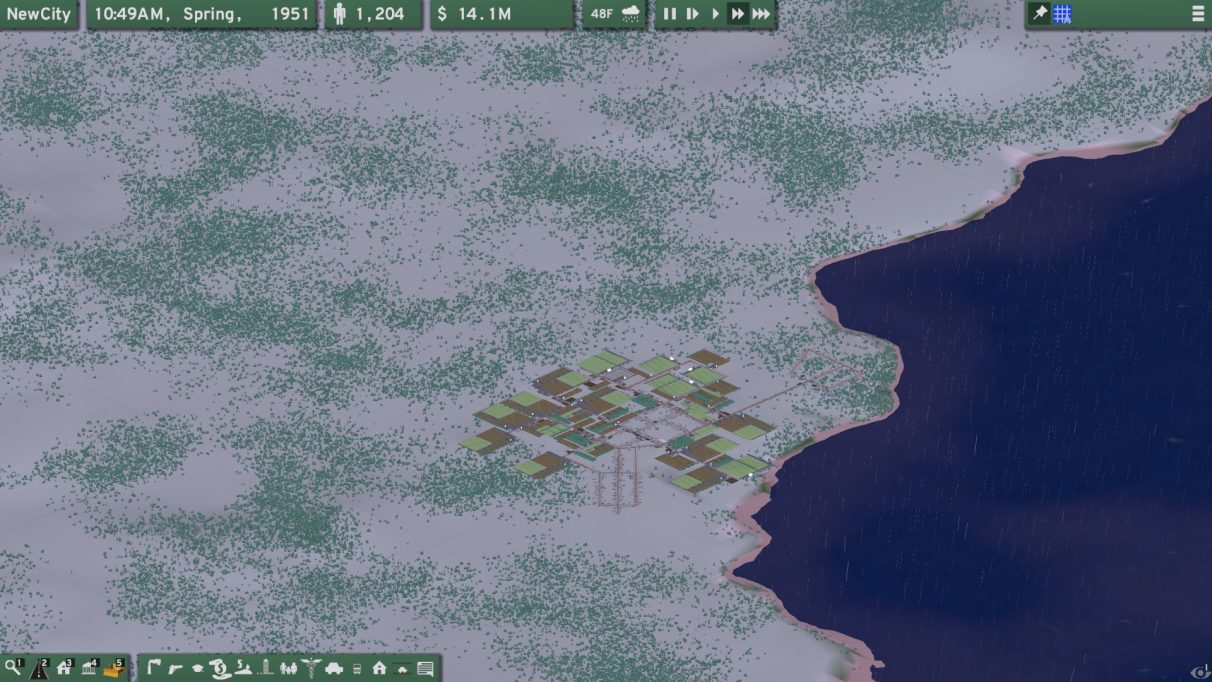

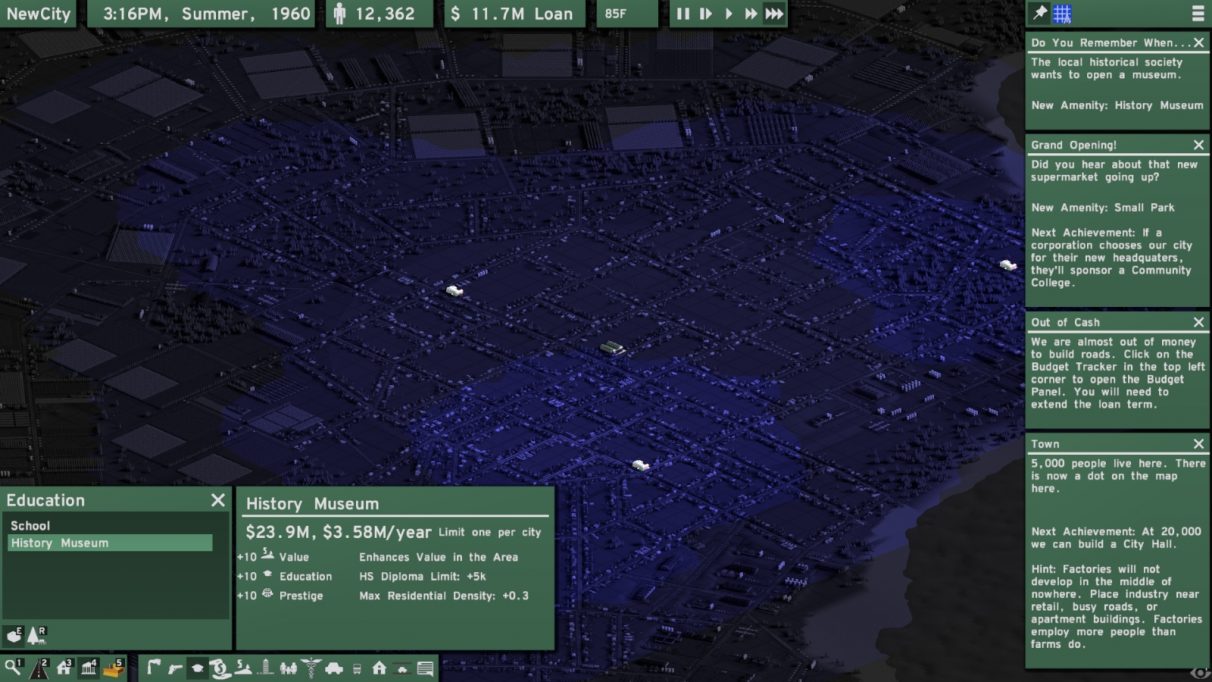

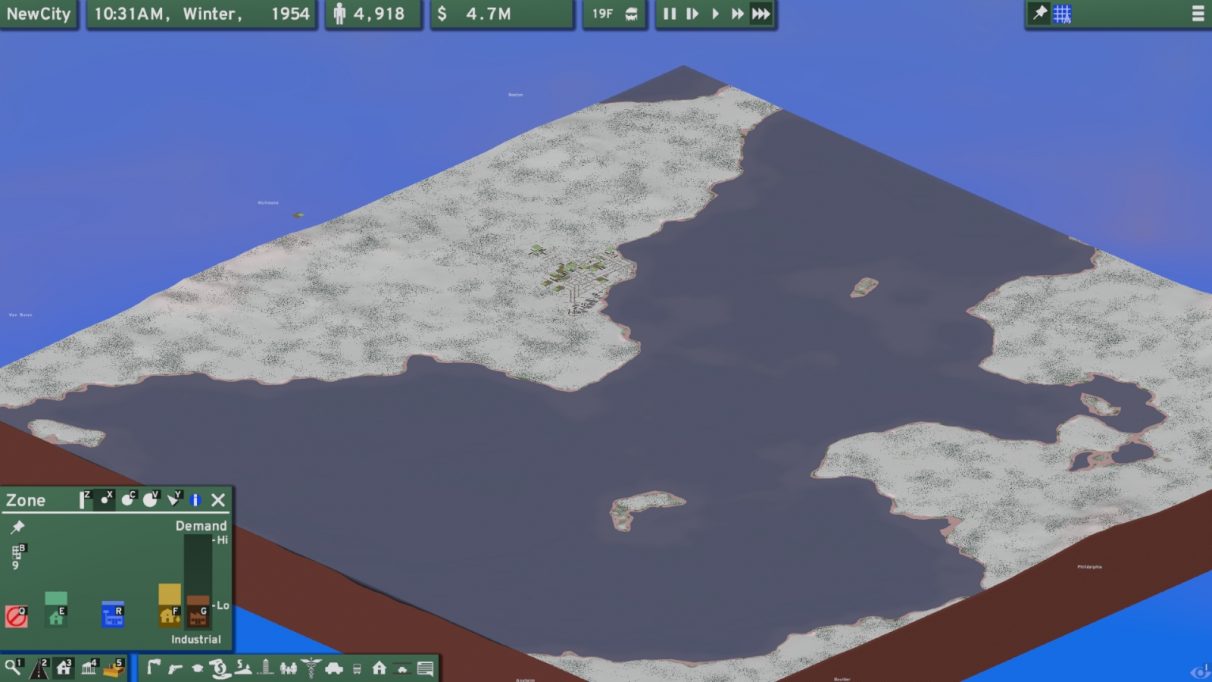

Looking out of an aeroplane window with a migraine, that is. Because for all its wonders, NewCity is, as it stands, a fairly ugly game. It stutters a bit, at least on my PC, when speeding up time in a decent-sized city, and it feels very feature-sparse, to an extent where in the early game I wondered if I was missing some menus. Its UI is bleak, and its music is - with profound apologies to the composer, who I’m sure has done much better work in other genres - horrendous. But this is early access, friends! And early early access, too, as the game’s only been up on Steam a couple of weeks. NewCity’s problems, therefore, don’t concern me, as they’re all fairly peripheral set dressing issues. The game’s core, on the other hand, feels like the foundation of something really special. I don’t feel like I need to explain the basics of NewCity because they are, ironically, nothing new. It speaks the green-blue-yellow zoning language of SimCity fluently, and can manage a decent conversation in OpenTTD besides, to the extent where anyone familiar with the general territory can play pretty much by instinct. And to be fair, this is probably one of the biggest obstacles NewCity will have to overcome, as in its early game it felt so much like a particularly barren SimCity clone, released decades too late, that I almost quit in disinterest. I’m really glad I didn’t. Because while the basic elements of the game are all borrowed from elsewhere, the way they play out in practice is impressively original. Expanding in Skylines, which is pretty much the gold standard for this sort of thing right now, is a gradual business. A bit like growing a bonsai, I suppose. You build the core of your city, then add to it slowly over time, neighbourhood by neighbourhood, stopping periodically to spend ages tinkering with road layouts. Expanding in NewCity, by contrast, is like growing a massive lawn. You make your quaint little starting town, with its carefully planned road layout, neat farm cluster and tiny commercial district, and… nothing happens. Maybe 200 people move in; big deal. So you build more. And more. And more. By the time my city had 1,000 residents, it was already the size of a good-sized city in another game, with an actually realistic-seeming sprawl of farmland surrounding it. But that was peanuts. There wasn’t even anything else to build, except basic zones, until I got to (I think) 5,000 residents. In other games, you’ll have the inevitable plopfest of fire stations, schools, clinics and the like to handle very early on, and it always feels a bit arbitrary and chore-ish. You put them down cos you have to, and it’s cheap enough that it doesn’t really feel like much of a decision. In NewCity, when I was finally allowed to build schools at pop 5000, I found they were so expensive that I could only afford the one. It meant I had to think really carefully about where best to put it, and once it was up, the education budget was high enough that I had to raise income tax just to keep from plunging into deep debt. It had been a proper, major choice, with consequences and everything. And I hadn’t just been doing it to fill an arbitrary “education” demand, either. The school did fill such a thing, but more important was its effect on the area around it - a sort of buff, if you like, which effected several different local variables. It’s different for each amenity building, too. Some allow greater housing density nearby, some affect which jobs are in demand, and some improve land value, for example. Most do several things at once, which only increases the need to think carefully about placement. After the school was up and running, I learned that my next major unlock - a city hall - would take place at 20,000 residents. And it would cost far, far more than my current city (which was straining to fund a single school, after all) could ever hope to earn. It was as if the game was at last making a statement about its identity, and it was as unambiguous as a hardman swaggering into a newly-opened pub and taking a bite out of a pint glass before staring around the room in challenge. If I wanted to get anywhere in this game, NewCity was telling me, I was going to have to build like a man possessed. So I built. More and more residential districts went up, the nascent education level from the school created some demand for light industry, and the fledgling factory quarter boosed demand for commercial zones. As all this went on, the farming orbital was moved outwards and then outwards again, with its old inner ring bulldozed to make room for even more housing. A clinic became available, and then a museum, and I really had to be smart with the city budget to make them happen. At one point, I didn’t even have the cash to finish a very moderately sized road, of all things. One thing I particularly loved was how, in compelling me to grow the city ever-outwards, NewCity stopped me taking too long to overthink what went where, at least on a macro level. I laid out new districts in sweeping strokes, filling in their road networks in chaotic tangles, so they looked like those photos from school textbooks, of webs built by spiders on loads of drugs. they didn’t look bad though. They just looked pragmatic, needs-driven, improvised… in other words, like the layout of a real city. And the way NewCity led me to that, from the basic necessities set out by the constants written into its basic population mechanic, was a really elegant bit of design. There’s more, too. I only played to a city size of 25,000 or so, and it felt like I was a long, long way from the game’s ceiling. Plus my financial management was poor enough that I never afforded a lot of the amenities that would have made my city more interesting. Another thing I didn’t get time to play with was the blueprint system, which lets you clone-stamp carefully designed bits of city in a way that could make the dynamics of expansion feel entirely different all over again. And then there’s the modding capacity, which seems to be as broad as OpenTTD’s. And this is all in week three of early access. Certainly, this is nowhere near as slick an entry into the genre as Cities: Skylines’ was. But given this is a debut effort from indie studio Lone Pine, and it’s already managed to find a fresh approach to some of the most established tropes in PC gaming, I’d say it’s bloody promising. Keep growing, little city.