers have made both old and new soundtracks accessible. Last year, when Square Enix released the entire Final Fantasy soundtrack collection and subsequently the Chrono Trigger and Chrono Cross soundtracks, it felt like a game music miracle. But those that do upload officially on YouTube and participate in the process need to be recognised for doing so. Everyone I spoke with expressed their belief in free, shared music, and their love of appreciation and fandom on YouTube. What they’re pushing for is to be involved and respected for the fruits of their labour, not to be excluded from the community they’ve helped build. “It’s a very tangible thing for someone to leave a comment on YouTube, say they love our music, and see me reply saying thank you and that it means a lot,” said Christodoulou. “Suddenly, that’s the world to them.” Into The Breach For at least the foreseeable future, however, composers will continue to have an uphill battle when it comes to YouTube. Barring a monumental shift in the company’s policy, the difficulties of having music used or uploaded without permission will continue. Adding game music to the automatic Content ID system will create a nightmare of taken down let’s play videos, reviews, and even other official uploads that no one, not even the composers, want. At the end of the day, YouTube is bigger than the composers are. But where the company can’t change, the people can. Composers are learning to take care of and manage their music much more seriously, and they hope fans will support them. After all, proper recognition is what anyone who made creative content would want. If you’re listening to some video game music, consider whether it’s an official link or channel, or if you can access one. If you’re uploading music or using it in your own content, ask permission first. We’ve built communities that celebrate composers’ work, they should rightly be a part of them.