And yet, sometimes I think parser games would be better suited to adapt this genre to screen. When I think about cool comic fights, my mind goes to Shikamaru Nara. Shikamaru is one of the many characters of Naruto’s ensemble cast: a lazy, but brilliant ninja with the ability to control his own shadow. He can take control of his enemies and force them to mimic his own moves, but only if he manages to touch them with his shadow first. In one tricky fight, his adversary calculated the length that Shikamaru’s shadow could stretch to, and pummelled him with a barrage of long-range attacks while remaining just outside his range. Shikamaru bided his time, though. With every passing minute, the sun went down, and Shikamaru’s shadow grew a little taller. By the time the opponent understood what was happening, it was already too late: Shikamaru had made his shadow slither inside a tunnel, taking advantage of the dark space to extend behind his enemy’s back. He took control, and won the fight. Shounen mangas are full of characters like Shikamaru: fighters with unusual powers governed by a rigid set of limitations. For them, each new enemy is a living puzzle to solve. Who is the new challenger? How does their power work? What are the limitations, the rules to bend, the loopholes to exploit? A good fight is half about the action, and half about those rules. It’s a tricky balance that is hard to transpose to games. The first issue is one of pacing. Paper has a special power: it can control time. In the world of comics, seconds can sketch into pages and hours can be reduced to a single panel. Long internal monologues and action sequences can be woven together in an elegant flow. But this mixture of thinking and fighting can feel awkward when transposed to other media. Just think about the anime adaptations of popular shounen like Dragonball and One Piece, filled with incredibly long fights that drag for multiple episodes in a way that feels more ridiculous than exciting. Videogames usually solve this issue by scrapping the internal monologues entirely, focusing everything on the action instead. Manga mash-up fighter Jump Force isn’t interested in looking like a comic, opting for a hyper-rendered (and slightly disturbing) art style instead. But it feels like a comic, from the moment you first press the dash button and watch your character disappear, only to appear in front of the enemy an instant later. The art might be semi-realistic, but the action is stylised to the max, with quick cuts and exaggerated moves that mimic the pacing of a comic book. Not much time for thinking here.

The second issue is one of balance. Trickery comes into play when raw power isn’t an option, when you know playing fair won’t be enough. It’s always cool to see the underdog pull out a clever trick, but this kind of dynamic requires a power imbalance that can’t exist in a traditional, multiplayer-oriented fighting game. Sure, each competitive game will develop tiers lists, and some characters will be slightly more powerful or easier to use than others, but true asymmetrical gameplay is not an option. American superhero comics tend to be less cerebral when it comes to fights, but put an even greater importance on power tiers. There’s a strong hierarchy at play in the multiverses of DC and Marvel comics: some heroes are made to fight pickpockets, and others are made to fight gods. And comic fans love to debate imaginary tier lists; to wonder whether Goku would be able to defeat Superman. In games like Marvel vs. Capcom, a scrappy comic character like Rocket Raccoon can go face-to-face against the God of Thunder, and win — not because of some clever trick, but simply because some players love Thor, others prefer Rocket Raccoon, and they all want to play together as their favourite heroes and have a good time. All characters must be equally viable.

The third issue is a mechanical one. If you want to think outside the box, you have to build the box first. Redefine superhuman powers not as moves, but as a system governed by rules. You want mechanics that allows players to combine, mix and match effects with the flexibility of Magicka, or a good parser game. There are games with really interesting battle systems out there, though none are based on comics. Codespells allows you to create your own magic spells through a programming interface. Spellbreak promises to bring personalised spells to the world of battle royale games. But there’s a reason why such flexible systems are a rare sight in games: they’re hard to make, harder to master, and I suspect they would ultimately provide little satisfaction to comic book fans.

We play fighting games because we want to feel as cool as they look. Now, with such a large number of fighting games based on existing properties, there’s an extra layer of appeal. We want to replay iconic scenes from our favourite comics, and play as our favourite characters - or at least inhabit their world. Fanfiction sites are rife with self-insert stories, and licensed videogames want to appeal to those fans. Games like Naruto to Boruto: Shinobi Striker allow you to create your own very special fighter, hang with your favourite heroes, and learn all their iconic moves. Perhaps you’ll never be able to make up your own moves, or come up with your brilliant strategies, but let’s be honest: none of us is a genius ninja tactician like Shikamaru. Even with the freedom to think outside the box, we’d mostly come up with terrible ideas. The more freedom and flexibility you add to a game, the more you put the weight on the player to be the makers of their own coolness. You risk turning an empowering narrative into a Souls-esque, gruelling affair. And nobody wants to feel like that if they’re after a power fantasy.

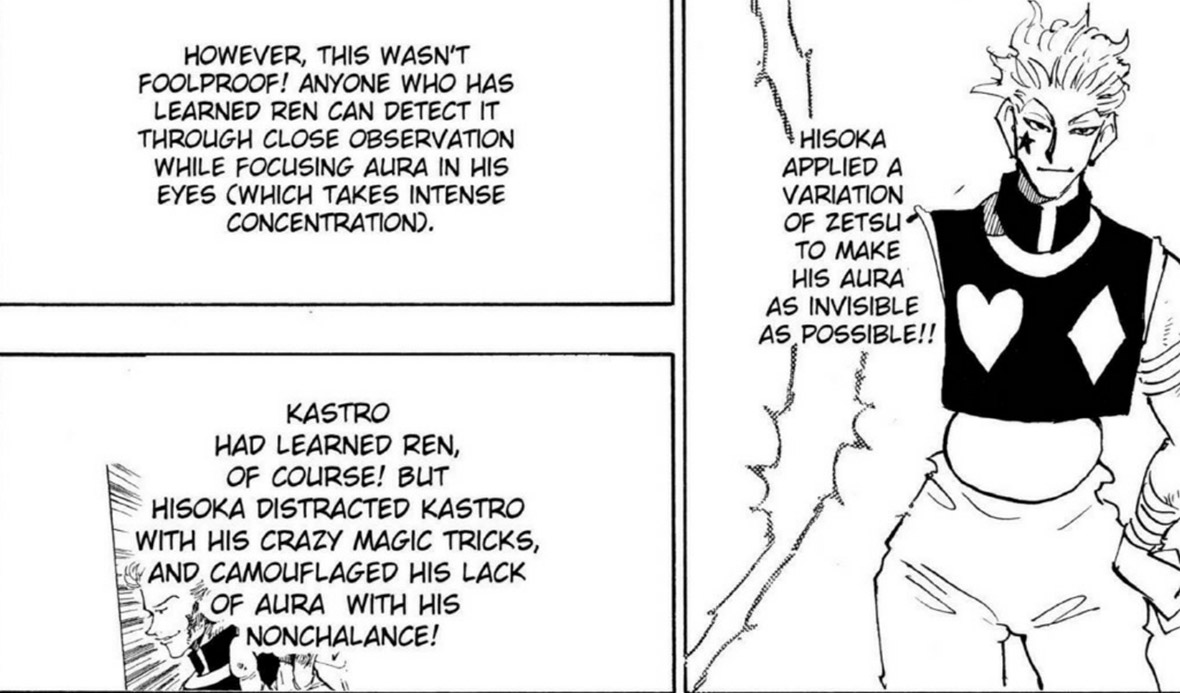

And yet, part of me still wants to see developers try (and probably fail) to capture that magic. I want a Hunter X Hunter parser game, and a Naruto game that mixes real time combat with turn-based planning phases, like Valkyria Chronicles or Transistor. I want to see more weird experiments like that Marvel-themed Diablolike. I want more games where your powers aren’t exclusively offensive. I want a JoJo game where the Stands are truly represented in their weirdness. The battle for balance between brain and brawn is a hard one. Perhaps you think it’s not even one worth fighting. But the best action comics have always have been the ones about fighting against impossible odds.