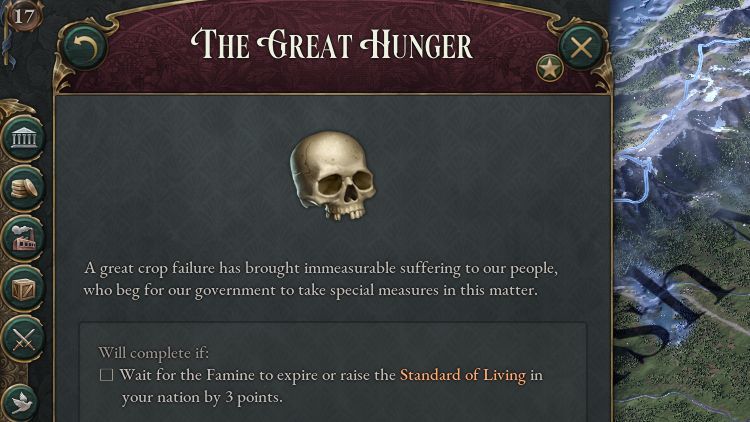

I’m trying to learn new languages, though, so it’s not an unwelcome challenge. The problem is that previewing Victoria 3 is quite an advanced level to dive in, the Paradox GSG equivalent of being a live translator for a UN summit when you’re only just about able to read the French version of The Famous Five. In a presentation before I and others were let loose on the better part of a week with the game, it was claimed that Victoria 3 is the best yet for onboarding newcomers, with a deep and detailed tutorial system. And to that I say: kinda. Luckily, the AI in Victoria 3 is so advanced it’s better at playing the game than I am. Victoria 3 simulates running a nation for a century, starting in 1836 (a tumultuous century, taking you up to just before the Second World War). I asked Nate Crowley (RPS in peace) for some tips for playing, and he went “Victoria 3? Ooh, that’s probably a bit much for me,” and since he likes Dwarf Fortress you can imagine how concerning I found that. “That one runs on Pops, doesn’t it?” he said. It does. Victoria 3 claims to be an impressive simulation of basically the entire population of Earth in its Pops system, keeping track of where people are and what they’re angry about all the time. There are farmers, labourers, machinists, shopkeepers, clerks, academics - a bunch of ’em, all falling into different classes and pressure groups, divided by political belief, religion, culture, and many other things. It’s both maxi and mini. You can zoom in from a flat map, where every country is an outline painted a different colour, and suddenly see the mountains and the clouds, migratory birds scudding across the sky. Even further and you can see the roads, trees, cities and towns. As you put in railways you can see it change the landscape, towns in regions with unrest start to raise literal red flags to signal support for revolution. It’s an impressive system, with a lot of tabs and levers to press and pull, but the UI is really readable and easy to use, even despite nesting tooltips being a thing. You’re also given a steer, if you need one, by a journal tracking some significant short-term goals (short-term here sometimes meaning “over the next three years”). There’s a lot of stuff to look at, but the trick seems to be in figuring out which bits you can ignore most of the time. I did play the tutorial, which explained all the basic elements of running a whole country (in this case Sweden), and it got me through the different parts of an economy and how to tinker with them: checking the output of your different rural and urban industries, not importing too much more than you export, and so on. It was going fine until the game set me the target of increasing Sweden’s GDP by 1.5 million. I could only get up to about 800k or so. I stalled on this goal for about four hours, which is quite a long time when you only have a hundred years to play with, and I realised it was because I don’t know how GDP works in real life. For all that Victoria 3 could tell me how Victoria 3 itself operates, the problem (if it is one) is that its simulation of global politics is complex enough that it’s also contending with a theoretical new player’s general knowledge. It’s not reasonable of me to expect the devs to provide a two hour video essay explaining things I don’t know about economics. I had a quick squiz through Google off my own bat, but I was burning daylight. So I thought, “Fuck it, let’s take over Denmark.” This was intended as a kind of LOL move, so that at least I’d have a wild anecdote to share with you if I achieved nothing else in the rest of the preview. War is a risky move in Victoria 3, because it can be expensive and demoralising. Surprisingly, however, I won my war very quickly. It was just something that happened while I continued running Sweden. War needs keeping an eye on, but if you have a strong-ish military before going in, and, crucially, all your target’s allies are indifferent or too far away to join in, your odds are okay. So a) the region of Denmark that had Copenhagen in it was now Sweden and b) the war super-charged my economy. The next pop-up in the tutorial said it was going to teach me the finer points of politics and diplomacy, which was pretty good timing. As well as a bunch of my smaller neighbours starting to eye me with deserved anxiety, I had also accidentally starved a bunch of my people. A lot of the Pops in Sweden were well below their expected standard of living, and were getting plenty mad about it. But starting and winning a war on a whim had both convinced me that wars are good, and that I could just embrace the Victoria 3 ethos of trying things and making mistakes, rather than searching for an objective measure of success. There are so many things to juggle that you have to keep your big clown unicycle of a nation moving at all times. Not having actions queued up is anathema to the game. Plus, sometimes you just want to welly a ball off in a random direction and see what happens. The next goal in the tutorial was to change the health system to one of socialised medicine, which would take quite a while (I played the tutorial for over ten hours and got, optimistically, about a quarter of the way through the century). Instead, I started thinking in countries, in the way Portal trains you to think in portals. I imported loads more wheat and invested in intensive farming methods in the more stable north of the country. I spent years suppressing the bloody Industrialists, who spent decades on the verge of revolution, and were a systematic thorn in my side. I also started bolstering my navy, in preparation for another war, and booted the church out of government, instantly giving it about 20% more legitimacy. As soon as my peace treaty with Denmark timed out, I took over the Northern chunk of Denmark. Everything’s coming up Sweden! I started the game again without the tutorial and came to the conclusion that running a nation is mostly about not failing but in a vaguely forward direction rather than actual success. I tried to industrialise too fast, and lost a big chunk of our nation’s money by chucking railways where they weren’t needed, so scaled back and started building more food stores and universities to increase the standard of living and literacy in the more urban areas I did have. I started researching pasteurisation and mechanised farming. I opened new trade routes to bring more fertiliser in, because, like a retiree growing tomatoes for the county fair, we could never have enough fertiliser. I wish I could tell you I engaged with some of the more figuratively difficult systems like colonialism and slavery to see what the deal was there, but I was simply not good enough at the game to explore it. What I did do one day was leave the game running on its own. I wanted to see how robust the Pops system was without any input from a human hand, so I booted up a game playing as France and went out. When I came back about five hours later, France’d had 40 pretty successful years without any input from me. Every time a group raised an issue, it timed out and the game picked the default option (e.g. in Sweden the bloody Industralists were always complaining about much land wasn’t being used for intensive farming), and it turned out absolutely fine. If you don’t steer active research into new technologies, people will work out new things by themselves, as people do. France appeared to have had and won a small war, their GDP was massive, and the only problem seemed to be an extremely low government legitimacy. On the one hand, this is a very good endorsement of Victoria 3’s Pops system. The AI is advanced enough that countries are basically huge cruise ships that you steer, dealing with queries about the potato salad stores or staffing levels while all the guests sort themselves out. You can’t fail because the ship would keep going without you. I came away extremely impressed by it all. On the other hand, it did make all my achievements with Sweden seem pretty hollow. It’s a blow to realise the game doesn’t really need you around. It’s more fun if you are, though.