“There was this kind of immense presence passing over me - the overwhelming terror that the sea was reaching out to devour me, each dark wave lurching closer and closer; or maybe it was the sensation of the sky looming over me, the clouds shifting and rapidly descending to crush me beneath their weight - and I felt completely immobilised.” On getting home that day, Yan picked up a Bible. Later, he thought of joining the priesthood. Years later still, after abandoning that dream, he would translate his ideas about the divine into a videogame. Yan wasn’t raised Christian. His family, who came to the US from China, brought with them a culture of antipathy towards religion at large. His father exerted ferocious control over what he read, ate, bought and watched, going so far as to install spyware on his bedroom computer – a nurturing that acclimatised him to the concept of an all-seeing deity long before he sank his teeth into scripture. Perhaps inevitably, Yan was a wild and disaffected teen, getting into fights, sleeping around and taking drugs in a spirit of “moronic adolescent bravado and shamelessness”. A voracious reader of philosophy of all stripes (our Discord conversations touch on Kierkegaard, Walter Benjamin and Timothy Morton, to name a few), he was familiar with the Bible but regarded Abrahamic religions in general with “cynicism and bitterness”.

Studying the Bible in earnest for the first time, Yan discovered a world of enticing inconsistency. Christianity, he explains, is awash with contradictions, but far from being deterred by this, Yan was entranced. He found in it a “fickleness and inconstancy” appropriate to his own “[vacillation] between extremities of expression and belief”. Towards the end of high school, he thought seriously of turning his emerging faith into a vocation. He hit the books with a vengeance, learning Latin, classical Greek and Hebrew. He attended open house days at seminaries, and snuck into graduate classes in religious studies at New York University. But there was a problem: “I wasn’t actually sure if I believed in God, or just the idea of God.” Yan’s faith was that of the scholar, rejoicing in “the errancy and interpretive mutability of the Word”. When he met believers who took the Word at face value, as a literal guide to living, he was repelled. On attending Sunday mass for the first time, Yan felt “vaguely sick and angered by the sheer, platitudinal mediocrity of it all.” He explained his crisis to friends as stemming from disillusionment with the Church itself. But the underlying issue was that he couldn’t empathise with other believers, and felt ill-equipped to be their shepherd. Yan stopped visiting seminaries, and fell into a powerful isolation. “I couldn’t find any order to fit in with - a common refrain in my life, echoed in nearly every aspect of my identity - and as a result I became alienated from all of it.” He couldn’t call himself a Christian, but was equally uncomfortable with the “cop-out” label agnostic. His exploration of faith and divinity needed to continue in a different form.

Yan dabbled with making mods for Hotline Miami 2. One of these, Midnight Animal, was a major hit with fans to begin with – Yan once thought of using it as the foundation for a career in AAA game development. But the mod was eventually shelved amid outrage over the narrative direction and Yan’s usage of art from the Persona series (for a fuller account, read Nic Reuben’s interview with Yan for Eurogamer last year). From that project’s ruin have emerged two others: Document Of Midnight Animal, an ambitious top-down shooter which “was basically a counterargument to everyone who claimed I had somehow lost my way”, and The Exegesis Of St John The Martyr, a bewildering endeavour which channels the fascination with textual mutability that once drew Yan to scripture. Part visual novel and part collection of footnotes, The Exegesis unfolds from multiple vantage points: an inquisitor, following up hints of an impending apocalypse; the novel’s ostensible author, who has provided a commentary that is at odds with the text; the author’s friend, trying to piece everything together; and Yan himself, at once creator and observer, “transcribing a vision that did not feel like it was mine while writing into form a kind of subreality I could not inhabit.”

If all this seems hopelessly abstract and inchoate, The Exegesis aims to find the humanity in each of its authors via the concept of martyrdom, which Yan notes is derived from the ancient Greek for “witness”. He suggests that the tension between paying witness and the inevitability of oblivion and forgetfulness is “the fundamental dynamic behind faith”, divine love ultimately being the force that transcends the limits of human memory. Once completed, The Exegesis will cap a series of experimental projects about faith and divinity. That series begins with My Work Is Not Yet Done, which itself begins, like Dante’s Inferno, in the wilderness. Its protagonist, the grim-faced Avery, is part of a team sent by a theocratic Empire to investigate a peculiar signal, deep in the overgrown, procedurally generated Reach. As the curtain rises, Avery’s companions have vanished, and she must decide how to continue the mission - a quandary that builds on two concepts from Yan’s theological studies, tristitia and acadia. “Tristitia is more like what we would describe today as depression,” Yan explains. “It’s a physical and psychic exhaustion that drained monks of their ability to work, because they were sitting in monasteries in the dark for years on end.” He describes acadia as more of “a spiritual or philosophical weariness”. “Over time, encountering so many different ideas and interpretations, you come to the question of whether there is a god. Which is kind of where Dante is at the beginning of the Inferno. He’s lost his way, both in the material and spiritual world.” Rather than following Dante down into the circles of Hell, there to rediscover faith, Work lingers in the forest of doubt, digging into that profound sense of fatigue. On a mundane level, it’s a point-and-click survival game with horror elements, pitched somewhere between the lowering menace of Acid Wizard Studio’s Darkwood and the neutron-star density of Dwarf Fortress. It includes fairly detailed recreations of illness, hunger and excretion - as Yan concedes, one less cerebral inspiration was the experience of shitting in the woods.

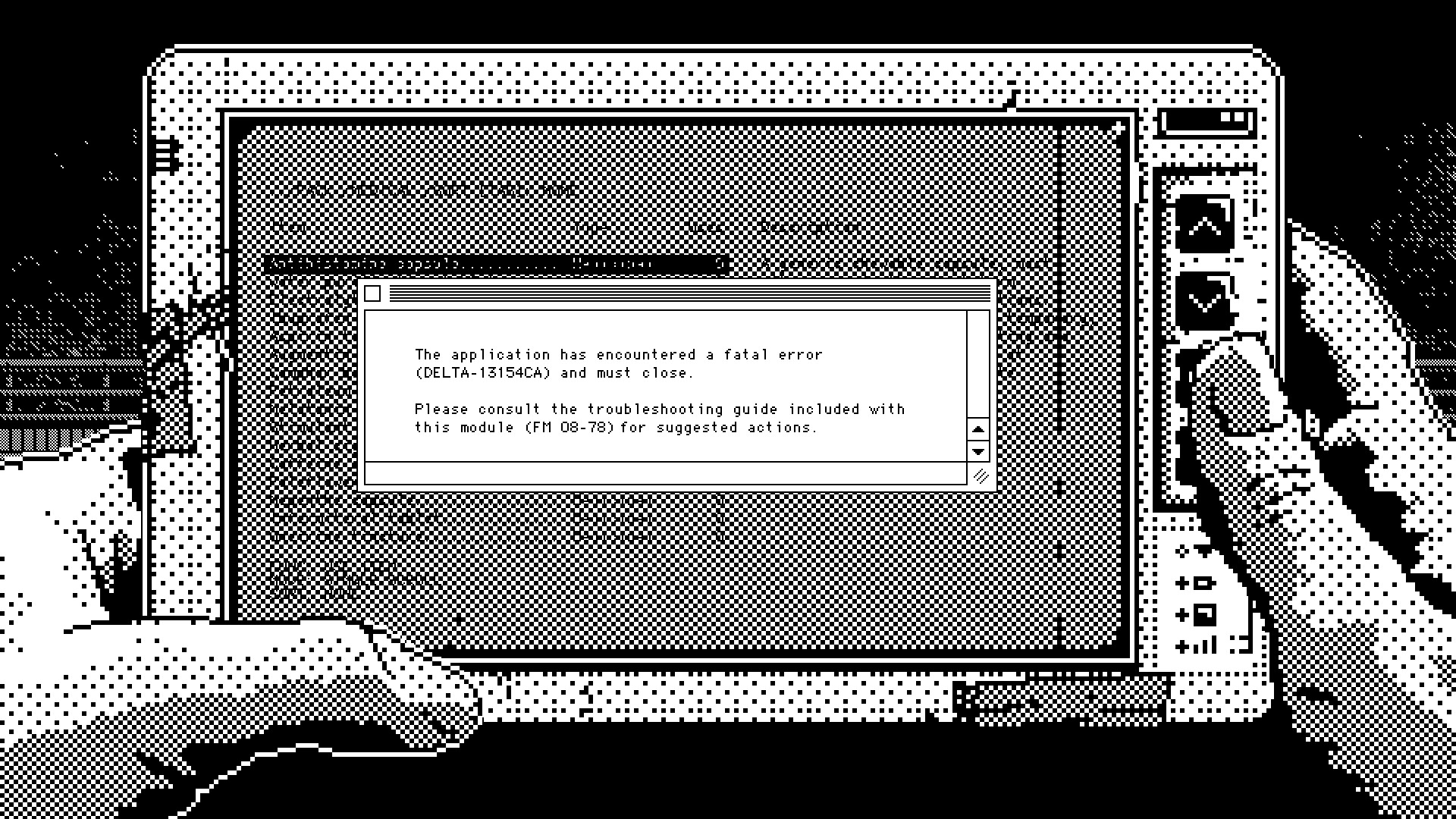

But this isn’t simulation for simulation’s sake: the mechanics are designed to illuminate “an alienation from self that comes through too much introspection.” Survival isn’t just about subsistence but fashioning an identity when you’re alone and unsure of your relationship to reality. Avery is caught between two broad visions of existence. On the one hand, there’s the disquieting, destabilising Reach, a fecund wasteland rendered in seething monochrome, as though filmed with a Gameboy’s camera. On the other there’s the Empire, not so much a country as a “state of mind”, which has recast all of history in its image. Unlike the brittle goose-stepping caricatures of so many videogames, the Empire is to some degree a benevolent force, drawing upon the ideal of the Kingdom of Heaven on Earth. Lacking a traditional military, it prefers to assimilate rather than destroying whatever lies beyond it. You’ll use the Empire’s tools to get by – Avery’s best friend is possibly her 3D printer, which allows her to synthesise food and gear. The process of crafting thus becomes an affirmation of loyalty, a re-inscription of the Empire’s rule, even as the peculiarities of the Reach put its conception of the universe under stress. “She’s out in this area that’s completely estranged from the Empire’s influence and control,” Yan explains. “She has to cope with that dissolution. And in that sense, I’d say it’s a pilgrimage, because not only is she moving towards some inscrutable destination that has these quasi-theological implications, but she’s also moving both towards and away from her own faith, and the construction of identity around her faith.” Avery is also continually moving toward or away from the player. The character is no mere extension of your will. Rather, you play coordinator, giving her instructions she may decide to refuse. The dissonance between what the player does and what the character does is an idea Yan has “always been interested in as a developer”. And Avery isn’t just able to resist you; she knows things about the world you don’t. This gap in knowledge is dramatised by the game’s save system, which sees you bashing keys blindly while Avery types out an account of her findings.

The player’s own perspective has an uneasy half-life within the game. You appear to be viewing Avery through a camera, complete with a zoom function and focusing ring. The viewpoint suggests a drone on the skyline, combing white noise for heat signatures. But if the implication is that you’re a means of surveillance, you’re also denied the survival genre’s usual access to a character’s mental and bodily wellbeing. There are no status bars, mood icons or captions. “A big part of the game is figuring out her cues based on animations, the things she says, the way she talks - noticing signs of slippage.” Yan’s interest in player-character dissonance echoes the estrangement he felt while pursuing his idea of God. It cultivates a kind of horror that, to my mind, operates in several directions. There’s your uncertainty toward Avery, this guarded soul you are both responsible for and remote from. But there’s also the fear you suspect Avery might feel for you - a formless, watchful something, looming over her wherever she goes, much like the presence a teenage Yan once gleaned from the movement of clouds. Are you God, regarding a wayward believer? Is the Empire God? Or is God the Reach - a restless vegetal immensity, always threatening to swallow you and Avery up? The point may be to never know for sure. My Work Is Not Yet Done can be read as an expression of the literary sublime, what Wordsworth called the awareness of “huge and mighty Forms that do not live like living men”. There’s the shadow here, too, of cosmic horror, albeit very firmly post-Lovecraft. The game owes its title to a Thomas Ligotti story, and the Reach has plenty in common with the liminal zones of Stalker, Solaris and Annihilation. But Yan regards such conceptions of dread as dilutions, reflective of a society that, having discarded religion, now resorts to the “inferior and materialistic language and iconography” of pop culture to express helplessness before the incomprehensible. In this regard, My Work Is Not Yet Done harkens back to an ancient and essentially holy fear. “It’s this idea that at any given moment in our lives, there could be some kind of presence, cohabiting with us,” he says. “Not even with sinister intent, but it’s just there and we have no idea. And that’s fucking terrifying to me.”