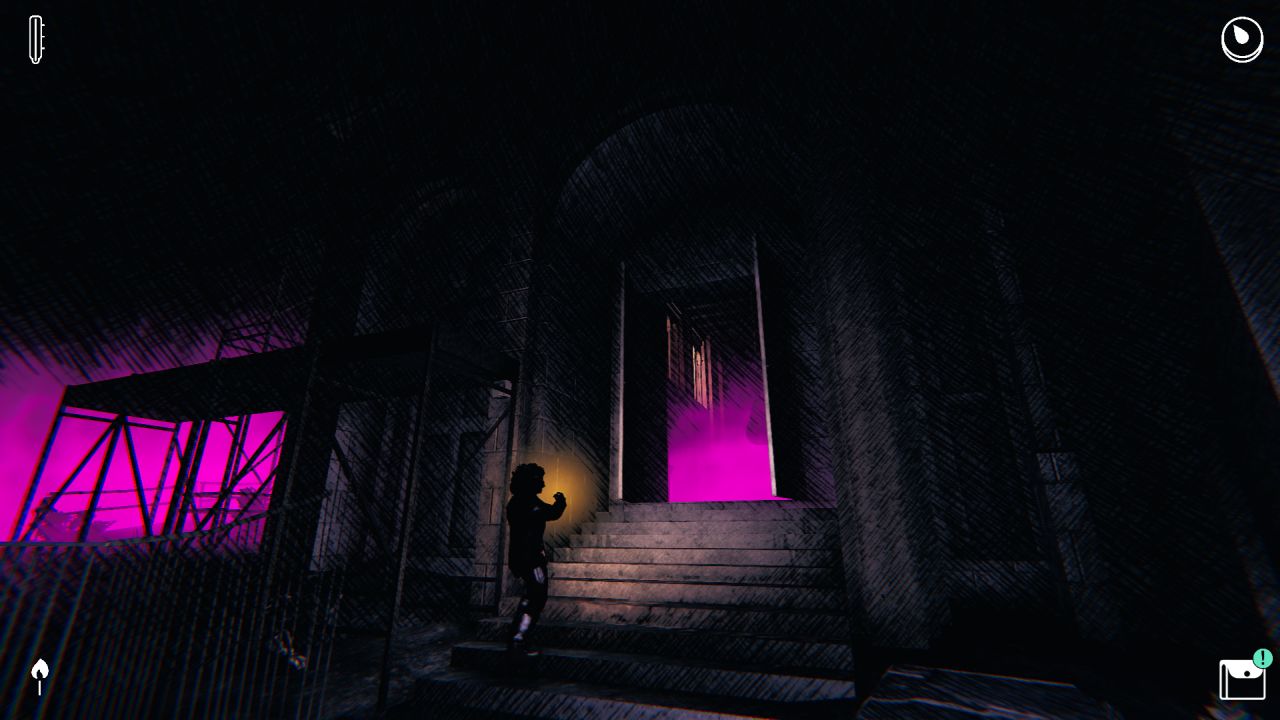

This is relevant to my thinking about Saturnalia, an upcoming survival horror game by Italian studio Santa Ragione, where a small group of outsiders try to escape a village on the night of an ancient ritual. I’ve been playing a preview build of Saturnalia for the last week or so, and also got to talk about it with the studio director Pietro Righi Riva. “I usually tell people, ‘Oh, you should make a game in like six months’, and I have tried to do that in the past,” he tells me. “This one just kind of got out of hand. I found an email yesterday, as I was looking for finishing the credits, about me discussing some story items in April 2017.” And, while I am sure that most developers don’t wish they’d been making a video game in the middle of the pandemic, I think the extra time may have allowed Santa Ragione to make something excellent. In Saturnalia you play as four different outsiders who are all in a small, fictional Sardinian village called Gravoi for different reasons, struggling with different problems. You start the game as Anita, for example, who was conducting geological research in the town’s mine, but also picked up an accidental pregnancy from a married man, while Paul was adopted and came to Gravoi to track down his birth parents. They all find themselves, unfortunately, still in Gravoi during a winter festival where people who don’t fit in are sacrificed. In response to this you are armed with a box of matches and the ability to run away through the maze-like streets. “It has changed radically,” says Righi Riva, explaining how Saturnalia was, at first, a sort of first-person mobile game in a geometric maze, until they started reworking one thing after another. “It was a very intense process of rewriting the game. And every time just holding on to the things that we felt were the most special about it,” he explains. “It really evolved in a very experimental, iterative way, in a way that we hadn’t done before.” In Santa Ragione’s previous games, which had a much shorter development time, they came up with an idea and polished it and made it work. With Saturnalia it was, says Righi Riva, “more like letting the game stick to you and seeing what was best about it.” It does stick, still. I like horror, but I’ve not been delving into horror games as much recently. Films and books run the gamut and back again of sub-genres at a dizzying pace, but the horror games I get emailed about, or find when I go looking, seem to broadly fit within three categories at the moment, these being: 1) things Protestants find most intense about Catholicism; 2) a matriarchal figure in this now-haunted house had a really bad time; and 3) this (very NSFW) Oglaf comic. But when you see Saturnalia for the first time, when you boot it up and hear whispering strangely, intimately close to your ear, you know that you haven’t played anything like it before (Righi Riva talks about finding new ways to do things in this interview with the lovely Donlan at Eurogamer, which is probably a better interview becase Donlan has read Calvino and I have not). Gravoi is dark - so dark you can’t see more than a few steps in front of you, most of the time - but the game isn’t. It’s full of a strange neon-pink mist, buildings may have bright aqua windows, fires are yellow. The presskit refers to it as “neon-folk”. Saturnalia was influenced by giallo movies, and Righi Riva cites Mario Bava’s Blood And Black Lace as a particularly clear example of the look you can see in Saturnalia. “They have this very unrealistic lighting that is super saturated and kind of, like, covers the natural colour of things. It brings us back to expressionism, really. German expressionist theatre and these giallo movies, they have in common building this theme that doesn’t look real at all and yet conveys so much emotion. We took that lesson to heart, so much so that in Saturnalia, the entire game is black and white,” he says. He explains that there is no colour in the textures, so all the colour - the otherwordly neon - is applied through lighting and post-processing. “All these different shades and different colours that exist on the characters and the buildings, they’re all added sort of artificially, and without taking into consideration the colour of the actual things that populate the scene.” Righi Riva is quick to give credit to art director Marta Gabas here, who he says was “not interested as much in level design as she was in framing these situations that could happen - well, I guess it’s another way to call level design, really.” They wanted Gravoi to convey meaning first, rather than being designed for specific gameplay situations. And as well as drawing from different architectural styles and stage design (Righi Riva references Italian architect Carlo Scarpa and Swiss scenographer Adolphe Appia), Saturnalia takes a lot of inspiration from real life Sardinia. The Italian Videogame Project put Santa Ragione in touch with the Sardinian Film Commission, who took them location scouting as if for a movie production. Gravoi isn’t a real place - both practically, because it needs to be a certain size, and out of respect, to not cast a real village as a horrifying place - but it’s based on the material collected on that trip. The masked creature that intermittently hunts you through the town is also inspired by the Mamuthones, masked figures that are part of pre-Christian carnival traditions in Sardinia. Like The Burryman, nobody seems sure of their origin or meaning. But again, Righi Riva quickly points out, Saturnalia’s village is another village that does things in a different way. The creature in Gravoi has it’s own mask, different from any you’d see in Sardinia - though Righi Riva excitedly shows me a copy of the one from Saturnalia that was made for them by a real mask artist in Sardinia. “It fits within the frame of all these stories and folklore around these masks, there’s just one additional mask in that constellation of traditions that are so varied and so ancient,” he says. “I mean, it’s called Saturnalia, because the ritual at the core of the game of the Winter Solstice is a ritual that has persisted through culture and generations and the different religions that have inhabited the island.” Really, the monster is a kind of physical representation of the actual threat. “The horror at the centre of the game is not so much the monster, the creature, but really the way that the tradition is used to suppress change and maintain the status quo, and what people are willing to do to achieve that,” explains Righi Riva. Certainly the monster can be easy to escape if you run, find a hiding spot or, if all else fails, crouch in a corner and wait for the bells to pass by. But then you realise that, because you ran away in a panic, you’re now lost in an unfamiliar corner of Gravoi. You’ve no idea which way the pharmacy is, or the entrance to the mine, or the church. There’s no map menu, you see, and though your characters can memorise the general direction of a location, you don’t get a specific route. If the creature does catch all four of the characters the town rearranges itself like a dark kaleidoscope, at once familar and unnavigably strange. Righi Riva says that continually play testing the town, and the navigation cues to explore it, as “a very delicate and dangerous thing”, even checking - with some genuine anxiety in his voice - that I wasn’t finding playing the game too frustrating so far. One character can remember places she’s been, or you could risk double exposure to the creatue by having a companion take you directly to the location you need. “All those little things are kind of ways to solve a problem that would be much easier solved with other traditional navigation, but would destroy the game.” Though they have worked hard on accessibilty, something that Righi Riva says he’s very proud of. As well as a dyslexia friendly font, there’s a mode where you can pick a destination and automatically walk to it. It’s not intended for the majority of players to use, but he says “we give you that chance to enjoy the game in a different way. It’s a cool thing that I’m that I’m very happy with.” In general Saturnalia is hitting a sweet spot of difficulty that I wish more games, horror or not, would at least aim at more often. There’s no map, no floating quest markers on the HUD, and the quest log is a non-traditional web of things you’ve found and seen, linked together by character importance or theme in a way that must have taken ages to plot out. Early on you discover you need a bolt cutter, and your character thinks, logically, that they could maybe get one at the hardware store, so you must try to find it in the inky warren of Gravoi’s streets. You can use rarely-found coins to get a fresh box of matches, or maybe fire them into a wishing well to see what happens. It’s such a horrible gem of a game. For the preview I was playing it in stretches of half an hour at a time, because I got too freaked out. You could be trapped in Gravoi’s turning streets forever. It feels like, though it was made recently, Gravoi has always existed. Saturnalia doesn’t hold your hand, it beckons you. Its long languid fingers reach out of the shadows, before pulling back just a little further as you approach. And oh! Oh! It’s dangerous! But you want to meet it! “It’s funny,” says Righi Riva, “because even like opening that email, there are some some thoughts that are still there, since then, and it’s kind of like, ‘Whoa, I didn’t remember we thought about this so long ago.’”