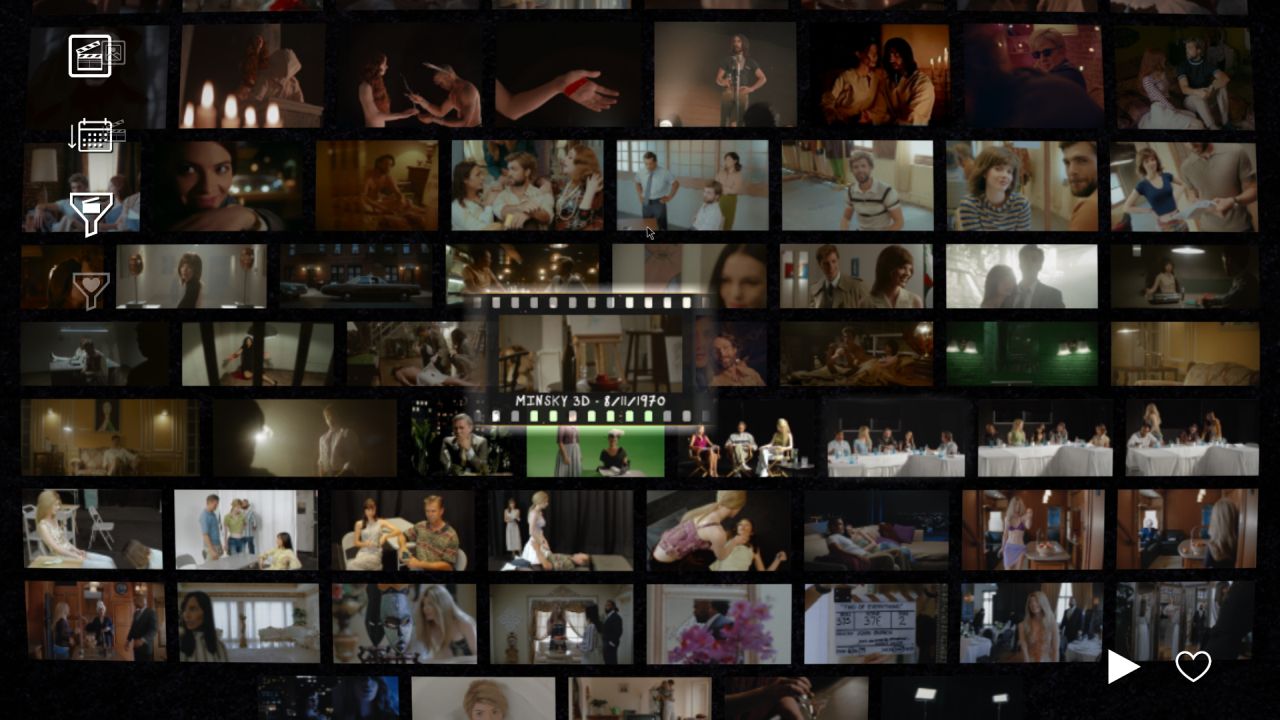

In typical Barlow fashion, the entirety of the footage isn’t easily spooled through. From one starting clip you’re able to watch it, flick back and forth through the recording, and pause it to use the in-game search tool to focus on a face or object on screen. Selecting it will then take you to that face or a similar object in a different clip, and eventually you build up a much fuller catalogue of footage. Now. Immortality also talks quite a bit about sex, in various ways and for various reasons, and there is female nudity. So yes, you can enhance! Zoom! on a tit. And the game will take you to another clip featuring a similar tit. Ba-dum, tsh! You’re already thinking, “Aha, but that’s the point. The very fact that you tried to select the tit is a commentary on the voyeurism that you yourself were engaging in by playing this game!” And to that I say, “Sure.” Look. We’ll circle back to this. Put a pin, so to speak, in the tit, while we talk about Marissa’s career. The three films in question are called Ambrosio (a 1968 adaptation of 1700s gothic novel The Monk by famous director Alan Fischer, and Marissa’s first ever film), Minksy (70’s cop thriller that was shelved when an actor died in an on set accident), and Two Of Everything (a more modern kind of psychological thriller made in 1999). As you piece them together you come to realise the films are all actually quite bad, but in different, very well-observed and period specific ways. I laughed out loud at several scenes, possibly loudest for a scene in Ambrosio where Marissa, dressed as the virgin Mary, appears in Ambrosio’s room and sticks his finger in her mouth. The other two movies were written by John Durick, the DP on Ambrosio, and it is apparent that Durick is kind of an unimaginative hack with quite an adolescent mentality, even though he obviously thinks he is very insightful and interesting. You can see, too, how he picked up habits or ways of working from Fischer. A downside of this is that, despite how well made they are in their context as bad films, you do still have to watch quite a lot of them in the course of playing the game. Still, it absolutely has to be said that the ways different filming styles and techniques are replicated, and the performances that the actors give, are all extremely impressive. In particular, Manon Gage as Marissa - and as Marissa as different characters - is fantastic, switching on a dime between innocent, bubbly, confident, charming, kind of a bully, and openly sexual. (Gage, incidentally, appears to be crowdfunding for a drama series about a camgirl who “accidentally meets the wife of her most twisted viewer”, which is enough of a coincidence that it caused a hot second of wondering if Manon Gage is real). Marissa’s casting as an unknown, barely adult woman by a skeezy and psuedo-Hitchcockian auteur, to co-writing a movie about the murder of an auteur artist who physically and emotionally abused his female muses, to starring in a film about a successful pop star who gets revenge for the assault and murder of her body double, runs the gamut of literal and figurative dangers of fame, film and hollywood. Andy Warhol turns up. I mean. But there’s a twist, because of course there is, and it’s impossible to talk about it without spoilers. You might stumble across a clip where, as you rewind it, something very unexpected happens. Then you start to notice that, behind the score (which always seems to rise to a kind of mini-crescendo just as you find a significant clip) there’s sometimes a bass hum. You put the two together and realise there’s a story hiding behind the story. This is why Immortality is best played with a controller rather than mouse and keyboard, not just because the controller vibrates and gives you an extra cue for where the walls between the stories are thinner, but also because it makes the experience of pushing through those walls more tactile. Dragging the mouse at a middling speed isn’t as nice as nudging the thumbstick until you feel the catch in reality and slip through to the other side, like stepping into a bubble without breaking it. What you find on the other side is certainly something, and though it offers literal explanations for Marissa’s life, it doesn’t do to read it too literally. I suspect how much you like it depends on how much you needed to know what happened after the cut at the end of The Sopranos or Inception. It parallels both the story in the films and of Marissa making the films: power, intent, self, religion, art and artists and ownership. Phrases like “symbiotic parasites” pop up with both alarming frequency and fecundity, so obviously pregnant with ideas that you’re almost afraid to touch them and release all the spores. It, unironically, really makes you think. I enjoyed it more than what goes on outside the bubble - and here we’re going to take the pin out of the tit, I’m afraid. From what I saw in Immortality Marissa - indeed, everyone around her, who are all having their own human agonies - is an extremely interesting character. She’s shown becoming more and more fulfilled and confident in a way that is linked to her sexuality. During a secret lighting test for a scene they think would be good for Ambrosio, Marissa strips off and simulates riding Durick to orgasm, before telling him to have sex with her for real but with the camera on a close up of her face. She declares her intent to seduce her male co-star in Minsky during a random location scouting trip, and then absolutely throws herself at this task. There are hints, in the subtext of the movies that she’s involved with, that Marissa may have been in abusive situations. Maybe I missed some pivotal clips with respect to that; it’s possible, due to how the game works, that you’ll see something different to me. The much more explicit text of the game I played is that Marissa is a woman who enjoys sex, is unembarrassed by this, and also feels powerful through it. Within the context of Immortality itself it’s pretty cool. It’s the subversion of a situation, drawn out by things like a veteran male actor objecting strongly to having to be nude in a scene as an unworkable situation, but having no issue with Marissa “cavorting around”. Marissa is, in many ways, admirable. But also, I’ve just read Catch And Kill, and I couldn’t stop thinking about how outside Immortality, we know what actually happened and happens to young actrors in that kind of situation, and how the trope of women being seductresses who wanted it is weaponised. I was aware of how Immortality fits into the world as a piece of media that could be subversive and interesting, but could also be… not that. And you’re right, the point is that I was supposed to click on the tit and then think about what I’d done. But the scene in question was set up to make you do that. The nature of the game is that, unless you’re specifically looking for a person or thing to track through the clips, you usually click on something in the final frame to keep your journey going. The clip I’m talking about was staged and framed and costumed and edited so that a naked breast is one of the most prominent things on screen right at the end of the clip. So when I clicked on it I wasn’t tricked into confronting my own latent perversions; I knew what was going to happen and I wanted to watch, chin in hand, as the game underlined some key points in its lesson plan. I didn’t think about what I’d done, I thought about what Immortality had done. It’s not as clever as it would like to be. When you’re examining voyeurism via film (which is basically the easiest, best way to do it, right?) there’s the audience, but there’s also the camera and what the camera is filming - what someone is making that camera film. You might be intending to raise a lot of points about watching people and titillation and women in art, but it doesn’t stop the scene in your game where a woman is simulating sex from starting feel, at the point where she rubs her own spit over her breasts to make herself look sweaty, a bit much. None of this necessarily negates the good, interesting things about Immortality. The negatives I took away are complicated, tangled up in lots of things and might, ultimately, mean nothing to you, or mean something different. I don’t like lampshading myself as a reviewer, but I feel moved to say this out because I’ve critiqued the sort of things in Immortality that can make people who like a piece of media very defensive. You’re still allowed to like this game. You can like it for the formidable performances and the unbelievable replications of different periods of cinema, for the sets, the artistry, the surprises, the big thinking and the weirdness hiding just the other side of the curtain, for the attention to detail and the vaulting ambition, for the way it’s thoughtful in how it stages certain things. But, for me, Immortality wasn’t as thoughtful about other things. Perhaps I’ve just had enough of Sam Barlow’s ideas about women on camera for a little bit. I’d quite like him to have ideas about something else next time.