This is a question that’s passed the lips (or rolled around in the brain) of many an aspiring PC builder, and the honest answer is “it depends”. Liquid coolers and air coolers do their thing in very different ways, using very different form factors, and at very different price points – so it pays to do some research before you install your CPU and turn your attention to keeping it chilled. Hopefully, by the end of this guide you’ll know which type is right for you, as together we’ll go over how these coolers work as well as the key advantages of each. To clarify, when I say “liquid cooling”, I’m going to be referring specifically to closed loop, all-in-one (AIO) liquid coolers that anyone can buy and install with relative ease. There is also, of course, the open loop style of liquid cooling that involves installing a reservoir inside your PC and channelling coolant around your various components. Open loop systems perform well and are modular, but are so expensive and tricky to install AIO coolers are simply better for first-time builds and upgrades.

How liquid and air coolers work

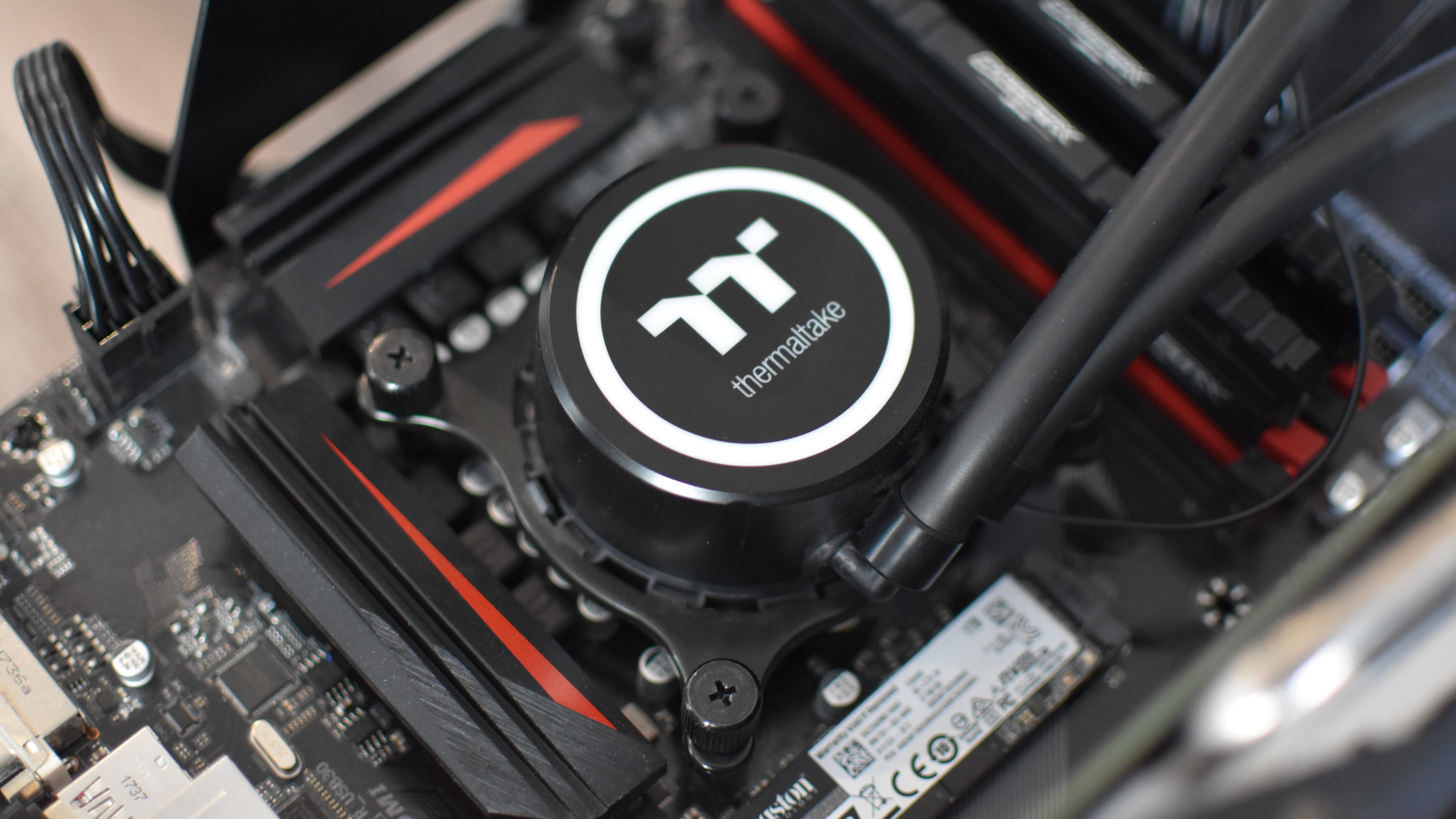

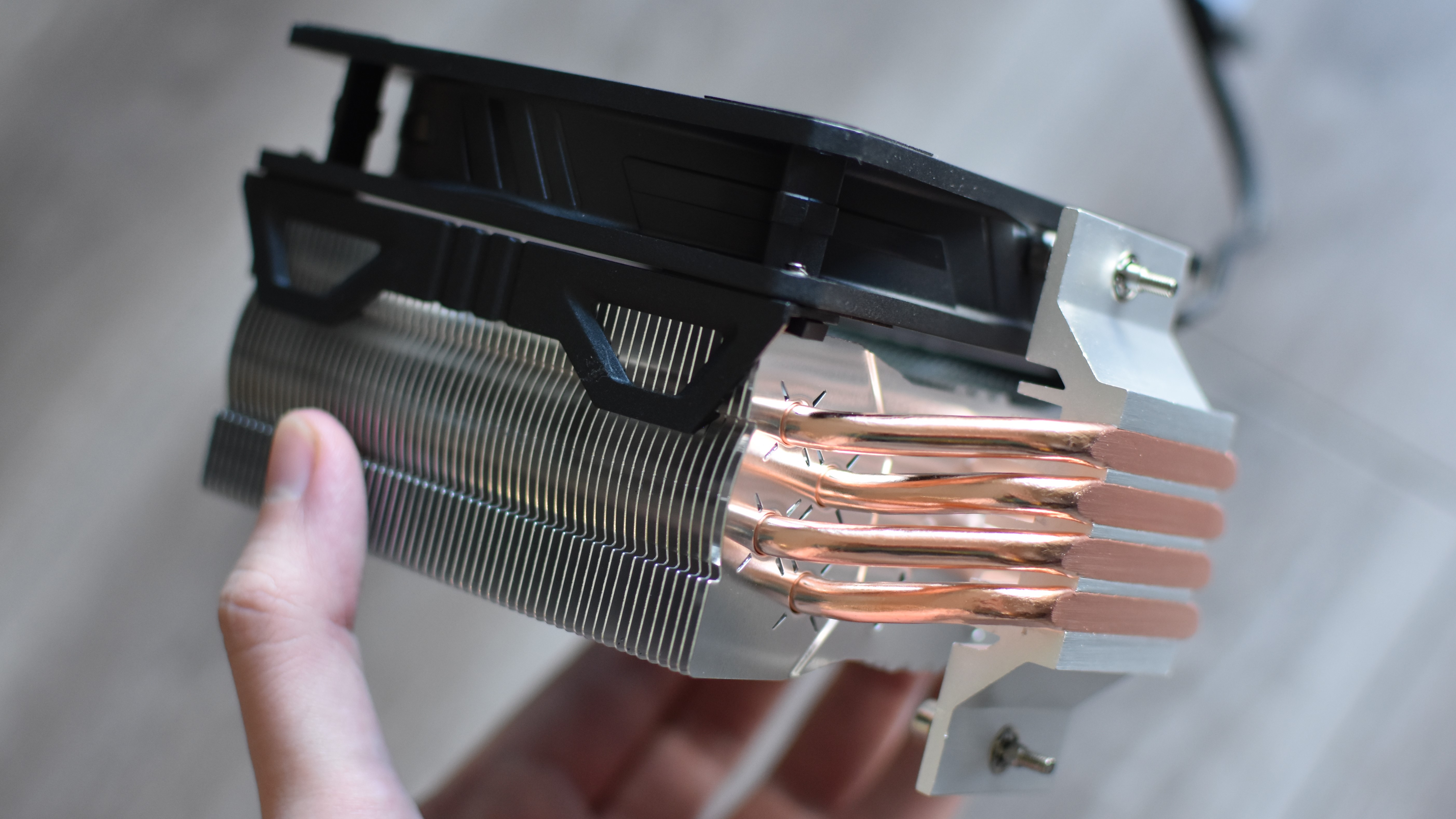

Both cooler types prevent CPU overheating by essentially transferring heat from the processor to a radiator, where a fan (or fans) can blow it away in the form of hot air. To get to that same end result, though, air coolers and liquid coolers employ very different methods. On an air cooler, heat is initially conducted onto the cooler’s contact plate (also called a cold plate), then transferred again into the heat pipes: the metal tubes you see extending from the contact plate all the way up to the top of the radiator. These pipes contain a fluid that evaporates to facilitate heat transfer to the connected radiator fins – that’s right, an air cooler still has liquid in it. Or at least it does before quickly becoming a gas. Even so, the “air” part is paramount, as the fins heat up and start warming the air around them. This hot air – which originally began as CPU heat – is then pushed away by an attached fan, where it can ideally be vented out of the case by an exhaust fan. Meanwhile, the evaporated fluid gets condensed after reaching the top of each heat pipe, then trickles back down so the process can repeat. Liquid coolers affix their contact plates to a small pump, which controls the flow of coolant to and from a radiator via a pair of long, flexible tubes. Heat is absorbed by the coolant then pumped to a water tank on the radiator, from which it disperses across one half the radiator fins, transferring the heat to them. Attached fans then blow away the heat as it comes off the fins. At the opposite end of the radiator to the tubes, the liquid turns around and flows back across the other half of the fins, eventually reaching another tank from which it returns to the pump. Between transferring heat to the fins on the initial pass, and being cooled by the fans on the return pass, the liquid becomes cold enough to once again pick up heat from the CPU and continue the cycle. Physics!

Why liquid cooling?

Although it’s possible to find high-end air coolers that can compete with liquid cooling on temperature lowering performance, the latter has a couple of advantages that make it more efficient – and therefore preferable for powerful CPUs and/or overclocking. The first is the method of transferring heat away from the contact/cold plate: liquids are better at conducting heat than the gas-filled pipes used by air coolers, so heat is more efficiently dragged away from the processor and spread across the radiator. The second is the radiator itself: the fins of a 240mm radiator, one of the most common form factors for AIO liquid coolers, will amount to greater surface area than a typical air cooler’s radiator. Because the radiator should be dissipating as much heat as possible, more surface area – for the heat to escape from – is exactly what you want. These efficiency advantages usually translate into extra headroom for overclocking, as the CPU can run hotter without overwhelming the cooler’s capabilities, and make liquid cooler generally ideal for high-core-count processors that get relatively toasty even under medium workloads. Also, because AIO radiators are better at dissipating heat, the cooler’s fans may not need to spin as quickly to shoo away the warmth. Your PC, in other words, can run both cooler and quieter.

Why air cooling?

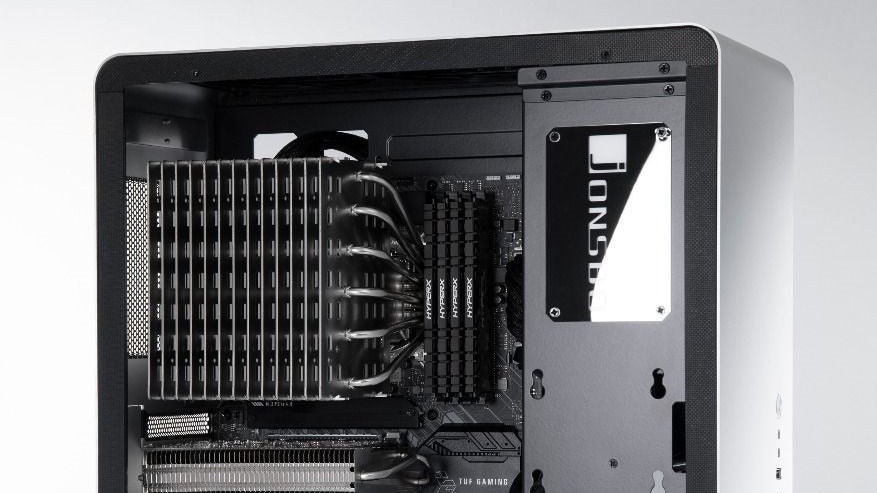

Don’t think of air cooling as the losing side, mind. In truth, most non-overclocked CPUs will be run perfectly fine on a humble air cooler, and some chips – especially those with six cores or fewer -might even be able to take a moderate OC without temps tipping into the danger zone. Air coolers can therefore make fine additions to lower-end and mid-range PC builds, lot least because they’re by and large more affordable than AIO liquid coolers. Impressively capable models start from about £40 / $40, and you can spend even less – or just use a bundled stock cooler – if your PC only houses a basic dual- or quad-core CPU. Air coolers also tend to be easier to install, making them even better for first-time builders. Not that AIO liquid coolers are particularly difficult to hammer together, but not all PC cases will have room for 240mm, 280mm or 360mm radiator and fan setups. With an air cooler, the fan usually comes pre-attached, and only the very fattest air coolers are too tall to squeeze into the majority of tower-style cases. High profile RAM sticks can make installation difficult if there’s not much space between the DIMM slots and the CPU socket, though it’s not a common issue. Some air coolers are even designed to avoid RAM clash specifically, like the Cooler Master 212 Evo V2 (£40 / $40) pictured above.

Can I try passive cooling instead?

In a gaming PC, I wouldn’t recommend it. There are a small number of completely fanless coolers, like the Noctua NH-P1 and Silverstone HE02, that rely solely on the dissipation power of their gigantic radiators to keep the chip cool. These can spread heat around effectively enough for low-end chips and some of the more efficient mid-range CPUs, but only at significantly higher temperatures than a simple active air cooler would manage. They’re more expensive, too, and tend to be chunky enough that a lot of cases just won’t have the clearance for them. Silent running sounds nice, but assuming your gaming rig has case fans and a graphics card making noise anyway, the benefit won’t be felt as keenly as if you were building a completely silent PC for work or living room use.

So which is better, liquid or air cooling?

It ultimately depends on your budget, your CPU and which exact qualities you want out of your CPU cooler. For high-performance builds, especially overclocked ones, a liquid cooler is the much safer bet, but it’s also worth taking this route if you just want to minimise noise. AIO coolers could also be consider better for future-proofing: even if they’re overkill for your current CPU, they’ll leave you in a better position to upgrade later. Again, though, a respectable air cooler can handle the vast majority of processors, especially if you’re happy to leave them running at stock clock speeds. As the generally cheaper alternative, it might well be wise for anyone building their first PC to get a more affordable air cooler and free up their budget for a faster CPU or one of the best graphics cards instead.

.jpg/BROK/resize/690%3E/format/jpg/quality/80/nzxt%20kraken%20z63%20temperature%20display%20(2).jpg)