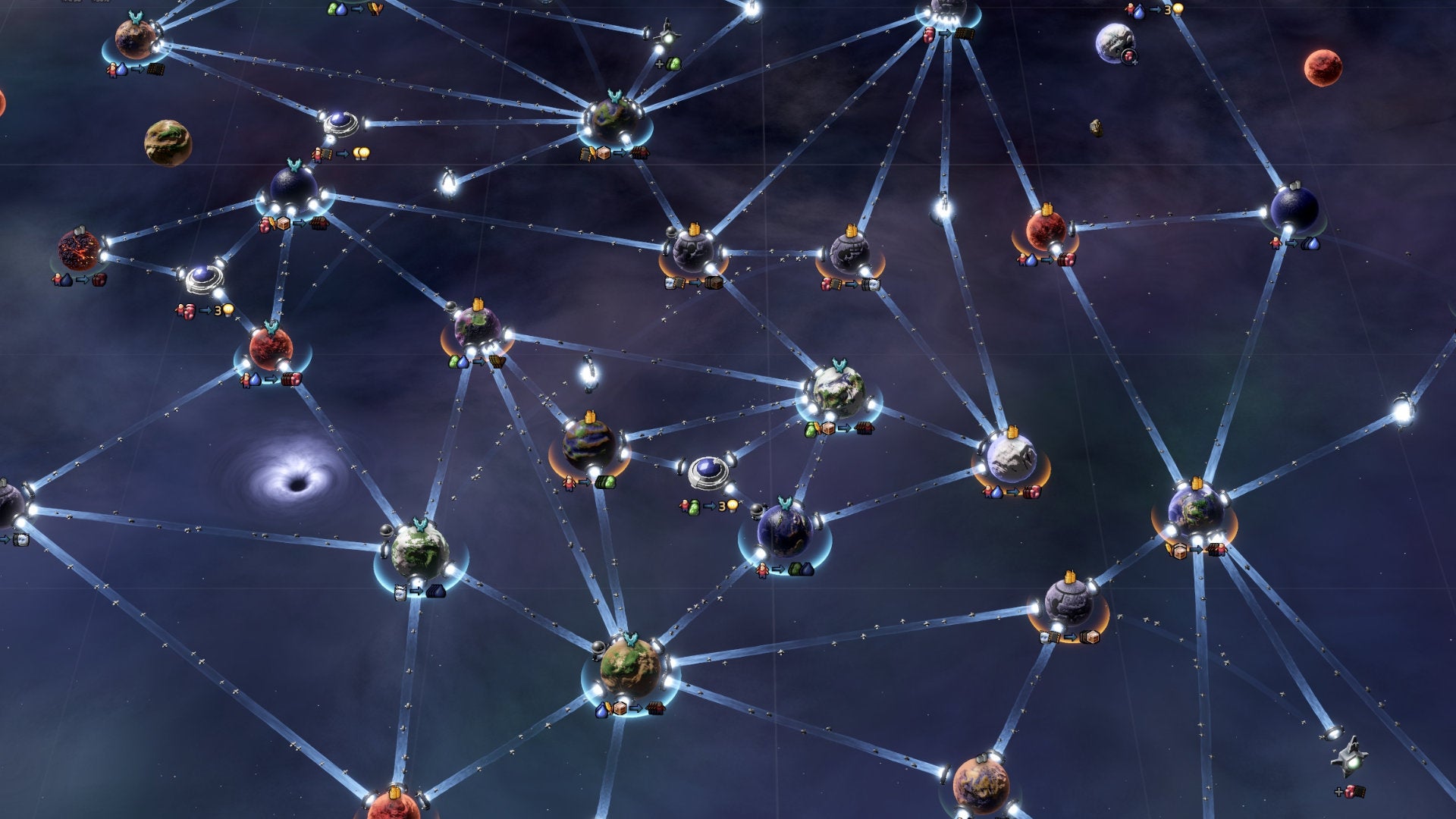

It’s the connected planets of Slipways! Matt Cox: I suspect that most humans, in the right context, enjoy organising stuff. That pleasure of hammering order out of chaos, of puzzling out an object’s optimum positioning, strikes me as something of a universal. It’s a wonderful way of exerting your influence on the world, of proving you can demonstrate that needful ability to take something and make it better. Slipways is about growing and organising an increasingly interconnected empire of space marbles, and it is glorious. You start off with a blank slate, the planets that will become your playthings just silhouettes against the void. Each one must be explored, with care taken to catch as many as possible in the pulsating circle of each probe. Probes cost time and money, and you’ll soon be short on both. Probes are a welcome touch of light resistance, some friction before the real thinking begins. Your goal is simple, really: every planet has certain resources it wants, and certain resources it exports. Your job is to join those planets up in a way that leaves no world in the lurch, while avoiding painting yourself into a cosmic corner - because once you’ve connected two planets with a slipway, nothing short of ultra-late game tech will let you cross that line. It’s all about getting the most out of what you have and what’s on offer, carving order and profit from a self-woven web of tensions. If you leave a planet without imports, its denizens will drag your empire down into score-sapping unhappiness, or even into a game over screen. If you expand too quickly without a healthy core of interplanetary trade, you’ll go broke. If you ignore the tasks set by the space council (colonise different types of planets, establish specific trade routes, produce half a dozen robots), you’ll squander valuable rewards that can springboard you into further success. And if you don’t take the time to pursue the all important tech tree, you’ll never get the chance to flourish before 25 years have passed and your reign abruptly ends. That time limitation is important, because it prevents the game from bogging itself down. Each run takes between 45 minutes to three hours, depending on how much you enjoy extended marble mulling. I like to hover over every decision cluster for a good while, testing out different possibilities using the exemplary and forgiving UI that lets you reverse unwise decisions - as long as you haven’t uncovered any new information. Then, once I’m satisfied I’ve found not just a good solution but the right one, I’ll pounce. Plopping down a final slipway, one that makes your empire burst into bountiful, platinum-tier planets along a chain reaction of contentment, is one of the most satisfying accomplishments in videogames. It’s like watching one of those videos full of things fitting perfectly into other things, or finding a fiddly checkmate. It is better than doing a Tetris, even an artfully engineered one with a saved-up long bit. I implore you to go ponder some orbs. Ollie: Slipways is incredibly elegant. Not just in its presentation but in the organic problems and solutions that arise as you expand your interplanetary empire. So many times throughout my various hour-long playthroughs, I’ve felt like I’ve slipwayed myself into a corner. I’d look at my tangled web of planets and their desperate cries for more water or bots or biomass, and I’d wonder at how in the world things went downhill so quickly, and how I could possibly prevent the total collapse of my once-promising economy. But in almost every case, the solution would start to present itself over the next few clicks. I’d send out a probe that would reveal a nearby planet with exactly the right set of imports and exports to resolve the crisis, or I’d research a technology that allowed me to demolish the useless planet that had been blocking that all-important slipway path between two far more important worlds. Slipways frequently tiptoes towards the line between challenge and frustration but never actually steps over. The solution may not always be in view right away, but rarely will there not be one waiting for you in a few turns’ time.