Zak McKracken And The Alien Mindbenders is… it’s really terrible. Like, beyond belief awful. Oh no. The Lucasfilm Games adventure first came out for Commodore 64 in 1988, then for Atari ST - on which I first played it - in 1989. So I would have been 11 years old. I’m pretty sure I’ve never played it in the intervening 31 years. I’m not entirely sure why I entered this with so much confidence of being right. Betting my idiot child self against probably the world’s foremost expert on adventure games. Hey, I’m plucky!

Zak Mak, as I shall abbreviate it whether you like it or not, has such a fun premise. Aliens have secretly invaded the world, and are emitting some sort of tone through everyone’s telephones to cause a global stupidity epidemic. As I began the game, I so confidently thought to myself how I could write an introduction saying something like, “What more topical subject could it offer than observing a global trend toward frightening stupidity…” You know, rather than the confession I was morally obliged to replace it with. Yet it remains a great conceit! The titular Zak is a hack for a sleazy San Francisco tabloid, who professes a desire to no longer make up ludicrous stories and do some proper journalism. His boss bellows at him to shush and go chase a story about a two-headed squirrel somewhere in Seattle. So begins Zak’s globetrotting quest to… er… um… something something? What’s most striking - even before we get to the nonsensical puzzles, the impossible complexity of guessing where to go and what to do, and those godforsaken mazes - is just how incoherent the whole game is. Zak’s entire personality is that he writes bad headlines. That’s it. There’s no moment that endears you to him, or makes you take against him. He’s no one. Not least because the game makes the most extraordinary decision to not include a ’look at’ option in its collection of interactive verbs.

When a point-and-click adventure lets you ’look at’ everything in the world, it not only communicates information about those objects and views, but also the personality of the protagonist describing them. Does he find two-headed squirrels cute or irritating? Is he scared of darkness or intrigued by it? We never, ever find out here. And with that, we never find out about the world either! You pick up objects, you use objects, but you never learn about objects. The result is so distancing, so detached. And of course, every single opportunity to write a prompt, a nudge, or build a rationale for why you might use an object in a certain circumstance, is completely removed. It then exacerbates this by also not featuring a ’talk to’. And this is a game that not only of course features other people in the world, but three other characters to play as! With Zak and Annie on Earth, and Melissa and Leslie on Mars, some sort of interaction between them might make sense. Yet barely two sentences are exchanged between the four in the entire game. Oh, sorry, who are Annie, Melissa and Leslie? I can barely tell you. Annie works for some sort of society interested in ancient artefacts, and Melissa and Leslie are two coeds who had a dream of how to build a spaceship that would take them to Mars. That’s it. That’s literally all I know about them having finished the game.

But now we must get to those nonsensical puzzles and the impossible complexity. On paper, Zak Mak sounds like quite the prospect. There are locations all around the world, flown to by plane via a network of airports. Zak and Annie can travel to Cairo, Lima, Mexico, Kinshasa, Miami, London, Seattle, and Katmandu! What’s awaiting them in each location?! The game doesn’t feel the need to say. Who should go to each? Nope, nothing. So travel between them is free and easy? Of course not! You have to pay for every plane ticket, so guessing where to go next becomes expensive, and raising cash is tiresome. There are ways - selling bent butterknifes, finding an alien device that controls the lottery, etc, but what a ballache. It’s too long since I understood how factorials work, so someone else can work out the permutations of who can go where with whom while holding what. But the short version is: I followed a walkthrough. Because bollocks to what this game was asking of me. Not least because, whenever I got anywhere, it involved ‘solving’ more of its deranged puzzles. Stuck in the sea, and despite having built an adequate diving kit from inventory items, are told that for no given reason you can’t swim deep enough? Of course you blow the kazoo to attract a dolphin! I mean, aren’t we all told: “If you fall out of a plane into the sea, blow your kazoo for dolphin help, especially when the only sign of sealife is what appears to be a shark fin in the background.” I mean, whose grandmother didn’t tell them that at least once?

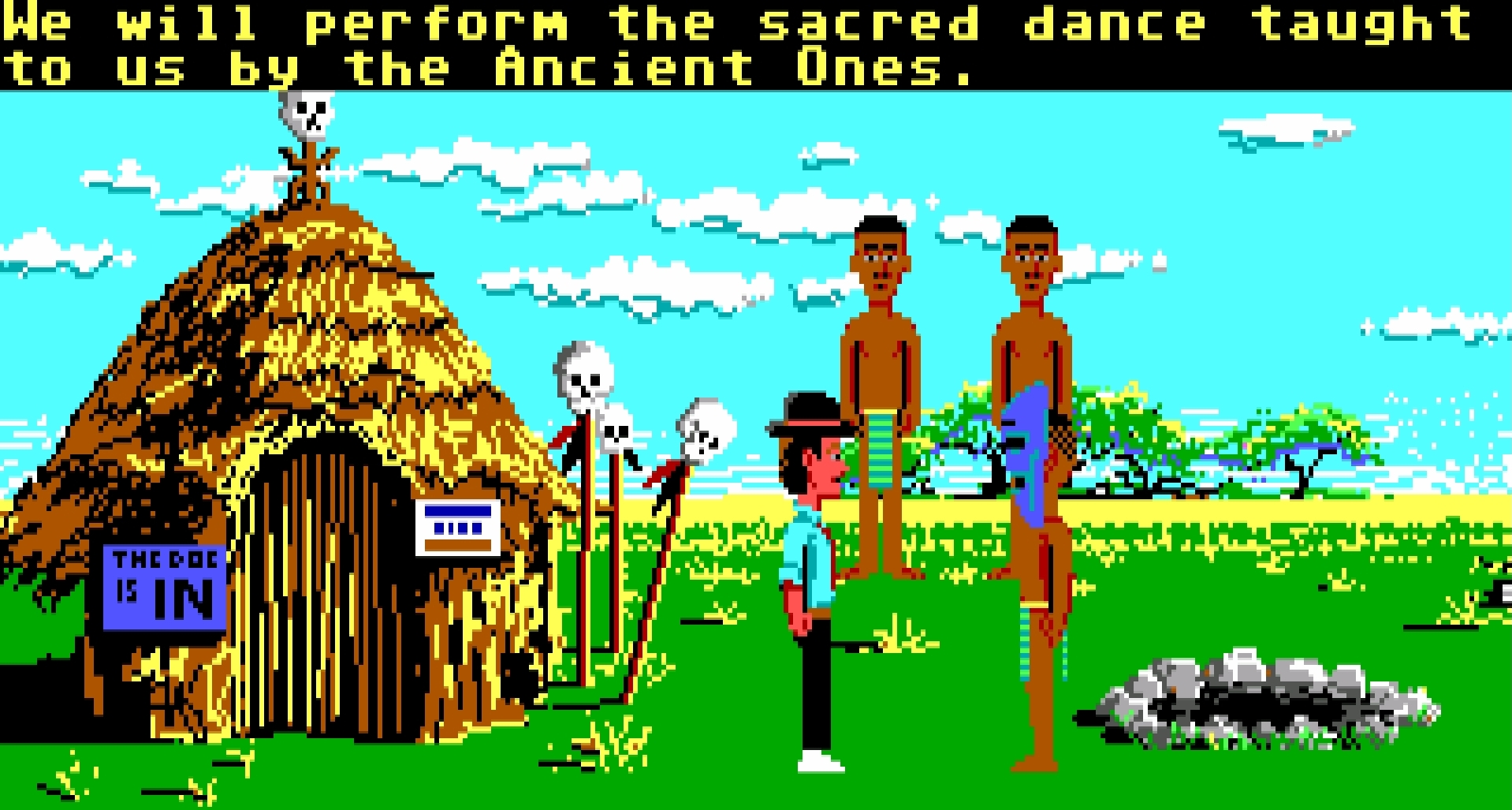

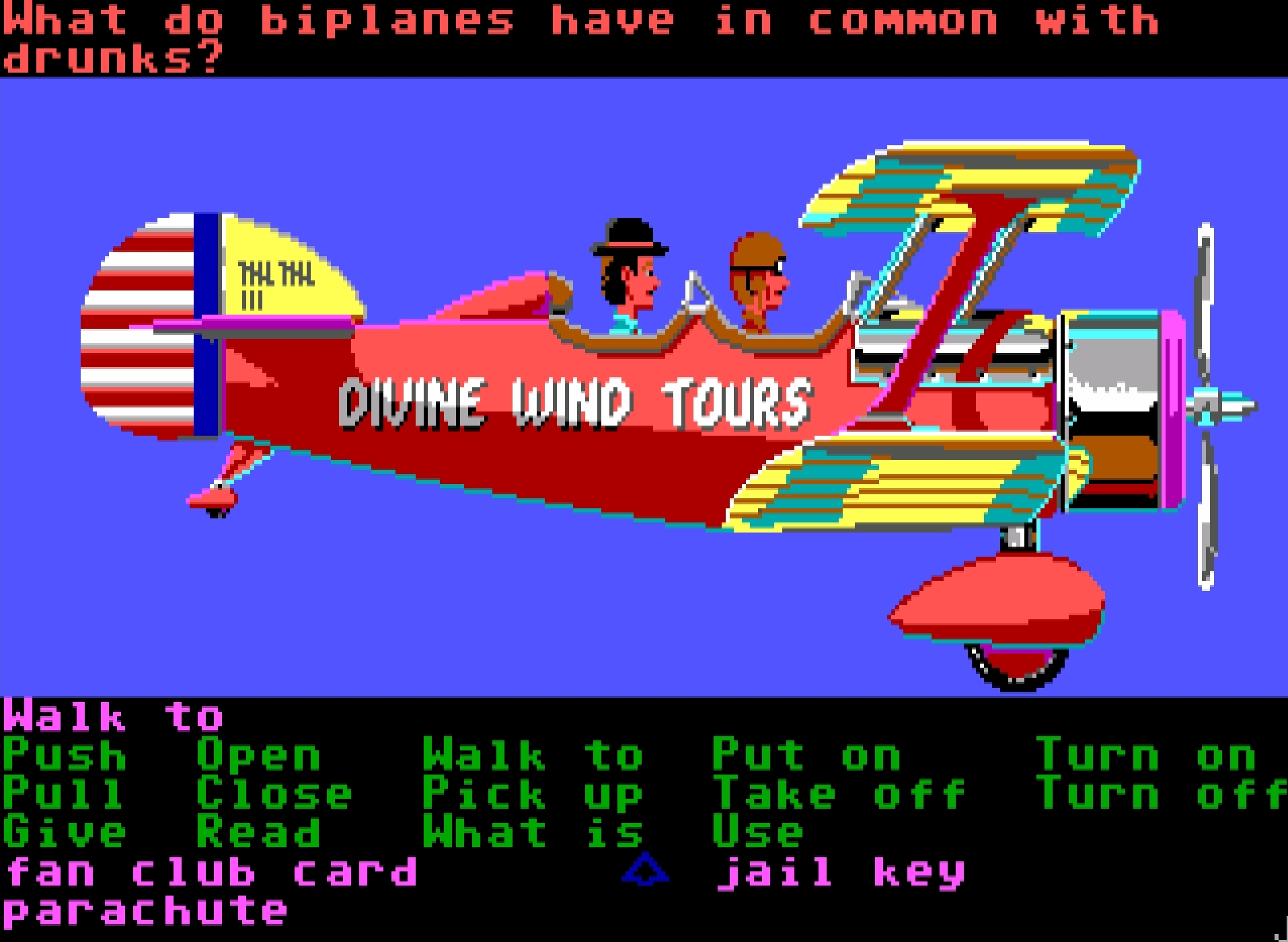

It gets worse. There are clues given to you once and once only, but spectacularly, without any context. So when you are treated to the uncomfortably 1980s sequence set in the Kinshasa desert, with tribesmen dancing for you, you are to divine that the order in which they bob up and down is in fact the order in which you press some buttons in a temple on Mars. I mean, naturally! Don’t psychically predict this utterly dissociated pattern, and fail to notice the bobbing order the first time, and… oh, that was the only time. They won’t do it again. Nor indeed will the biplane pilot on the alien ship repeat the colour code for teleporting to where his plane used to be, such that you can fall into the sea… There aren’t enough ellipses to communicate this game’s detachment from coherence. And then, yes, dear God the mazes. It was like there was some sort of collective insanity in the game development community of the late ’80s, where absolutely everyone thought they had to have a randomised or impossible-to-map sequence in their game, where players were left forced to wander aimlessly at great length until they stumbled upon the correct location. A horrible hangover from text adventures and their inevitable forest, they were also a feature in far too many Sierra graphic adventures, but no one ever did it worse than this. Here there are multiple mazes, both randomised and impossible-to-map, and each time you’re required to go through them twice, both in and out, and sometimes multiple times with multiple characters! Aaaarrggghhh!

I love that Zak Mak is a game so bad that even those dedicated enough to write walkthroughs for it can’t stand it. I particularly enjoyed this one, published on a Zak McKracken fan site. It contains the line, In the end I stopped trying at all, since that rewarded me nothing, and just blandly followed a walkthrough for the most part. It’s not as if the game offered fun responses to incorrect ideas - it doesn’t offer fun responses at all. And since there’s no direction, no sense to your next move, just random stumbling, I really couldn’t stand the idea.

I can only assume my 11-year-old self was following a walkthrough in a magazine at the time, such that I could form happy memories of wearing silly Groucho glasses/moustaches to pass as an alien. And, to be fair, there’s one good puzzle in the game: flooding the aeroplane bathroom, then microwaving an egg, in order to be able to steal an oxygen tank. And I say a “good” puzzle, but it also involves somehow knowing that one and only one of the chair cushions can be picked up, to reveal the absolutely crucial lighter, without which the rest of the game will be impossible. (Seriously, try picking up another empty seat cushion and you get a generic “I can’t do that” response. That’s the degree to which they go to make this impossibly obscure.) This just doesn’t bear a single quality that made Lucasfilm/LucasArts the greatest adventure developers of all time. Despite releasing after Maniac Mansion, Zak Mak is completely devoid of their magic, not a glimmer of the sharp writing, excellent puzzle design, nor characterisation, that made their games so deeply adored. Part of this might be ascribed to the odd development path it took. Its project lead, David Fox, apparently wanted to make it a serious game exploring new-age spiritualism and accompanying extraterrestrial gibberish. Then Ron Gilbert persuaded him to add some humour. The result is a guided tour of UFO-loon worldwide hotspots + wacky glasses, and this collision of intent and requirements created such a uniquely horrible game.

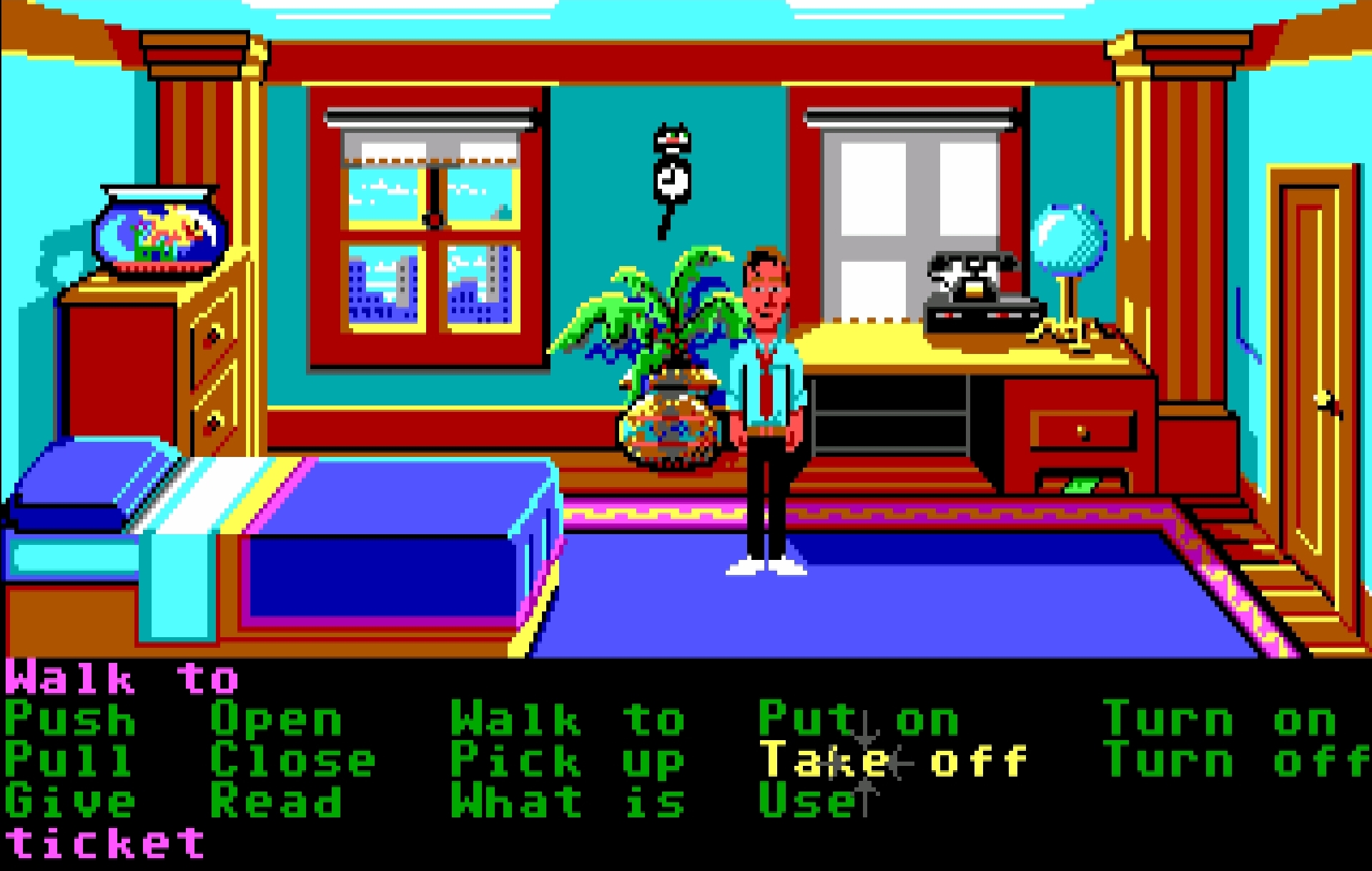

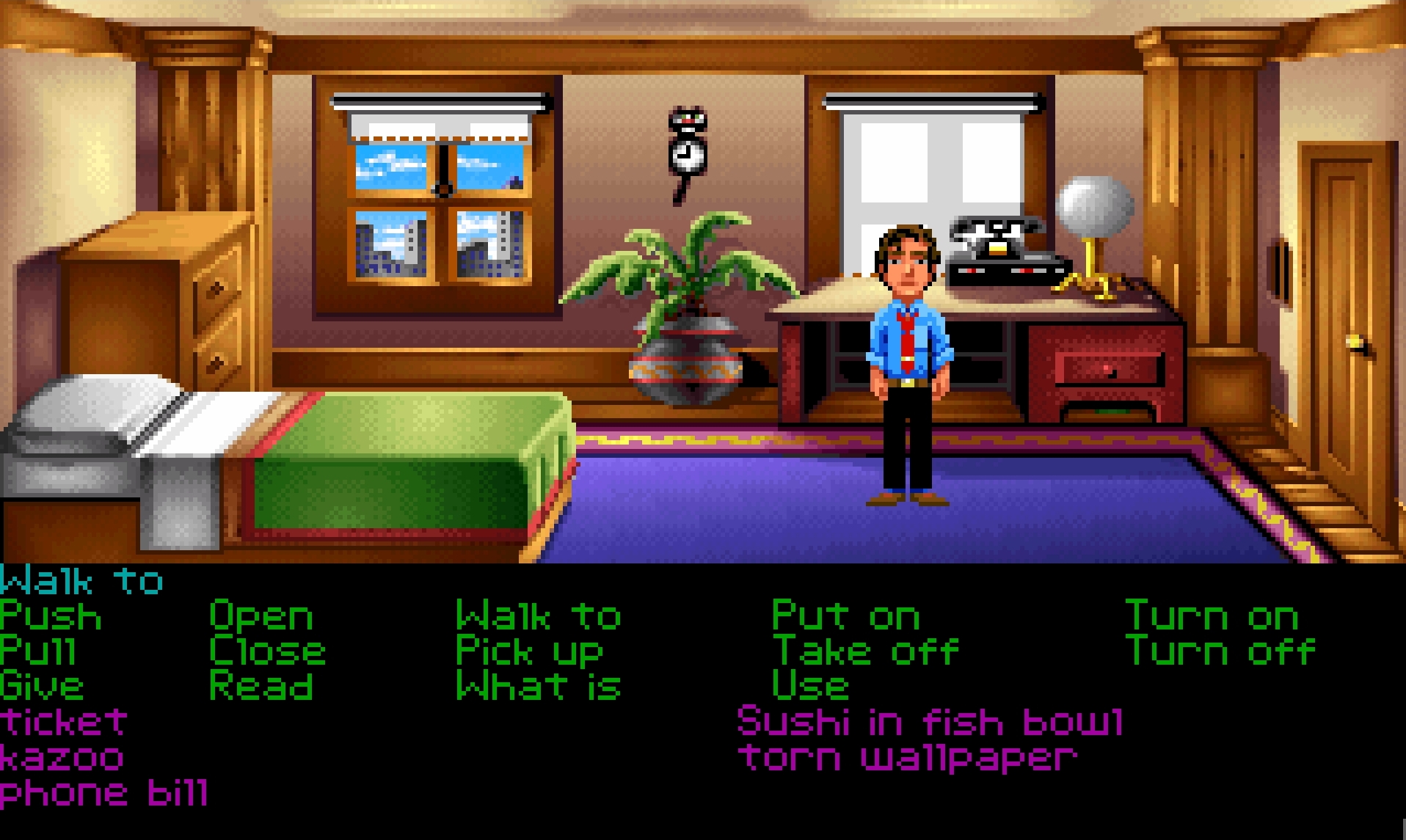

I should add that there are two ways to play today. The Steam and GOG releases include a patched version of a formerly Japanese-only 1990 CD-ROM build, with 256 colours and non-bleep-bloop music. I tried it, but it just felt… wrong? I dunno. I wanted to play the original EGA version, as I recognised it, I suppose. The pseudo-VGA version offers nothing more than the redrawn art and music, no other improvements, sadly. And even more sadly, there’s no neat way to switch between the two, rather each running completely separately, with their own sets of savegames. The greatest flaw that cuts through every element is the lack of dialogue. There’s no communication, between the characters and their world, nor the game and the player, and it’s disastrous. That the puzzles, characters, and plot are all awful, somewhat doesn’t help.

So yeah, Richard. FINE. You were right, I was wrong. Gosh, really horribly wrong. This is atrocious. Can I still play Zak McKracken And The Alien Mindbenders? You can. It’s on Steam and GOG, running in an in-built SCUMMVM, and works right out of the digibox. Should I still play Zak McKracken And The Alien Mindbenders? Good grief no.