2019 was a great year for PC games - aren’t they all? - but you might not yet know what the very best PC games of 2019 were. Let us help you. Every year, the RPS team picks the 24 best games of the year and stuffs them inside an Advent Calendar. One brilliant game is revealed each day, across 24 different posts. Then, when Christmas is over and all the evidence of our excess is cleared away, we gather our words into a single, convenient article. This article. As always, our selected games aren’t in any particular order, except for the final game on the list which is accurately and definitively the best of 2019. If you’d prefer, you can of course still read this article in its original calendar format. But if you want to do it the easy way, hit the page links below. Or if you’re looking for our more regularly updated list of the best PC games you can play right now, well, it’s at that link.

A Plague Tale: Innocence

Alice Bee: You know what, A Plague Tale was really bloody good, wasn’t it? Probably not a laugh a minute if you’ve got a thing about rats, though. Actually, not a laugh a minute even if you love rats. Rats do feature heavily, as a literal flood of danger and a metaphorical flood of corruption. Hugo and Amicia, children of a local noble whose family home is attacked by religious zealots, are going it alone in the medieval countryside. Their tale is mostly hardship and woe. But it’s the bits that aren’t woeful that are especially worth highlighting. The grim, goffic bits, with rats and wars and monks getting eaten alive, would be unrelentingly grim without contrast. Hugo and Amicia’s ragtag Goonies gang of orphans, and their sunny wintry days together in an abandoned castle hideout, make the bad times grimmer by contrast. Sacrificing a live a rat horde doesn’t carry the same weight if you’ve got nothing to fight for. It’s almost unrelentingly goth, though. A Plague Tale absolutely stacked it in the boss fights, but the rest of the time the one hit death nature of the puzzles and combat made it all feel tense. Some big soldier with ‘orrible breath bears down on you, while a sea of writhing, squealing rats is kept at bay by his torchlight. But I can douse your flame with my sling, matey. Not so clever now. It became almost a rhythm game on some levels: one, two, put out torch, four, five, throw explosive, seven, eight, demon rats. Hugo is what you fight for, by the way. My little chubby cheeked angel, so barely out of his toddling days. I love him so much. He’s such a little sweetheart, and he’s trying his best! He must be protected at all costs.

Alice L: A Plague Tale gave me something I didn’t realise I wanted. Or perhaps, didn’t realise I missed. A linear, single player game with a strong female lead in Amicia, and… Oh, a child. But, as Alice Bee said, Hugo is really not that bad. And I, too, was expecting to hate him. Not for any reason other than I don’t like children. In video games, or in real life. Because of this, I wasn’t even sure that I’d want to play an escort mission for an entire game. But it turns out, I did. And I loved it. There were a lot of things I really enjoyed about A Plague Tale, in fact. The medieval setting, the characters you encounter along the way, the use of light and dark to fend away those little plague ridden ratties, or having those same ratties doing your bidding… Mainly Hugo, though. I’m a little bit sad about how much bad press rats might have gotten from this, though, and I wasn’t a fan of what happened to the pig. Both pigs and rats are really very nice. But I couldn’t stop myself playing. I couldn’t bring myself to step away from it for too long, as I just wanted Hugo to be okay. And like I said before, I hate kids. (And in games.)

Noita

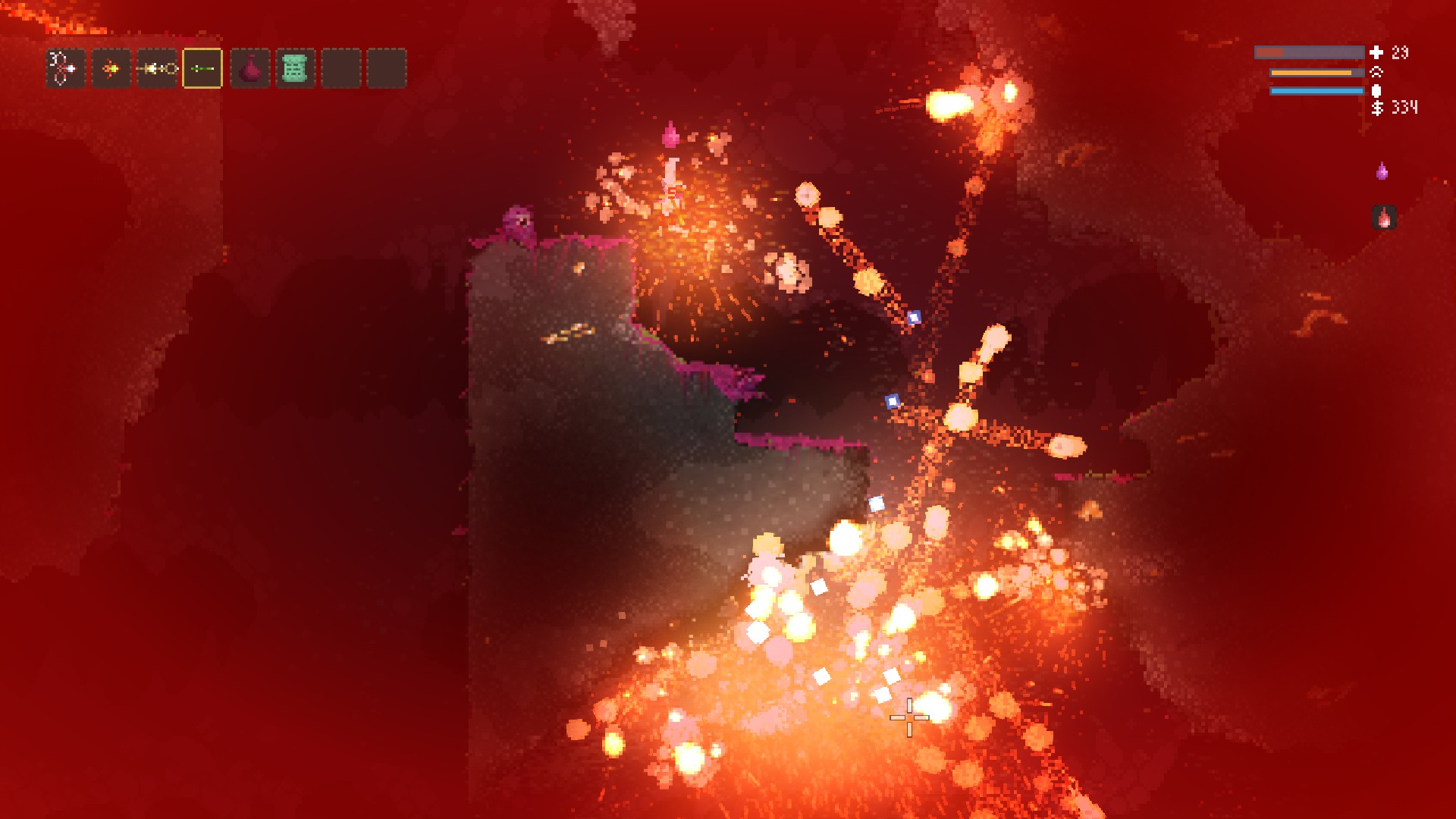

Alice Bee: Noita is an action-y roguelite. You, a small witch creature with a flappy robe, go down down, deeper and down through some nice proc gen dungeons. There are monsters. You find wands, and shoot the monsters with magic. Except! Every pixel is simulated. Every little bit in the game can act and be acted upon, to often spectacular end. Liquids pour. Ice shatters. Wood burns slowly, oil burns quickly. I am very bad at Noita, but Noita is very good. Despite Noita’s capacity for ridiculous explosions, my favourite thing to do with it is set off a slow reaction and see what happens as a result. It is a genuine joy to explore the limits of the Falling Everything engine, where lanterns drop from the ceiling, barrels explode, and sometimes you fall into a puddle of potion that turns you into a big worm with pincers. I do just, if you’ll forgive me, want to watch the world burn. This is my favourite gif that I done in Noita, where I just set a wooden vat of acid on fire and grimly watched it split and pour its contents everywhere.

We picked it as our Can’t Stop Playing game for October, and it is true! Graham has been playing it on his lunch breaks. The other day he found a wand that shot fireworks. Graham: I do play it on my lunch breaks. Also in my evenings and on weekends. I have played Noita enough now to have advanced from “crap at it” to “so-so”, but I think I love the game because getting better at it isn’t required in order to see new things. Without special effort, I am continually discovering new secrets, new locations, new wands, new liquids - love those liquids - and each time I discover a new thing, the whole game becomes about that one thing. Here’s my current obsession: worm detective. Instead of heading right and down the mine from the starting area, head left till you come to a wall. Fly up until you find a branch with a nest and an egg in it. This egg contains a free worm! Smash the egg (which is about 6 pixels by 3 pixels, by the way) and your worm may arrive in one of three sizes: a small, pointless, disappointment; mid-sized; and ‘ah geez that’s terrifying.’ Anything mid-sized and above will carve tunnels through the earth as it burrows towards you or the next nearest pool of blood. Wait for it to start tunnelling downwards into the mines, and then use the paths it has made to follow it down from a safe distance. This is great for two reasons. One, because it creates new and interesting shortcuts. Two, because the worm will cause destruction wherever it goes, and so you can play detective in its wake. The worm isn’t invincible. They tend to end up dead somewhere near the bottom of the mines, but while pursuing one case yesterday, I couldn’t find any dead worm. Instead, half the level was covered in a puddles of polymorphine, and there were half a dozen dead sheep floating on its surface. It seems that the worm had spilled a vat of the stuff and, as a consequence, been transformed into one of those fragile sheep, upon which it had been killed. Case closed. But start a new game now, because seriously, I can’t stop playing this. Sin: Yeah alright, roguelikes are bad, I hate fun, etc, etc. Noita is a winner though. It does a few too many things that irk or frustrate, and its extreme difficulty and roguelike structure fight its granular physics playground concept too much to fully win me over. But I whiled away more than a few afternoons with it, and with a few tweaks and a several decimals still left to go before its 1.0 version, it could well end up a bit special.

It’s Winter

Alice0: It’s winter, it’s night, and you are alone in your apartment within a Russian block. Snow keeps on falling, and your neighbouring block is already snowed-in. The pipes are gurgling. The fridge hums to life. The shops are closed. Most windows are dark. Your neighbour keeps clomping about but they don’t answer if you go upstairs and knock. The world hasn’t ended but it might feel like it. It’s Winter is that special kind of night aloneness. It’s isolating but liberating. The world is your playground and the rules of day are not currently enforced. Unseen, or at least unseen by anyone who cares, Hell, if you want to eat half a dozen fried eggs, that’s Day You’s problem. And you can do that in It’s Winter. You can fiddle with plenty in It’s Winter. Play with the taps. Rummage through your cupboards. Take your pills. And cook. You can use your oven and microwave to cook, frying eggs, roasting sausage, toasting bread, and such, then scoffing your midnight feast. What else do you have to do on a night like this? You could throw things around your flat. Or clear up your building’s stairs by carefully putting rubbish in the chute. Or play in the austere playground. Or flush your dinner down the toilet. Or just run into the woods.

It’s an immersive sim with no goals. It’s Warren Spector’s “one city block RPG” in a world where the rest of the block doesn’t care about you. It’s a game vague enough that I still feel like I’ve missed something huge, a big secret or goal that will turn this mundane reality into a wild fantasy. It’s nice to have a dream when you’re unable to sleep, you’re all alone, no one cares, and you’re munching on canned meat while listening to the eerie music of a half-tuned television because that’s as grand as your life allows. Graham: I never roleplay in role-playing games. Adam Jensen’s fist-chisels have never felt expressive to me, and I don’t feel embodied in Mr. Witcher’s scar tissue. Plop me into a game with a set of mundane verbs like It’s Winter though, and I’ll quickly start playing along. I’ll crouch on chairs to make like I’m sitting, I’ll awkwardly drag physics objects onto plates to set the table. I will imagine my character is world-weary. Best stare out the window at the mist-covered gloom to convey the turmoil of my soul. Best do a big sigh. Will this winter never end?

They Are Billions

Ollie: Whenever Christmas nears, I feel the urge to play They Are Billions. Partly because I first played it in December two years ago, just as the house was starting to smell of pine and mulled wine and all the other -ines. But I think it’s also because, despite everything, despite the subject matter, despite the moody music, and the fact that every moment threatens your demise at the hand of a pasty churning mass of several thousand undead - despite all of that, there’s something about the game that’s just so warm, so comforting. It’s like sitting in front of a fireplace. A groaning, salivating, masticating zombie fireplace. It’s strange that I can feel so comforted by a game that generally imbues such a constant sense of threat and dread into the player. Venture out in any direction from where you begin, and within seconds you’ll encounter literally hundreds of zombies lying dormant until they catch a whiff of succulent life nearby. It’s no simple matter to survive even the first 20 days out of 100, because a single zombie quietly slipping through the cracks in your ramshackle defences may very quickly spell the end for your entire colony. And that’s not to mention the enormous swarms of infected that come charging at you every so often, invariably running right towards the weakest part of your defences.

In a word, They Are Billions is hard. Brutal, even. But in late December 2017, after maybe a dozen failed colonies, I finally managed to defeat the seemingly endless final wave of undead and survive the full 100 days. And after that point, I never lost another game. No matter how high I crank up the difficulty. It seems I’ve cracked it, found the ideal formula for building an economy and defences so strong that the infected are barely able to even make a dent in the colony’s walls. And despite that, I’ve never grown bored with the game. It’s always different, and it’s always a challenge. I may have cracked the game, but that isn’t necessarily a bad thing. It doesn’t mean I now find the game easy, or unengaging. It’s that I can now play it when I want to relax. And that’s something I really value about it. Of course, this is all in reference to the survival mode which has been out on Steam Early Access for the past two years, rather than the campaign which was released (along with the game itself) five months back. I haven’t yet been able to play through the campaign of They Are Billions, but perhaps this Christmas I’ll finally have the time. I can think of few things so relaxing as sitting back one cold winter’s afternoon, a steaming mug of gluehwein by my side, and attempting to protect my colonies from the billions of ravishing, slavering undead approaching from all sides.

Mutazione

Alice Bee: So, your grandad is sick, and you travel to the island where he lives to see, and take care of, him. Except he lives on an island that was struck by a meteor decades before, and now everyone born there is some kind of mutant. Not the X-Men kind, the kind that is just a non-human looking person. Not a lot happens in Mutazione in a game-y way (I mean, you save an ecosystem I guess). Mutazione is meant to be a soap opera, so while they’re mutants that look like cats or big lizards, their drama is very familiar. Grief! Loss! Pregnancy! Your job is to listen and be a part of it. And to grow things. Mutazione has lots of areas where you can grow gardens. Different plants create different emotions, which affect the inhabitants of the little mutant island, and to progress you have to make a garden that fulfils the right feeling. A sad crop of lilies or happy whistling grasses. You can, if you want, just sit in the gardens and listen to the noises they make. I would really like Mutazione to have a infinite garden mode where the game is just you live on Mutazione and grow plants, forever. A few months ago I got a desk plant (called James Plant; gendered only so I can refer to James Plant as “my son” and thus unnerve the HR manager the plant is named after, which may actually be an HR issue). James Plant has genuinely been a massive bolster to me. On days when I don’t feel like getting up, I am moved to go into the office and check that James Plant has clean leaves and doesn’t need watering. James Plant has recently grown a new spray of young, bright green leaves, and I want to check how tall it is each day. I have secret plans to repot James Plant (the first time I have repotted anything!) and to grow new plants from leaf cuttings. I genuinely cannot recommend getting a hardy houseplant enough. Mutazione was right! It was right!

Alice0: Hello! Welcome! You are now in the middle of a harmful situation! Numerous volatile situations, even! What’s the plan, champ? You can’t fix someone’s relationship on the brink of collapse, cure someone’s loneliness, or undo the harm of colonial plundering. It’s not your place to come up with answers to everything. But you can be present, you can be earnest and honest, and you can support people if they want you to. Sometimes silence is enough. Mutazione is perhaps the only game with dialogue options where I often chose not to press matters further, where I didn’t want to wring everyone for all their stories and secrets. I wanted to know because I liked them but I couldn’t demand it. I didn’t fear rejection, I feared that these gentle people would tell me secrets they weren’t ready to share because they didn’t want to make me feel hurt. I worried a lot about everyone while playing. But you can be present, you can be earnest and honest, and you can stop deciding what’s best for other people. What a treat to explore this island day-by-day, checking in on people, planting gardens, quietly fretting, and growing friendships. Being introduced to a new pal’s secret swimming spot is the most intimate moment I have experienced in a video game. Disclosure: Some pals of mine worked on this, including former RPS contributor Hannah Nicklin.

A Short Hike

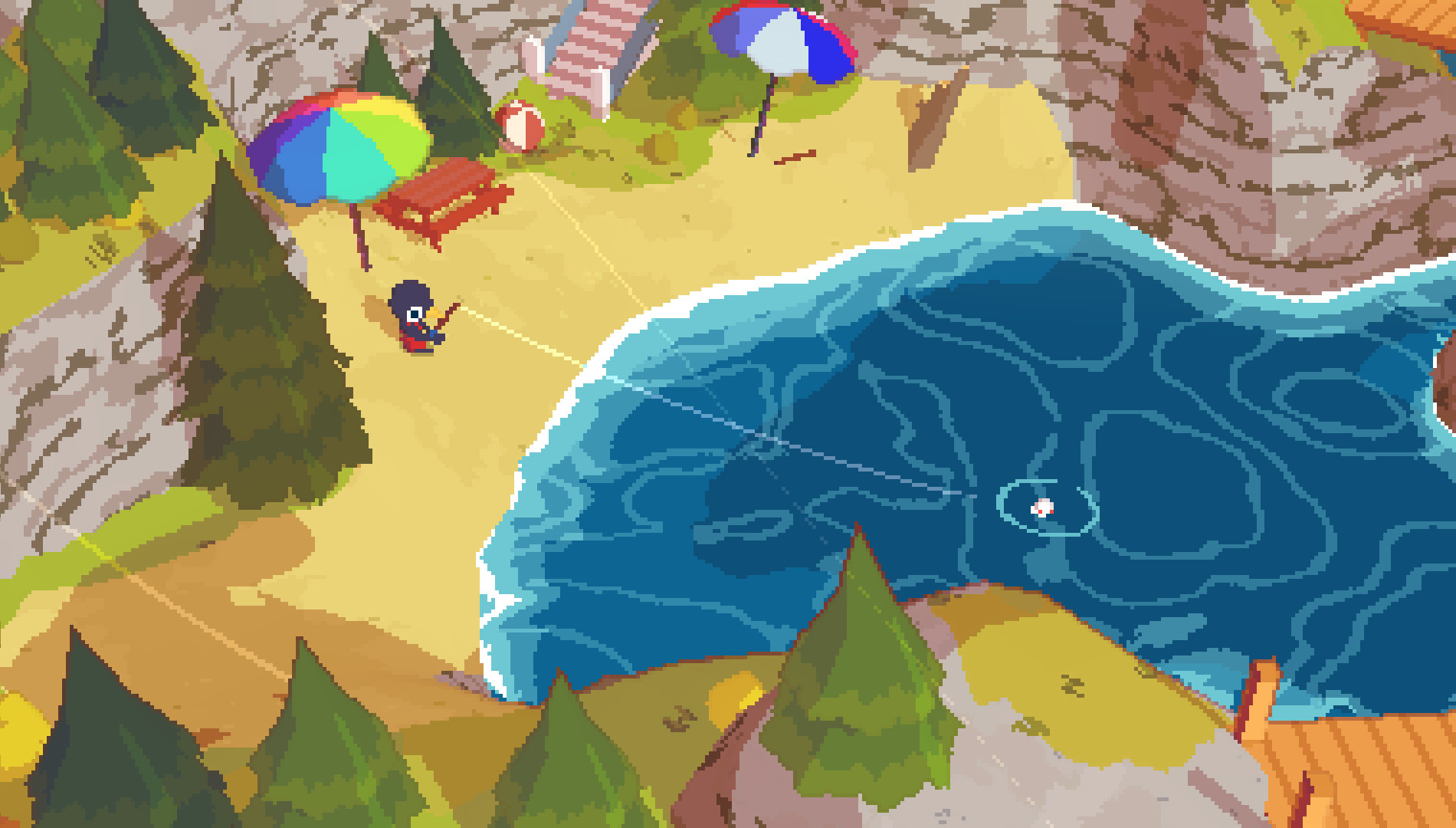

Graham: Claire, the bird protagonist of A Short Hike, is on vacation on a rural island. So far she’s spent most of her time lounging around her cabin, but today is the day she’s finally going outside - albeit reluctantly. She’s expecting a phone call and so is heading to Hawk’s Peak in search of phone signal. Claire isn’t expecting to get much from her experience climbing a mountain, and neither was I. A Short Hike looks cute in screenshots, but I thought it would be pleasant and slight. A game to jog through and forget about. Instead, it turned out to be the most delightful game I played all year. That starts with its movement. Aside from running and jumping, Claire can grapple her way up sheer cliffs and flap her wings to maintain altitude when drifting downwards, the duration of both determined by the number of feathers you’ve found while exploring. It’s simple enough, but it makes traversal feel like a Zelda game. You’re constantly poking around, looking for resources to extend your reach, finding shortcuts, and judging whether you’re strong enough to make that climb to the next area. There is satisfaction to be found in reaching the next place.

These movement systems would be nothing if the world itself wasn’t so delightful. The island is rendered with Nintendo 64-style polygons and jagged lines, but it’s teeming with detail. Flowers sway in the breeze, wind swooshes overhead, butterflies flutter around bushes, a sparkling ocean laps along the shore. Even when you stop your climb, A Short Hike’s world keeps breathing. There’s variety, too: climb far enough up the mountain and you’ll reach snow, which brings its own challenges and beauty. Then there’s the people you meet on your journey. They’re all anthropomorphic animals, and talking to each one is a delight. There’s a yelling squirrel on the beach who can help teach you to climb, a rabbit running laps to practice for a race, a salty bird who is selling feathers to pay off his student loans. The game understands that the fastest way to make a character lovable is to show them earnestly trying, regardless of what it is they’re trying to do. That’s why I love the Muppets, the characters in Miyazaki movies, and now the forest creatures of A Short Hike.

Most of those characters have optional quests. These are small and wholesome in the best ways. For example, that sprinting rabbit has lost her lucky headband and asks you to help her find it, and there’s a frog on the beach who wants a smaller spade for building sandcastles. Everyone is trying but that doesn’t mean their ambitions are grandiose. A Short Hike is short, but it turned out to be anything but slight. It’s dense, even. There are chests to find, a watering can which can turn flowers into springy jump pads, a shovel with which to dig up secrets, a fishing rod for fishing, secret shortcuts to create through the mountain… You’ll end the game’s two hours with an inventory filled with tools, and probably a handful of secrets still to find if you want to spend more time exploring. I did want to keep exploring, and once I’d found everything there was to find, I kept playing just to hang out for longer in its world. Just as Claire found more than she expected on her mountain climb, I found more in A Short Hike. It’s a spiritually refreshing videogame - and how many of those are there?

Metro Exodus

Video Matthew: Leaving the Moscow Metro should mean leaving behind everything that makes Metro Metro. Claustrophobia. Delays expected due to Nazis on the track. Oxygen-starved sorties above ground (outside of Moscow the open air is mostly fresh). What impresses me most about 4A’s latest, then, is the way it delivers everything I want from the great outdoors - namely choice of approach and a sense of discovery - but finds constant opportunities to plunge you back into the darkness. The marshlands of the Volga river give you the freedom to explore its scattered islets, but in amongst the dilapidated shacks you’ll find yourself stalked through a church by a cult of fish-worshipping zealots, or creeping past mutants as the same cult’s damp deity churns the waters below. Sometimes it’s something as simple as falling into a spiderbug nest, or noseying inside a radioactive bunker, that sets your geiger counter a-clicking and transports you back to those earlier games. And around all this, I love what a mechanical shooter it is. You’ve the returning hand-pumped delight of Artyom’s pneumatic rifle, but also a new backpack jangling with parts that reshape handguns into sniper rifles or doll up shotguns with 20-round clips. There’s something deliciously crude in the cause-and-effect of cranking air to push a ball bearing into a skull with a deadening (and endeadening) thunk. Or the crack of a sniper rifle that is so damn loud that shots I took back in February, like many of my experiences with Metro Exodus, are still reverberating now. Astrid: Rather than waxing lyrical about every good thing about Metro Exodus, or lamenting the fact that its only recurring female characters are relegated to the roles of your girlfriend who acts as both a Strong Independent Woman™ and a damsel in distress, and a defenceless mother and child, I’m instead going to talk about the train. The Aurora is an ancient steam locomotive that you commandeer from Hansa soldiers. It acts as your base of operations and main mode of transport in the quest to find civilisation outside of the Moscow Metro. As you progress further into the Russian wilderness, through frosty swamps and the scorched sand craters that were once the Caspian Sea, the Aurora gains more carriages, better upgrades, and new people who come to call it home. In a lot of ways, I think, it resembles the star cruiser venturing across the galaxy, a bit like the Normandy in Mass Effect. This beaten-up behemoth of steel and soot is a constant throughout Metro Exodus. It becomes familiar, warm, and safe. Much like with the Normandy, you leave its confines to explore vast landscapes, almost alien in how they contrast against each other. Metro Exodus’s three open-world regions: The Volga, Caspian Sea, and The Valley, each feel like they exist on entirely different planets with all their differences in culture and appearance. But you always come back to the Aurora. Between stops, you spend your time upon it maintaining your gear, smoking makeshift cigarettes, talking with the other inhabitants of the train who have become your rag-tag family. There’s something really warming about the whole thing. It’s also all a hell of a lot more palatable because the survival aspects of Metro Exodus aren’t complete arse, so irrespective of all that pretentious train stuff, which is why it has won the Least Annoying Survival Systems award.

Untitled Goose Game

Dave: Who knew that a goose with vandalistic tendencies would be the best new character in 2019? From vegetable larceny to scaring timid children, the nefarious antics of this foul fowl have provided some great slapstick laughs. And all the while it honks and flaps at your command, it stares ahead, unblinking. Untitled Goose Game takes you through the key areas of a sleepy village (allotment, high street, residential street and pub), and challenges you to check off a list of gentle yet criminal activities on a notepad. It’s a virtual to do list that makes Untitled Goose Game a very hard game to put down after the first honk. The comedy inherent in being a goose waddling off with a gardener’s hat, or hiding in a box to be smuggled into a pub, had me smiling from ear to ear throughout the few hours of play time. It also adds a refreshing twist to stealth in that being spotted doesn’t result in getting shot. Many games can be experienced vicariously through a let’s play, but Untitled Goose Game is one of those rare occasions where to understand and embrace the horrible goose, you must first become the horrible goose.

Katharine: I would like to formally apologise to ‘Boy with Glasses’. You did not deserve the things this dreadful goose handler did to you in the days leading up to the Great Golden Bell Theft of September 20th. It is with deep regret that I untied your shoelaces, honking with glee as you tumbled to the ground, falling face first into a dirty puddle, and I am full of remorse for making off with your precious glasses, thereby forcing you to buy them back off the lady in the village shop. That was uncalled for. Never again shall such terrors be wrought in the name of banging punchlines, because that, ‘Boy with Glasses’, would be a crime against your good self, and your innate wholesomeness and purity. The goose shall be disciplined accordingly, and I only hope that you can forgive these wanton trespasses against your person. Astrid: There’s a moment in Untitled Goose Game which filled me with a sense of existential horror. In the High Street, one of your tasks is to appear on the TVs in the telly shop. You have to coax out the lady working there by trapping Boy with Glasses in a phone box (Katharine might be sorry, but I’m not) after which you slip in, flick a switch, and waddle in front of a camera that is now broadcasting to all of those televisions.

I sat there, staring at this goose, honking away into a camera lens, showing the whole world its beady eyes and nefarious beak. I sat there. Staring. Wondering. Is this all I am? Just some narcissistic goose, honking at people against their will through a screen, all in a desperate bid for attention? Some pompous bird with a vast collection of bells I know nought to do with? Is this my life now? Chilling. Alice Bee: That meme about people chanting at the dentist, but “GOOSE!” instead of “TEETH!” I don’t want to undercut Astrid’s extremely specific moment of spine-tingling fear, but I think that the largest and nicest cultural impact the goose had this year was one of joy. Everyone played Untitled Goose Game and just indulged in play. All of us, at some point in the goose game, forgot about ‘winning’ the game and did something just because it was funny - because it was fun to hide and startle someone by honking, because the slappy feet and squat waddle delighted us. It’s the sort of pure, giggling playfulness that children have when you get them a big expensive behemoth of a plastic race track, and they spend the whole day having fun with the box it came in. Yes, Untitled Goose Game does have objectives. It’s a stealth game where you are inconveniencing people. It says: please steal this apple. But it also says: if you want to pull up all of the carrots in the garden and hide them in different places, you may do that too.

Heaven’s Vault

Alice Bee: Heaven’s Vault is supposedly an archaeological science fiction adventure game. You, the archaeologist Aliya, uncover the secrets of the ancient Empire that existed years ago, aided by a robot friend called Six. But really it is a language game, because the language of the Empire influences how Aliya understands it. Languages are secret and amazing things. It’s wonderful to see the similarities and differences between European languages influenced by Latin, where you can trace common root meanings, and languages like Irish. Ireland was never successfully invaded by the Romans, so Irish has very different grammatical structure and vowel sounds to, e.g., English, which is why a lot of British news readers plump for “the Irish Prime Minister” rather than learning how to say Taoiseach properly. But languages are also evolving, amazing puzzles (charted by people like Mark Forsyth). Imagine a non-native speaker having to figure out that the noise “iuno”, which can be hummed without even opening your mouth, means “I do not know.” It’s logical, then, that a game that contains an entire fictional language to decipher, even become semi-fluent in, must be a delight. The ancient, partly pictorial language in Heaven’s Vault is only part of the mystery of its universe, but it is the key to understanding it - which makes it quite an important part. It’s intimately tied to the context and history of the culture that spoke it. So, because all the little cities and worlds are connected by rivers that flow through the sky, the world for river is, sort of, “water that is up”.

Stars are “things that give off light from up”. An eye is a “thing that receives light”. “But” is “not and”. And this is based on my interpretation of the meanings! Other people read and understand it slightly differently! Brendy and I both had physical note books where we wrote down our interpretations of words and meanings. There is a plot - a mystery, involving the rivers, and the empire, and robot. But the language engrossed me for hours. Katharine: I, too, got lost in the words and language of Heaven’s Vault this year. I didn’t make a physical notebook like Alice and Brendy, but the meanings and interpretations of this strange, mysterious dialect occupied my thoughts day and night. It’s one of the only games I’ve played this year where I’ve been actively thinking about it every moment I get. The kind of game you itch to get back to, sneaking in a quick bit before work, half an hour at lunch, before descending wholeheartedly into it for the rest of the evening. It’s also probably the first game where I’ve wanted to start a New Game+ almost immediately. Normally I have to put a bit of distance between multiple playthroughs of games I really like, if only so I can half forget all the big spoilers and enjoy it afresh the next time I come to play it. But Heaven’s Vault doesn’t need that, because it’s already (sort of) built-in.

I thought, for instance, that with all the newfound knowledge I’d accrued by the end of what I thought was a pretty extensive playthrough I’d be able to breeze through the early parts of my New Game+, but no. The language in Heaven’s Vault evolves every time you play it, with sentences becoming more complex and more meaningful to give you even greater insight into its rich and wonderfully realised history. In fact, I recently found out that you can play it four times and still not see everything. That’s incredible, and considerably more generous than it has any right to be. The mystery sitting at the heart of its ancient past is an immensely satisfying knot to unpick in its own right, too. As your understanding of certain words, objects and locations change and adapt to new information over time, you do end up feeling like a proper archaeologist by the end of it, peeling and brushing back the layers of a world that’s been meticulously crafted but whose ultimate aim and purpose is always just beyond your grasp. There’s never a “wrong” answer in Heaven’s Vault. Sure, Aliya will sometimes revise her makeshift dictionary to include the “correct” interpretation of a word, but it’s all done in a very natural and organic way that never makes you feel like a fool for thinking otherwise. Instead, it put me in the same of detective boots as Return Of The Obra Dinn did last year. Rather than the game giving you a nudge or a wink or a stern raised eyebrow about which dots you should be connecting on your giant metaphorical cork board of mysteries to solve, it’s all down to what you, the player, make of it based on your own experiences of it. It gives you the space to draw your own conclusions about this curious set of planets you inhabit, and for me, that’s all I could ever really ask for.

Hypnospace Outlaw

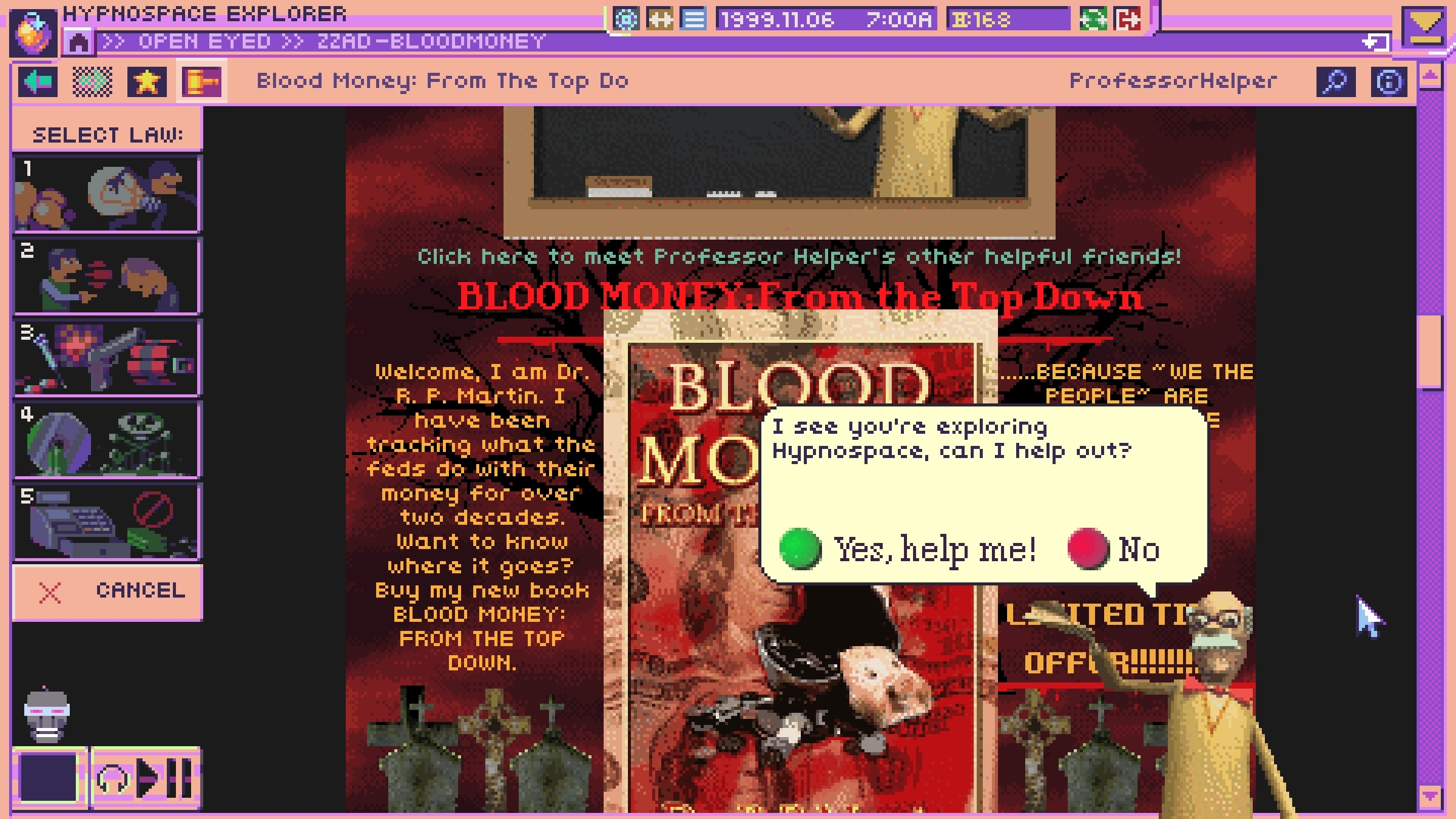

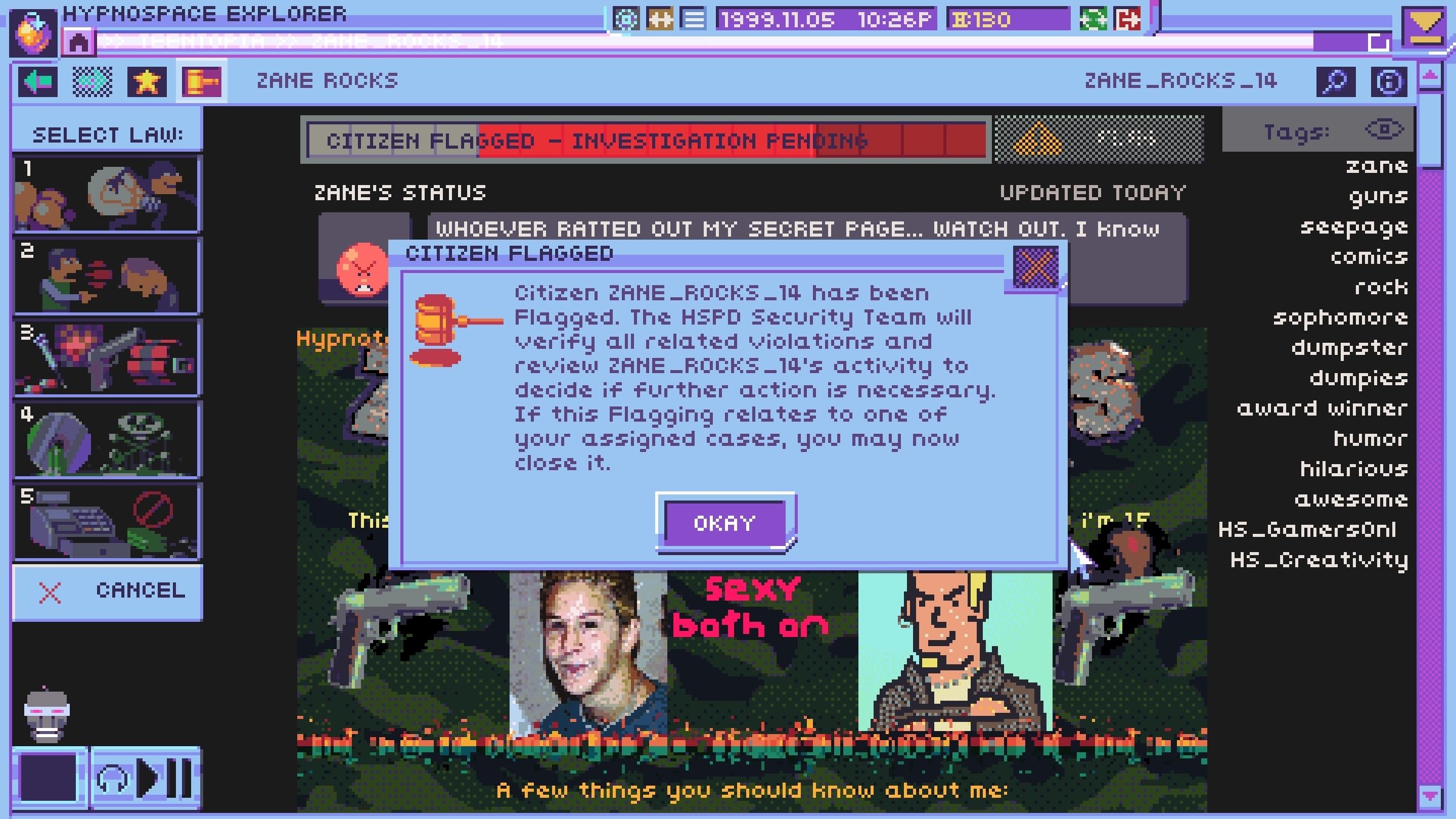

Katharine: I remember when the internet looked like Hypnospace. It might be hard to fathom now if you’re a young’un who’s grown up with social media feeds throbbing through your veins, but yes, web directories like the game’s Teentopia Paradise and Goodtime Valley were indeed a thing that happened. It was how I navigated the early internet, before Google made it all so easy/terrible by accidentally birthing the ongoing general plague and specific bane of my life known as ‘search engine optimisation’. There’s a large part of me that wishes it was still like this. Just, you know, without the mind control headbands that may or may not fry your brain while you sleep. As a museum piece alone, Hypnospace Outlaw is pitch perfect. It captures that feeling of discovering the early internet with expert precision, and rooting around its brilliantly observed user pages for naughty misdemeanours like copyright infringement, file sharing and horrible viruses was like stepping back in time. There’s such depth and personality to be found in these pages that you can almost believe this community of weirdos exists in real life, and I found myself becoming increasingly invested in the lives and emerging relationships of these imaginary internet people as the game went on. Their lives unfold so organically, too. Her Story may have popularised the central hook of searching a database to figure out the plot, but I’d argue that Hypnospace takes it one step further, if only because there’s so much more to see and investigate than what’s required to finish the main story. By giving you free rein to browse its ever-growing sprawl of internet niches, you end up discovering some surprisingly heartfelt (and at times tragic) stories rumbling along in the background, and piecing these fragments together and seeing them evolve over time is one of Hypnospace Outlaw’s greatest triumphs. Indeed, I have never seen such fervour to protect and uphold the freedoms of a goldfish detective mascot in my life, nor did I expect to feel such anguish at the loss of a past-it ‘Coolpunk’ musician. The way Hypnospace’s online denizens react to your own actions is another touch of genius. It’s one thing to see rivalries and relationships form between the people you’re investigating, but it’s another thing altogether to see them turn against you, the player, as you go about building your case files. It reinforces the idea that you, too, are having a tangible impact on this weird and wonderful online frontier, even though you don’t have a page to call your own.

Dave: I should preface my adoration for Hypnospace Outlaw by saying that I hated playing it at EGX. Playing such a heavily involved game, with such a specific interface, is not suited to an environment where a queue of people are staring daggers at your back because you’re “taking too long” to solve the puzzle. When I played it in the relative quietness of my own home, this detective game set entirely within the strange Geocities websites of the late 90s and early 2000s, I enjoyed it a heck of a lot more. Stepping into the role as a Hypnospace Admin only clicked once I was able to play at my own pace. It can get obtuse at times, particularly the part that parodies the website navigation of Neopets, but at least Professor Helper is there to help. He’s always there to help. It helps that I was one of those early nerds who tried to make a fan site in Geocities - it was based on Dragon Quest - so I, like Katharine, saw a lot of familiar things here. Sites full of cyber-bullying, pages dedicated entirely to insignificant fictional characters, and even some playing that same audio loop of Crawling by Linkin’ Park. Then there were frames. Who remembers frames? God, they were a mistake. Exploring Hypnospace was like stepping into a time machine, and one which can only transport you to swamp of teenage angst and tributes to pointless idols. It’s great Disclosure: Xalavier Nelson Jr. does some excellent freelance writing for us sometimes, and he also did some excellent writing on Hypnospace Outlaw.

Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice

Dave: FromSoftware have always done something in their games to surprise me. In Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice, that thing was this mad lad in Ashina Tower. He got a lot of us, in fairness. Sekiro is a game full of surprises, some that are terrifying and others that are empowering. Combat is very precise, more so than perhaps any other FromSoft game, with parrying and managing posture - a gauge in combat that’s roughly analogous with the poise stat in Dark Souls - making all the difference between life and death. That said, if you do die, you can get back up - provided that you have enough charge to resuscitate yourself and have another go. Does it make the game easier? No, not by a long shot. Sekiro is exquisitely crafted. It was even pleasure to write guides for it. In fact, the only thing I don’t like about it at all is the bit where you chase an invisible monkey across rooftops. Video Matthew: Wait, Sekiro has invisible monkeys? Reader, a confession: despite voting for Sekiro, I have yet to complete it. I’m still stuck on that motherfucker in the tower. Everyone tells me that this is the make-or-break point in Sekiro, the moment where you prove your grasp of the fundamentals and, in doing so, that you have the skills to comfortably face whatever is to come. Which, I’m now told, is an invisible monkey. This is not how I expected this story to go. It’s an ignoble way to end (temporarily, I hope) my Sekiro journey, which is otherwise my favourite FromSoftware game to date. The ninja fantasy is more compelling than the corpse knight fantasy or the Whatever The Hell Is Going On With The Guy In The Coat In Bloodborne fantasy. And that dash of Tenchu DNA - in the grappling ropes and stealth kills - makes linking my way from boss to boss that bit more varied and exciting. Hilariously, I’ve got a popular Sekiro tips video on YouTube, despite it ending at the precise point I’ve not yet been able to beat. That I managed to spend a very happy 30 hours in these opening areas - another fantastic FromSoft network of surprise shortcuts and interlinking cleverness - speaks to the pull of this world and its combat. Far from the sluggish stamina dance of earlier games, Sekiro asks you to push forwards and break an enemy’s spirit. Too many games pander to my timidity, and it’s refreshing to be coaxed out of my shell. Well, halfway out of my shell. Come on, don’t judge: there are invisible monkeys out there.

Oxygen Not Included

Ollie: Stinky is a dupe, one of Oxygen Not Included’s cute and almost entirely expendable worker drones. And he has a death wish. From the moment the Printing Pod schloops him out into our lonely asteroid, he takes one look at his drab, algae-covered surroundings; at his mindless clone comrades running to and fro, stuck in their daily subterranean grind; at the frankly bewildering arrays of leaky toilet-water pipes and chunky gas pipes pumping stale, recycled oxygen throughout his new home. And he decides the most sensible thing to do is to do himself in, as quickly and efficiently as he can. Which I suppose is a fairly appropriate response. But it makes my job extremely difficult. Because it means that while I’m busy trying to play Oxygen Not Included, Stinky is playing Untitled Goose Game. Or some macabre twist on it, where the goose’s eventual aim is to take its own life, and wants to cause as much irritation and disruption as possible on the way out. It’ll go like this. I’ll load up the game, pan around viewing the state of my dear and dedicated dupes, assign a few new tasks, and unpause the game. As the cycles pass, I’ll watch my workforce toil away tirelessly: let’s say they’re creating a new coal generator array, in the dark and dangerous ice biome below our base. After a while, satisfied with progress, I’ll pan upwards to check on the habitation levels, only to find Stinky standing at the very bottom of our clean water reservoir, seconds from drowning and looking extremely happy with himself. I’ll set the base to red alert and order a ladder to be built, but it will, of course, be too late. Stinky will keel over, eyes crossed, his mission accomplished. I will sigh and reload, like a weary skynet hitting the time travel button once again. This time, I will avert Stinky’s drowning. Within a few cycles, however, Stinky will have pissed in that very same water reservoir (despite the toilets being right fucking there next to him), and gotten his head stuck in the ceiling. His body will jerk and his limbs flail like a demented puppet, as he asphyxiates inside the roof. Red Alert! Someone dig out that block! But it will, once again, be too late. Stinky will always be one step ahead of me. He’s smart. He’s resourceful. And he’ll always find a way to die. Nate: Hi, my name is Nate, and today I would like to talk to you about gas, if you’re not too busy. Please may I come in? Thank you. I learned loads about gas at school. Mostly from smashing back dozens upon dozens of hard-boiled eggs, then wrenching out non-stop, face-purpling arsebarks in the grim confines of the changing rooms. Only joking! I was actually very fragrant at school, and only did a guff for the very first time when it became legal to do so at the age of 21. No, silly billy. I’m talking about chemistry, of course, where I learned that there are three big laws governing the behaviour of gases - Boyle’s law, Charles’ law and… the other one. That’s the problem, you see. I spent most of my chemistry lessons chatting with my mates Chris and Greg, and surreptitiously drawing images of our teacher’s head on the body of an enormous brute with a minigun instead of an arm. We did whole comic strips about him, which I seem to remember culminated in him hurling the entire universe at his son (whom he had constructed from pure potassium), in rage over the fact his creation wanted to live a peaceful life. There was one amazing time where we didn’t realise he was standing right behind us as we drew, until he asked us - perfectly affably - what we were doing. Deciding honesty was the best policy, we went ahead and explained the whole plot to him. “Well, sir, that’s your enemy - a giant bear with army medals - and as you can see, you’re assaulting him using the planet Saturn as a weapon.” In a move that gained our unending respect, he responded with a mild, carefree laugh, and told us that if we didn’t get on with the work that had been set, he would throw us into the sun. So yeah, I remember that, but not really the gas stuff - like eighty percent of my chemistry knowledge, it was crammed into my head during a sleepless week in order to pass my A-levels, and then fell out of my head again immediately afterwards. I think it was something about pressure and temperature and volume and that? Anyway, once I’d left school and it became clear I wasn’t going to end up working in the sciences, I didn’t feel too bad about having forgotten it all. I mean, really, the laws governing the behaviour of gases weren’t really going to come up much in non-gas-related professional life, were they? And certainly not during leisure time, unless I developed some really exotic hobbies. In 2017, however, it seemed I was about to be proved wrong. Space colony simulator Oxygen Not Included had just arrived in early access, and what was it about? Non. Stop. Gas. Carbon dioxide, chlorine, steam, hydrogen, methane: gas for days, mate. It even included oxygen, despite the assurances of its title. The game modelled everything about them, including - to my horror - their pressure, their temperature and their volume. Looks like my youthful hubris had finally come back to bite me on the arse, and I was going to suffer for my lack of gas knowledge at last. Luckily, like any good Christmas tale (gaseous or otherwise), this story has a happy ending. Because it turns out that while Oxygen Not Included boasts an extremely deep, internally consistent simulation of materials, it’s one that runs almost entirely at odds with the real behaviour of these substances. I would not, it turns out, have to know my Boyles from my Charleses to be able to build a functioning asteroid settlement after all. Nevertheless, I would have to learn an entire new set of physical laws, invented by a Canadian game development studio, and which could never prove usable outside the context of playing Oxygen Not Included. There is a certain irony, then, to my dismissal of A-level gas knowledge as something I would never need, given that I would end up putting more work into learning and memorising an entirely pretend version of the same thing, which was somehow even more useless. Video games!

Streets Of Rogue

Astrid: Streets Of Rogue is one of my favourite rogue-adjacent-ish games. In many ways, it’s the closest thing to a tabletop RPG I’ve played in the digital realm - at least in terms of how open-ended it is. I also like it because, as a smoker, it allows me to exist in a world where the addictive substance that chains me down doesn’t produce any negative side-effects whatsoever. I went on my first ever (voluntary) run outdoors recently, and I somehow managed to do a whole 5km, admittedly with a few breaks. I’d never have expected to be physically capable of such a thing, and it seems that neither were my lungs. I couldn’t stop coughing for two hours. Probably because of all the smoking. I can run forever and ever in Streets Of Rogue, though, no matter how many smokes I choke down. Just imagine how unstoppable I would be. Sin: I don’t have a favourite genre so much as a favourite… ethos? Principle? Style? Well whatever it is, it’s when a game has enough structure and content to sustain itself, but also lets you dick around however you like. Not a sandbox filled with sand (which, let’s face it, lets you do one, maybe two things) but a game that lets you rummage through a shed full of toys and then out into the whole playground to see what you can do. It’s generous, showering you with items and in-game currency to unlock more goodies and mutators. The given characters already make for lots of playstyles, even before you start creating your own. That too lets you go wild, ignoring balance if you like. It could use more variety in objectives, true (although there’s a mutator that lets you ignore them anyway. Or replace permadeath with a 3 lives system. Or make everyone look like a gorilla). But something about the opening track of its first level cries out to me with a gleeful “Okay now… go!”, and everything from there is irresistible. Of course I’ll snatch the gun and truncheon right out from a cop’s inventory. Of course I’ll hack into that cloning machine. Of course I’ll play as Black Dynamite and summon his friends to smack a drug dealer through a building. It’s the fluffiest, laziest writing to say that Streets of Rogue is “just fun”, but that’s invariably what I end up saying about it. It’s simply a joy every time I play it. Nate: I’m totally with Sin on the music. Even though I’ve not played the game since we Couldn’t Stop Playing it that one time, I still sometimes find myself doing the first level tune to myself under my breath when I’m trying to get really pumped up for something. In retrospect, I think the thing I liked most about Streets was how utterly relaxed it was about the whole concept of balance. It seemed to be well aware that some ways of playing were always bound to prove massively more successful than others, and it was absolutely fine with that. And it’s not like there weren’t a ludicrous number of things you could do to make things harder if you were finding it too much of a waltz, so I was absolutely fine with it too. I think, when you’ve got a game with as many interacting systems as this one, it’s the right approach to take. I can only imagine the horror involved in trying to fine-tune the balance of such a machine, when failing to account for any one of a hundred variables could lead to unforeseen emergent chaos. Better just to take the approach of throwing new things in at any old power level, seeing what happens, and then maybe throwing in some more wildly powerful elements, if you feel it still needs levelling out. A bit like cooking when you’re shitfaced, I suppose. Unforeseen emergent chaos was pretty much the whole USP of Streets of Rogue, so I’m glad it wasn’t more carefully thought through. If it had have been, I might not have been able to annihilate so many apartment buildings while temporarily being a giant gorilla. And that, after all, is what Christmas is all about.

Mordhau

Matt: Mordhau is silly and sublime. It lets you ascend to great heights of swordplay, heights that loom larger than any sword swinger of yore. These heights are also filled with bare-chested idiots pretending to be boxers. Heads roll, torsos crunch. Each grizzly detail, every meat sound, sells the fantasy. I once decapitated two people at once and shrieked. Spectacle lures you in to Mordhau’s combat, but finesse is what makes you stay. Techniques are myriad and subtle, more about mind games than precision or even speed. You survive by being unpredictable, constantly mixing up moves, lunging when and where your opponent least expects. It’s intoxicating, whether you’re submerged in the purity of a duel or the audacity of a fight where you’re outnumbered. The highs are higher when you win those fights. It’s easier than you’d think, too, once you learn how to exploit people’s arrogance. The trick is to play with people’s attentions, deliberately looking away in order to lure them into surprise counter attacks. When it works you feel like a movie superhero, imbued with psychic battlefield awareness. Those moments are ecstatic, but I might not pursue them if failure didn’t always feel like my fault. That’s what keeps me coming back. After every death, I immediately know how it might have been avoided. My head needn’t have rolled if I’d ducked. If I’d been smarter, or more aggressive, or come up with a better plan. It’s fundamentally different to being shot at by people with faster reflexes and better aim, a competition where the result hangs in the moment rather than years of experience. I still have to play with the chat disabled, mind. I’ve never felt the need to do that in another multiplayer game, but crusader imagery has an awful tendency to draw in awful people. It sucks even more that the developers have facilitated this, at one point claiming a chat filter would be seen as “censorship”, refusing to delete a racist forum thread, and internally discussing a toggle to hide women and non-white characters. A chat filter is now on the way, but that will do little to help the rot Triterion have tolerated. Sin: Chivalry with wankers. Ollie: Matt and Sin have already taken all of the words I had to say and made them better; but I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention the greatest discovery I made during my time with Mordhau: the existence of Skirmish Duel servers. I was already a familiar face on most duelling servers in Mordhau by that point, but they were just the bogstandard free-for-all duels, where you could challenge anyone anywhere to a fight there and then. No structure, no narrative, just duelling. Skirmish Duels changed that by dividing everyone into two teams, everyone with one life. You’d all pair off with someone from the other team, fight to the death, and the survivors would do the same until one team was left standing. The reason this was such an incredible revelation to me was that it combined everything I loved about 1v1 duels with the spectacle and drama of larger team matches. Sometimes I’d end up as the only player left alive on my team, while five players remained on the other side. And as my fallen comrades looked on in amazement, I’d butcher my way through all five foes one at a time, and carry my team to victory. Those John Wick-style comebacks were something I’ll always remember about Mordhau. I don’t think any game has ever made me feel so powerful.

Star Wars Jedi: Fallen Order

Ollie: I think it was a mistake to replay Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice in the leadup to the release of Star Wars Jedi: Fallen Order. Sekiro is perfect. Sekiro is music and dance woven into deadly swordplay. In every way that matters, Sekiro is just a better game than Fallen Order. Except it isn’t. Because Fallen Order has lightsabers. And Force Powers. And lightsabers. I felt so incredibly torn playing through Fallen Order. I hated the fact that the excellent, engrossing combat segments were broken up by extended platforming and sliding and puzzle sequences. I hated how lethargically you’d climb walls, and how late into the game you get the upgrade which allows you to climb them more quickly. I hated the constant framerate drops. I hated that the camera would flip out at times and render you unable to see anything that’s going on. I hated that there’s no fast-travel option, and that you had to spend ten minutes platforming your way back to your ship from the other side of the planet whenever it was time to head somewhere else. I hated that the yellow tint of an enemy that previously killed you would obscure the red tint that signals an incoming unblockable attack. There was an awful lot that got on my nerves while I was playing through Fallen Order. And yet, despite all this hardship and suffering, the moment I finished the game I immediately started a new playthrough on Grandmaster difficulty. And once I finished that, I started another and 100%’d the game. And after that, I started another. Because LIGHTSABERS.

Dave: There’s a lot of crossover between what Ollie said and what I currently think of Star Wars Jedi: Fallen Order. I’m still wading my way through the first few planets, but it’s scratching the particular itch that Sekiro left. I still prefer FromSoftware’s samurai epic, and I could have done without the bloat of platforming, but Fallen Order is still very good. The lack of fast travel is a bit of a drag, but the inter-connected levels are full of shortcuts and they have the same intricately designed feel as, dare I say it, the first Dark Souls. Finding a hidden boss fight with an albino spider away from the main path remains a highlight for me. I also enjoyed the story of unearthing the secrets of an ancient civilisation, while being hunted by an anti-Jedi taskforce on the side, like. Main character Cal may have a personality that’s as flavourless as a table water biscuit, but it’s hard to claim it isn’t fun to use lightsabers to deflect blaster shots at AT-STs, or force powers to send enemies flying into walls. Alice Bee: Such cautiously qualified praise from my force bois! Not so from me, the real fan. I am still enjoying the lack of fast travel, because I appreciate the maps even more and I learn their little secrets. Oh, alright, Cal is boring. But it’s okay, because he carries his personality on his back, in robot form! Good ol’ BD-1. I think a hefty part of Fallen Order’s charm is probably carried in a big branded bucket marked, crudely, in crayon, with U LIK THE STAR WAR, but I do like the Star War, and they’ve done all the Star War bits exactly right. And listen, the rest of the charm is in cool wall running bits, slugs with the head of a big sheep or something, and having a little terrarium of alien plants on your spaceship. It’s about time we had a decent third-person adventure again - especially one where people don’t argue about it being art, or whatever. I don’t care what the meaning of life may or may not be. For now the meaning of life is: killing space fascists. Fallen Order is honest and solid, like a big ploughman’s lunch. But made out of that grim blue milk, probably, to make it all sci-fi. Also, you can give the small personality robot different paint jobs.

Apex Legends

Matt: In my Apex Legends review, I declared Apelegs “the best battle royale game we’re going to see for a long, long time.” Such hubris shouldn’t have gone unpunished, but we’re ten months on and nothing has come close. A lot of that has to do with the grappling hook robot. It’s not just about the raw thrill of mobility, and the way that hook transforms the world into a vertical playground. That’s brill, but it’s made better by exclusivity. Pathfinder is the only character that can look at the top of a cliff and think ‘I’ll have you’, then sail past and over it and into the midst of too many enemies. I have played for a hundred hours and I am still too brazen, but I am fast and I can fly. My best moments haven’t been about murder, they’ve been about avoiding it. When my pals perish, Apelegs turns into a stealth game where my sole job is to survive, recover my friends’ souls, and scarper to a respawn point. It lets me bask in the glow of a day I’ve saved, despite there being far too many kids who are far better at clicking heads than me. I rarely win fights, but I’m a dab hand at escaping them. Apelegs raised the bar for battling royally, and then it added dragons. What more could one ask for? Nate: As was the case when I wrote about the Legs Of The Apes in our best of the decade list, I’m going to start talking about how much I like it by talking about how much I don’t like another game: Plunkbat. Well, I ought to qualify that by admitting I’ve probably sunk ten times my total Apelegs play time into the battlegrounds of Mr. Unknown. Which means I can’t hate it that much, can I? Well no, I suppose I don’t. For a good chunk of 2018 it was the place where I stayed connected with a good friend, and it acted as a weird modern analogue for the long, rambling phonecalls of my teenage years. We would spend hours chatting while holed up in dilapidated Russian bathrooms, and only very occasionally would we stop shooting the breeze in order to shoot at distant strangers. More often than not, the only way anyone listening in would know we were playing a game at all would be the occasional barks of sudden alarm, as packs of balaclava-clad maniacs burst into our hiding places and murdered us in cold blood. I tried playing without my mate a few times, and while something about the Battle Royale formula really appealed to me (the initial chaos, I think - I love huge, confusing battles with many different sides), the game itself felt as cold, inhospitable and joyless as a sunday evening in February. There was, in short, not much fun to be had, besides the brief, frenzied sadism of beasting a stranger with a crowbar out the back of a ruined barn. Maybe I would have liked it more if I had been better at it. Then, as my Plunkbat phase was reaching an end, along came Apelegs. I’d just finished Titanfall 2, which had properly reinvigorated my love for a good, meaty single player FPS campaign, and so the idea of a Battle Royale game from the same developers seemed promising. Plus, hey, it was free to play, so I had nothing to lose. I didn’t know anyone else who played at the time (probably the one reason it didn’t stick with me as long as Plunkers), but even playing on my own, I had a grand old time. Where Plunkbat was turgid, drab and rough around the edges, Apelegs was fast-paced, colourful and polished - and it never went too far, into the headache-inducing hyperactivity of Fortnite. Where Plunkbat was set in a series of dismal, collapsing generic Failed States, Apelegs was painted in Titanfall’s bold science fiction hues, complete with giant alien elephant things walking around on the horizon. And where Plunkbat had zero element of character - at least beyond the occasional muffled, racist shouting of your assailants - Plunkbat borrowed from Overwatch with a fun, varied roster of space brawlers, and a pointedly diverse one at that. It was clear Respawn had hopes for a different sort of playerbase, and I appreciated that. I was no better at it than I had been at Plunkbat, mind, and without anyone to play with I did end up drifting away when other games stole my attention. But it left a good enough taste in my mouth that I keep intending to come back, maybe this time with Matt to ferry my soul around when I inevitably die. I’m happy to see the game’s doing well - while it gained the lion’s share of its playerbase in its opening month, it has at least continued to grow, with around seventy million people currently apelegging at present. That’s still barely a chimp’s shin, compared with Fortnite’s two hundred million dabbers, but it leaves me quietly hopeful that it’ll still be going strong when I eventually find time to play again.

Red Dead Redemption 2

Katharine: Red Dead Redemption 2 does many things to an exceptionally high standard. Not only does the world look incredible (especially in silly ultrawide), but it’s just so gosh darn detailed as well. For this declaration of advent joy, though, I want to give a shout out to Red Dead’s lovely, lovely horses.

They are the best horses in all of video games. Fact. They have such heft and oomph and POWER. Oh, the power! Every trot, canter and gallop feels like you’re riding on the back of a goddamn steam train, I tell you. They’re so much horse-ier than, say, Assassin’s Creed Odyssey’s weedy stick freaks, whose joints are so stiff and mechanical that you can barely even call them horses (listen, I love Phobos, but only because I can chuck him off the edge of a cliff and have him incur zero injuries as a result). Heck, even Roach from The Witcher III can’t compete with these majestic beasts. And yes, I did just 100% go there. If you’ve got a problem with that, you can find me in the town of Valentine where we shall dual with pistols at dawn.

Nate: Hey, boah! Eeeeasy there. Yerr a strawng one, aincha?

Luckily for me, I had something of a refresher course in Red Dead Redemption 2 yesterday, because I was streaming it as part of the RPS Christmas charity livestream thing (seriously, take a look - it was a right old lol). I will talk about it in a second, but first I want to share something a bit cute. While I was playing, my family at home decided to put the stream on the telly, and my sixteen-month-old daughter LOST HER MIND at the fact I was on TV, but all small and in the corner. Squealing with excitement, she ran up to the screen and tried to give my tiny face cuddles and kisses. Then, when I didn’t react to her, she started waving and shouting “dada?”. Eventually, she fell into a rage because I wouldn’t come out of the telly. Bad Dad Rejection 2 :(

Anyway, yesterday reminded me that although RDR2 is very beautiful, well-written, deep, huge and all the other things people say about it, where it really excels - for me at least - is as a strange, surreal horror game.

My favourite thing to do in RDR2 is just roam the land, with the vaguest of goals (“get to the swamp”, “find a bath”), but make sure to let raw impulse take precedence over long-term planning at every turn. I try, essentially, to let my subconscious - my Id, if you like - play the game through me. Adding spice to this is the game’s immensely complex and liquid control suite, where pretty much any button-bungling makes the cowboy do something, but it’s often not at all what you’re expecting.

I might decide it’s funny to crouch down and follow a gentleman around, holding a lantern and muttering provocations until he finally snaps and decides to fight me. But then, whoops, out comes the dynamite. Eight seconds later, I’m strangling a policeman over the carcass of a horse. What adds a real dark humour to playing like this is how unpleasant and visceral RDR2’s violence is. Smashing a bullet through someone’s sinuses from a foot away, or jamming a hunting knife into the pebbly rubber of a turtle’s neck, is genuinely harrowing - the fact it can all happen so casually, and with so little reason behind it, makes sessions play out like anxious fever dreams.

Indeed, over hours and hours of playing the game like this, I’ve come to think of the Cowboy as a sort of lost soul - a befuddled, reeking beast-man who was once perhaps well-meaning, but through endless acts of unthinking brutality, has become a kind of demon by default. He’s forever trying to wander back to civilisation, and he’ll get right to the cusp of rejoining the human race - but then he’ll catch sight of a train in the corner of his eye, and decide to chase it and skin it. The cycle of blood begins again. Lovely stuff.

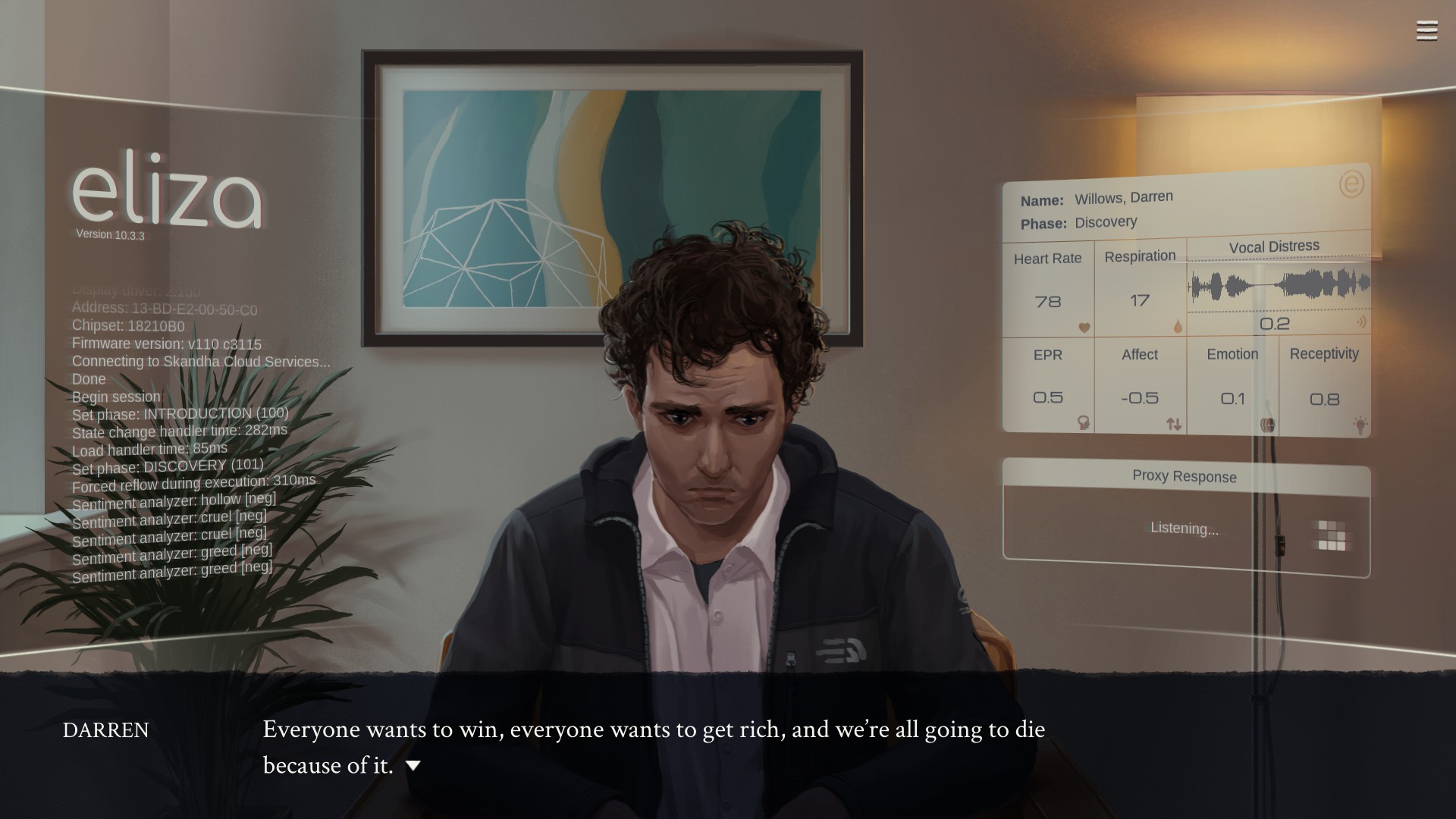

Eliza

Matt: Eliza is a virtual counselling program. You play as Evelyn, who burnt out of her tech job and now works as a human proxy to deliver Eliza’s computed therapy suggestions. At the end of the game, I abandoned my grand ambitions to change the world. Not because I thought no good could come from trying. The plans of tech giants like Soren and Rainer had their pitfalls and their privacy problems, but stemmed from a genuine and potentially achievable goal to improve people’s lives. Neither plan was truly disruptive. They both treated their treatments as stopgaps, plastering over the broken society Eliza takes great pains to reflect. They might help people with their problems, but the root of suffering lies so often in the system, and always unaddressed. It’s not irrelevant that tech stands to profit. The people you meet in Eliza have had their views and values warped by a world that doesn’t want them. Evelyn’s ability to recognise that, to provide a connection in place of an algorithm, made my final choice an easy one. It was clear which route she’d find more fulfilling, and clear that I’d never dream to deny it to her. Eliza is a game about figuring out what’s important. By the time I’d spent three hours doing that with Evelyn, I cared most about what was important to her. Sin: I’ve spent most of the last five days alternating between coping, and falling on the floor crying. I wish I was exaggerating. Eliza is about people like me. This last year or so, I’ve been like Evelyn, committing myself again to the current of the world after years of isolation and grieving. That slow, invisible process of clotting and stitching and opening fearfully up to the world that let you down so badly before. At my worst, like this week, I am like Darren. The one-off client who is simply too overcome with awareness of how terrible the world is, how bleak the outlook is for so very many people, for no good reason, to function without falling apart. Everything can be going fine but then suddenly you have to get the hell out of here, and try to run home, give up and collapse in the street 50 metres from your house, half hoping some passer by will save you somehow, half hoping you can just lie here until everything stops. I’ve often felt like Maya, the anxious artist who half believes in her work but struggles so hard to like herself that it never sticks. She reminds me of a dear friend too, especially in one conversation she has with her friend that could have been taken straight from one of our own, years ago. Once in a great while, at my very best, I’ve been like Nora. I’ve had my shit figured out and I’ve listened, and reached out, and been there to help someone else find their own way, without imposing mine on them. Mostly though, I’m like Evelyn. Lost, but marking a path. Lonely, but needing solitude. Wanting to help people, but not knowing how, and being too wounded to support anyone else anyway. It hurts to know how much more you could be doing, if only you weren’t hurting so much. But she’s getting better.

Evelyn reaches a crossroads at the end of Eliza, and it’s up to you to decide which way she goes. Most of the time when visual novels ask for this kind of decision it feels very artificial. In Eliza, it feels right. This was always about Evelyn coming back to life and deciding what to do with it. A few of the endings are, I think, deliberately absurd. There are no bad endings, but a couple are so contrary to the spirit of the story that if you choose them, it almost feels like it’s taking the piss. They’re technocratic solutions to problems that can’t be solved by inventing the right toy or starting the right business. Magic potions given a science fiction spin. But the men selling the potions are part of the problem. The other endings work for me. My dear friend Deborah went with the noble ending, in which Evelyn tries to take even more on her shoulders so she can help people. Classic Deborah. I admire that ending but I couldn’t do it. My Evelyn had been through enough. She ran off with Nora. Friends, lovers, it’s not made explicit and it doesn’t matter. It was a decision to reconcile, to bring the best of her past into a new future, with someone who cared for her. It was a decision to get better. I want to be like Nora again.

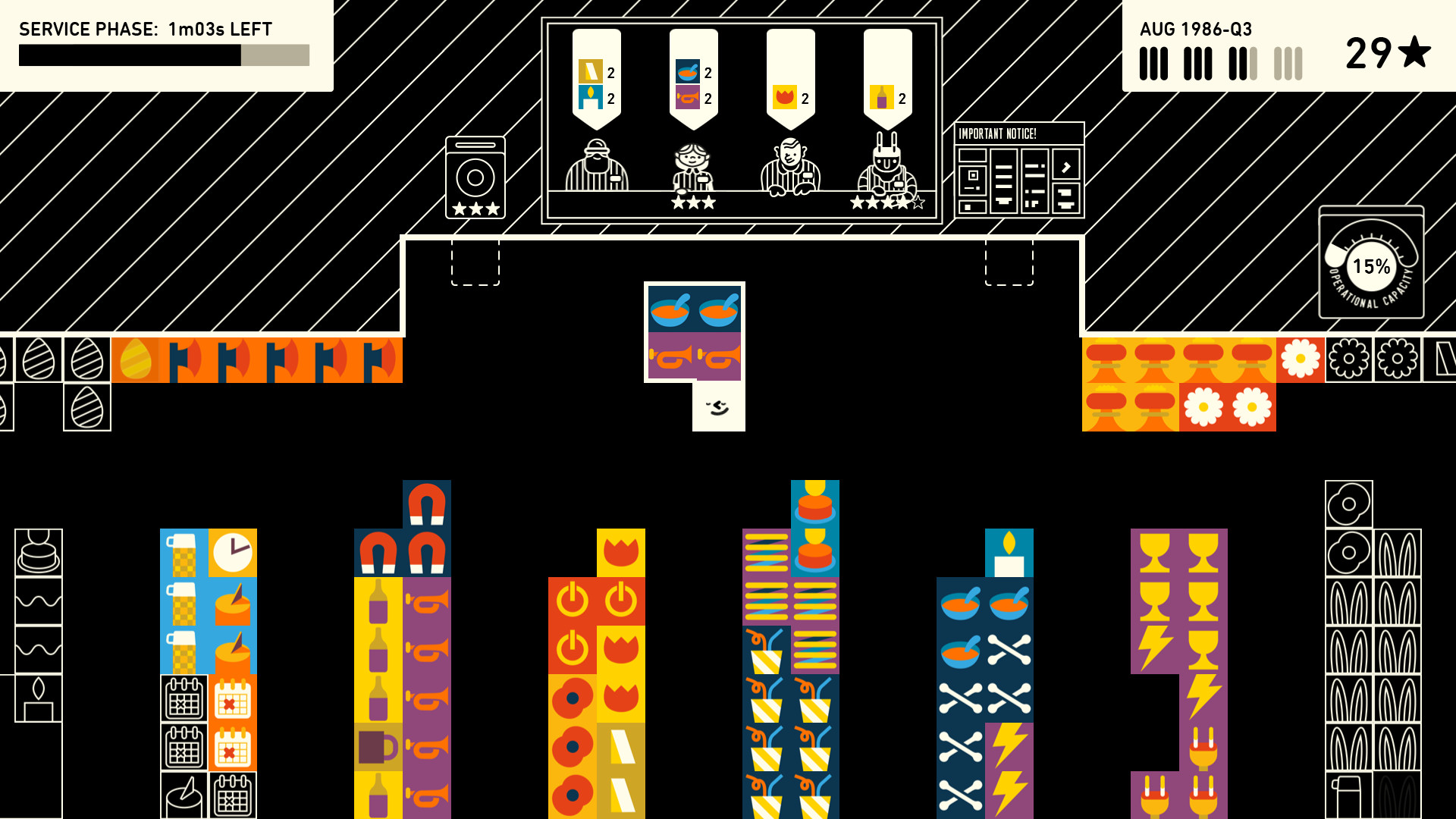

Wilmot’s Warehouse

Alice Bee: Wiltmot’s Warehouse really is a belter. I was enchanted the moment I saw the trailer (which, disclosure, is voiced by Pip, late of this RPS parish). In Wilmot’s Warehouse you, Wilmot, a happy little cube, zoom around to sort and store items, and delivering them to… customers? Other workers? Who knows. They want your stuff. How you organise your inventory is entirely up to you. Sunsets in one corner, card suits in another. A whole stack of wheels. I had Food taking up about a third, with subcategories of Food, Sliced and Food, Nuts. I kept stuff to do with politics and law enforcement in the bottom right. Ho ho. I’ve said before that playing Wilmot’s Warehouse made me think of Lyra reading the Alethiometer in His Dark Materials. I drift out of direct contact with my mind, so I can recall all the meanings I have given the blocks, and where I have put them. You can see all the different meanings each block could have, touching each other in a big ladder, all the way down. The thing is, though, that while all the items you receive are very often to interpretation (what I saw very clearly as a dog tag Brendan thought was an aeroplane window??) they do actually have correctinterpretations. I spoke to the Richard’s Haggett and Hogg at EGX this year, and Hogg (who created all the little blocks in the game) is a walking encyclopaedia of their meanings. When he started listing off, one by one, what they actually are, I felt destabilised - on the verge of an existential crisis, almost.

Dave: I knew that Wilmot’s Warehouse was going to be a big deal as soon as I saw Graham playing a preview build for well over an hour. He has great taste. It’s deceptively simple to get into, but getting into a rhythm that actually works can be very difficult. Do you sort by theme? Maybe background colours are the way to go? Stock Takes are welcome breathers where you can change your mind and rearrange at your own pace, but when new deliveries come in, and you have to fulfil orders, it’s a frantic dash, and you assign space for new stock via very tenuous connections. Everyone has their own way of sorting stuff, and it’s fascinating to hear how others do it. My partner has played loads of Wilmot’s Warehouse, because she loves micromanagement games, so it is very much her jam. I thought I knew how her brain works pretty well, but as I watched her sort, in a way that undoubtedly made sense to her, I couldn’t see any system in place at all. Ollie: Yeah, it’s a great game, yada yada. I’ve got something else to talk about. Something desperately important. Do you pronounce Wilmot as “Wilmott” (hard “T”), or “Wilmoe”, like Moe’s Tavern? My brother and I have been debating this for months, with no end in sight. Please put an end to it, one way or another. I don’t care anymore. Just let it end. [Ollie it is pronounced out loud in the first line of the trailer, this is no debate at all. - ed]

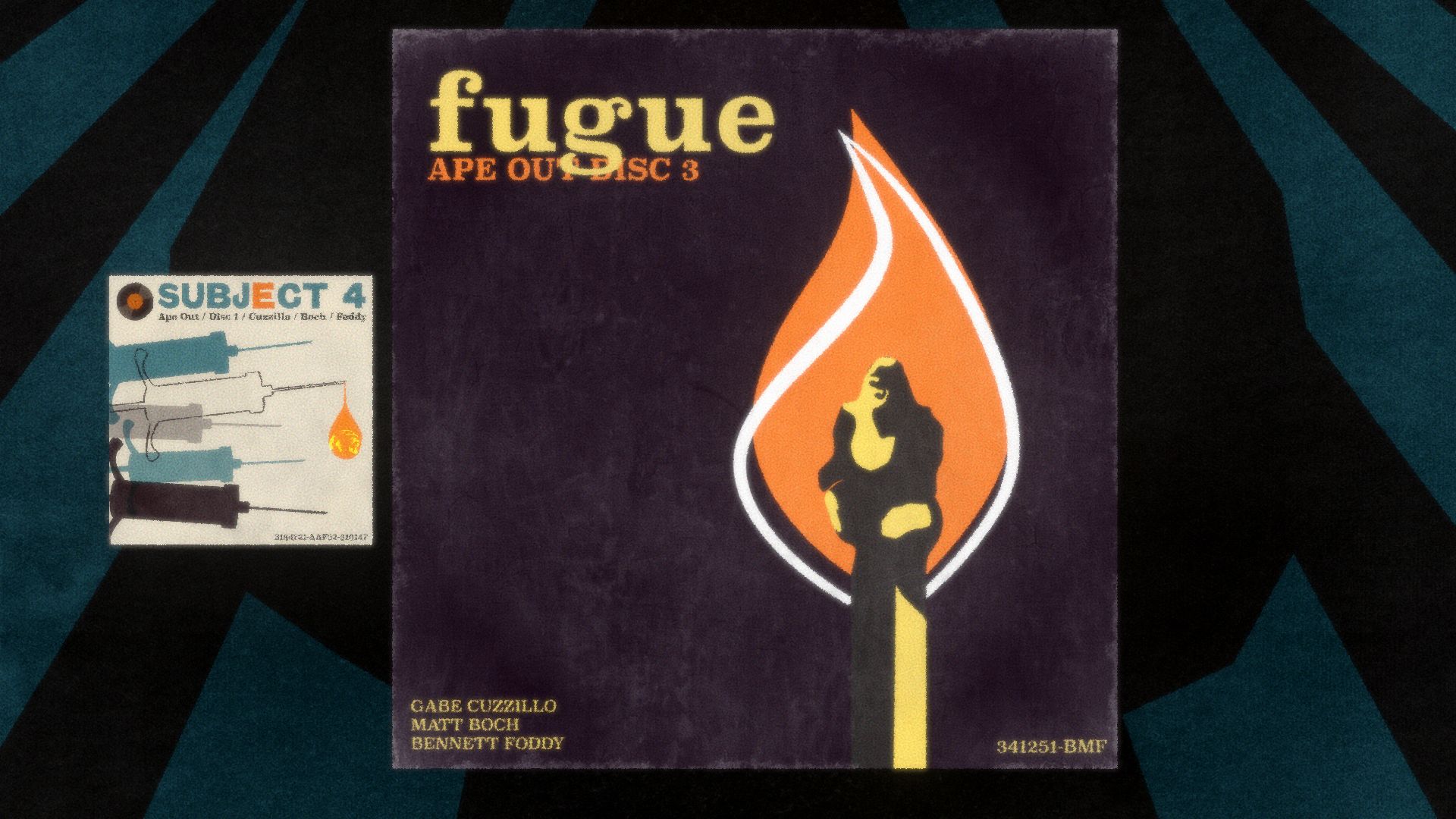

Ape Out

Alice Bee: I first played Ape Out at Gamescom last year, and, as it if were a puppy in a grim pet shop in a shopping centre complex, I was sad I couldn’t take it home then and there. When I saw it again at PAX South, I hung around the booth for almost an hour, exhorting other attendees to pick up the controller to have a go. So, disclosure: I accidentally did some unpaid PR-ing for Ape Out. In Ape Out, you are an ape, and you have broken out. You rampage through a military base, a science facility, an office block (which for some reason has stored a furious gorilla on the top floor). And, to the frenetic crashes of a procedural jazz drumming track created by Matt Boch, you get… even more out. Crash from one side of the screen to the other to escape. Splash men across the walls and floor. Evade their rockets and their machine guns. The controls are move, grab and shove - shove with your meaty, shovel-sized hands. It is a riot of colour and music, and also just a regular riot. The simplest and best endorsement I can give Ape out is that I have never before played a game that so completely achieves everything it sets out to do.

Dave: Like a lot of the games I’ve loved this year, this is one I first saw courtesy of another member of the RPS treehouse. I watched Alice Bee shove a fella with a gun out of a window, and I knew I had to play it for myself. But the game is so much more than drums and impromptu rage. It’s also intense in a way few games manage to be with any consistency. One wrongly timed shove is all it takes for an enemy to finally take you down. While your gorilla can take a few shots from most guns, they’re not invincible, and will soon be painting the floor with blood - the bigger the orange juice coloured trail is, the closer to death you are. When you do eventually succumb to the gunfire, the camera zooms out to show you the progress you made in that level. It encourages that “one more turn” mentality that seasoned Civilization players know all too well. The RPS video team played Ape Out early in the year and it’s still one of my favourite videos they’ve ever done. The absolute carnage, supplemented by the angry drum solos and with Matthew Castle pleading for a guy with a shotgun to “Get through that window, you dirty boy”. Perfection, surely?

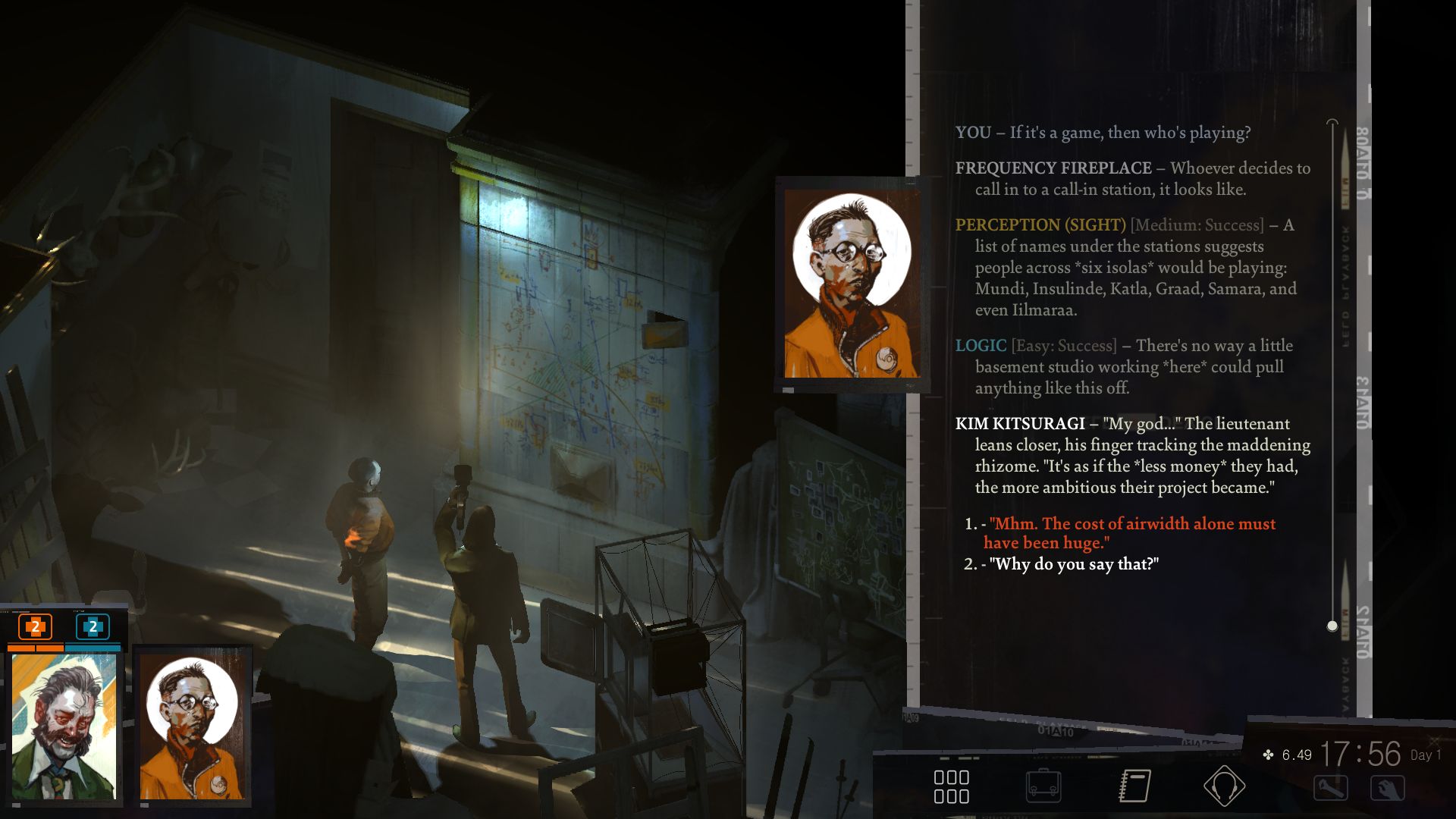

Disco Elysium

Alice Bee: Disco Elysium is an incredibly detailed RPG made by a group of the proverbial starving artists, and it probably shouldn’t exist, but by an incredible effort it does. You play a late middle aged alcoholic cop - you know the type. He was a good detective once, but his life is in ruins around him. Except, when you take control of him, he’s partied so hardy that he can’t remember who or what he is, or even where he is. The task is twofold: put yourself back together, and also find out who done a horrible murder. Disco Elysium’s skill system is a complex one, where each ability is represented by an aspect of yourself. Imagine it as all the little internal voices you have, and putting skill points into them determines how loudly they can shout. Occasionally they can override what you actually want to do. The classic example is Electrochemisty, which likes fags and booze and drugs, and can make you take them if you give it too much sway. I played as a high intelligence cop, who could use Visual Calculus to reconstruct crime scenes, and noticed small details. He hoovered up information and spat it back out at sometimes inconvenient times using the Encyclopaedia skill. But he had little emotional intelligence - his lack of Empathy meant that he could tell if someone was lying but not why they might be, unless he could cross check facts to find a logical reason. He stalked the poverty-wracked streets of Revachol with a plastic bag, so he could collect bottles and sell them and hopefully earn enough for room and board. (I imagine he was very lonely, so I worked extra hard at making friends with Lt. Kitsuragi, the partner assigned to help you on the case.)

Because of this skill system, you end up being what you think is important, in a way that no other RPG really achieves. It has a real effect on how and why you have conversations. But, at the same time, your character does have a defined past. He has a name, and he has a story, that brought him to this point of a complete and total breakdown. He is intensely masculine, and intensely middle aged, and that is perhaps why I didn’t relate to him like our Alec did. It is destined to be one of those games - the ones with 20 thousand word essays written about them on subreddits, the ones that are part of the PC canon, the 25 games you must play if you’re a real PC gamer. It’s an extraordinary achievement, really. Astrid: As a self-aware Communist, Disco Elysium makes me feel simultaneously mocked and emboldened. I’ve never played an RPG where I’m able to comment on every instance of worker oppression or societal injustice in the same way that I do in real life. Equally, I’ve never played an RPG where these words were then called out for what they often regrettably are in the first world of the 21st century: empty. Throughout your investigation, you encounter ruins left behind when the Communards of Revachol were slaughtered, and the remnants of those who still carry the ideology, and if you explore them enough you can internalise it all and decide to become the (self-described) Last Communist. The world has truly gone to the dogs in Disco Elysium, though, and rarely do you feel hope as the Last Communist. But at the very least, the Communists in the world of Disco Elysium had an absolutely banging logo, with an inverted star that represented the toppling of the old order, and antlers as a natural crown. It’s cool as hell.

Video Matthew: Not enough credit is given to Disco Elysium as a detective game. The crimes that set events in motion won’t necessarily wow genre fans, but the underpinning RPG gubbins provide a surprisingly sturdy skeleton for a procedural. The cycle of beefing up your character to return to (and pass) failed skilled checks gives each location more layers than an onion, peeling back vague assumptions as you get ever closer to the truth of the matter. A bedroom can be a bedroom the first time you visit, a crime scene the second time and a very different crime scene the third or fourth, all based on the wits of the detective who walks through the door. I’m also dazzled at how the game’s side quests, an initially daunting web of baffling asides and nuisance detours, gradually coalese into the central mystery. A journey into a haunted basement becomes a vital step in maintaining crime scene integrity. A mysterious blue door reveals a dramatic new perspective on well-trodden ground. Two aging soldiers argue over a game of boules, and maybe identify a murder weapon in the process. Everything exists on its own terms, painting a vast, detailed portrait of the city of Martinaise, but it all comes back to the body in the tree. In this town of a thousand stories, everyone has blood on their hands.

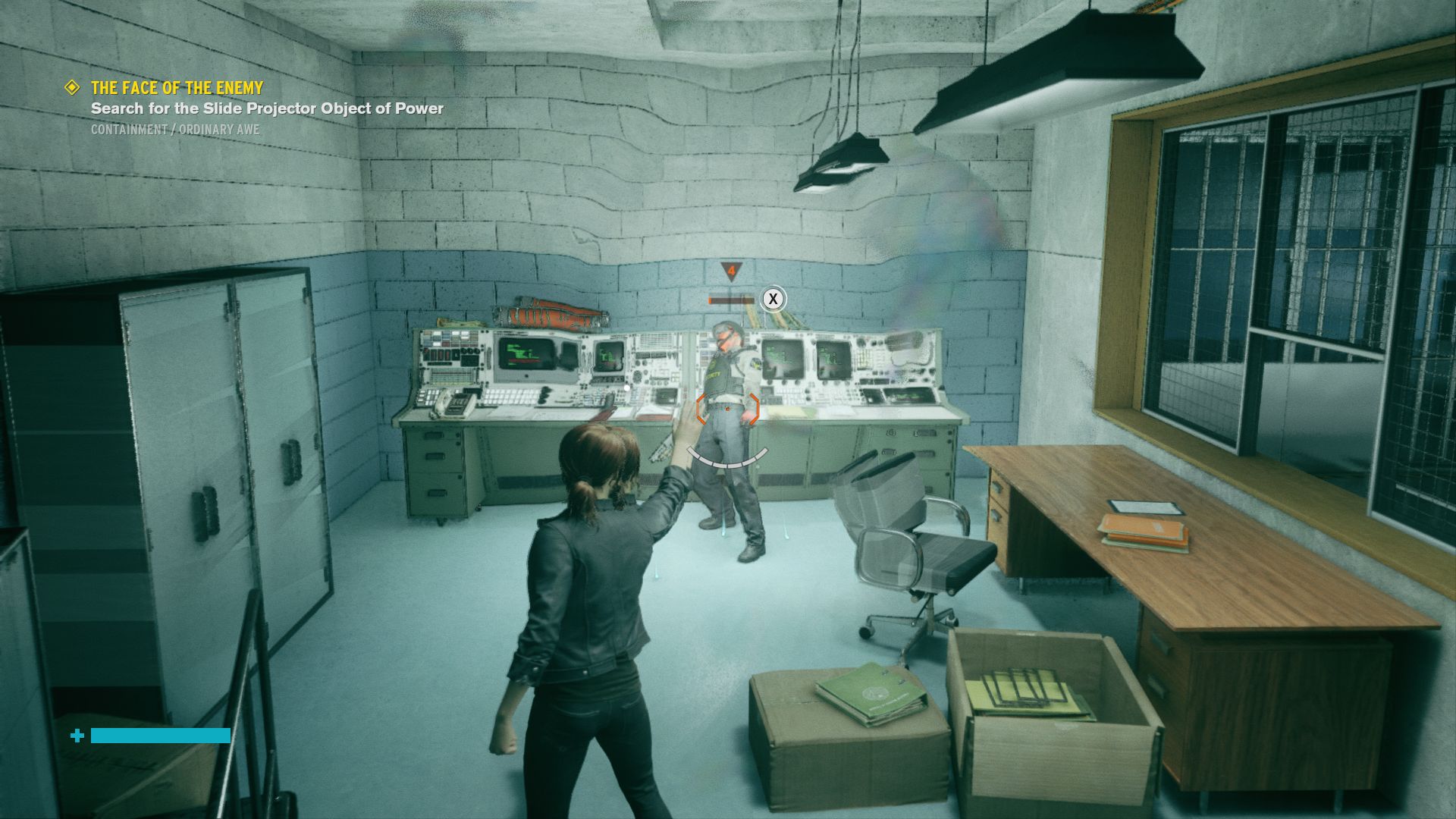

Control

Astrid: Control is like if SCP (a community-driven fictional archive of anomalous entities) and Twin Peaks (a David Lynch-directed television show about a strange and supernatural town) had an incredibly weird and wonderful baby. You’re Jesse Faden, victim of the unusual Federal Bureau of Control’s obscure meddling, and now its new Director. Your mission is to eradicate a sinister and existential force called The Hiss from the walls of the Bureau’s headquarters, an ever-shifting, dimension-bending building called The Oldest House. The FBC is an organisation with tenuous ties to the Government which is dedicated entirely to identifying and containing Altered World Events (AWEs) and Objects Of Power, all paranormal in nature. Control’s world seems to operate on the logic that everything analytical psychologist Carl Jung said about the collective unconscious, para-psychic phenomena, and synchronicity is literally correct, and the way the game plays out is as bizarre as you’d expect of such a concept. You don’t need to dive into the deep end in order to enjoy Control, but the option for you to do so is welcome. That’s what I’m doing, in fact. As well as thinking about hypnagogic film-making and colour theory, I’m also reading Jung’s works, taking that research into my experience with the game, and using it to pull on any pretentious threads left dangling about the Brutalist halls of The Oldest House by Remedy Entertainment.